Bike to Work Day as an opportunity to assess the state of bicycle planning: Part 2, big picture planning

-- Bike to Work Day as an opportunity to assess the state of bicycle planning: Part 1, leveraging Bike Month

-- Bike to Work Day as an opportunity to assess the state of bicycle planning: Part 2, big picture planning

-- Part 3 to come: better bike planning in the DC area

=======

Although, federal transportation planning incorporates the bicycle as a mode, and offers plenty of technical assistance and guidance, the US lacks a national bicycle plan and strategy.

-- "What should a US national bike strategy plan look like?, 2014

-- "Are developers missing the point on eliminating parking minimums?: it's to promote sustainable transportation modes," 2012

-- "More bikes: elements of a Bicycle Friendly Community," 2015

Countries like Germany and Switzerland have such plans. Here's Denmark's, Denmark - on your bike! The national bicycle strategy.

-- Cycling Embassy of Denmark

-- Bicycle information portal, Federal Ministry for Transportation and Digital Infrastructure, Germany

A diagram from an old German bicycle plan helped clue me into thinking about bicycle mobility as a system.

Bicycle Traffic as a system, diagram, German National Bicycle Plan, 2002-2012

States and provinces around the world also can have great plans. A couple standouts include Quebec, Canada and Victoria State, Australia.

1. Plan for bicycle-based transportation as an integrated system.

2. Have a national bike plan.

According to a Bicycle Dutch post on Delft, "1979 Delft cycle plan," Delft was one of the first communities to figure out that a key element of significantly increased bicycle ridership was the provision of a more complete "network" of connections that would make bicycling for transportation an efficient choice. The focus wasn't on making a system separate from roads, which is how people think of the Dutch approach today, but on eliminating gaps that hindered people from making "complete trips" from and to various points. From the post:

After the experiments in Tilburg and The Hague in the 1970s, where they built one very good (but also very expensive) cycle route, that had mixed results but didn’t lead to more cycling overall, Delft took a different and innovative approach. Delft wanted to improve the city’s existing cycle network, which had a lot of missing links. …3. Focus on creating a complete bicycle route network within towns, cities, counties, and metropolitan areas, not exclusively on creating a separated network.

“We were determined to get a good network of cycle routes, not necessarily all on protected cycle paths, because we knew we couldn’t afford that.” André tells me, “And we already had good experiences with traffic calming of roads and streets.” It may be good to realise that there was no ‘zero’ situation in Delft. The presumption was, there were parts of a network, but with many missing links. The network of the plan already existed for about 75% (this includes traffic calmed streets and cycling infrastructure on distributer roads). The modal share for cycling before the plan was already 38%. …

To investigate what the people in Delft really wanted, the Ministry of Public Works hired a German sociologist and survey expert. This caused quite a commotion in the world of traffic experts and engineers at the time. Werner Brög from Socialdata in Munich, investigated 4,700 households (Delft was a city of about 80,000 inhabitants at the time). It was an in-depth investigation. People were visited at home and they weren’t just asked how they travelled where, they were specifically asked for their constraints, the reasons why they didn’t cycle to supermarket X for instance. The answers were very concrete: “because intersection Y doesn’t feel safe”, or “because canal Z forces me to make a detour of that many metres”. The response of the survey, 72%, was very high and helped the city to identify the most important physical, financial and mental barriers to cycling in the city.

4. At the metropolitan scale, there are a number of developing examples. One is the NCC Pathway Network in Ottawa City, Ontario, organized by the capital area planning organization. Others that come to mind are fortunate to enjoy foundation support. In Akron, the Knight Foundation has been a key funder for the iTowpath bicycle trail project ("How improvements to Akron’s Towpath will better connect residents to the city," Knight Foundation; "Knight Foundation awards $500k grant for Towpath," Cleveland Plain Dealer), providing intra-city bike connections to the regionally-serving Ohio & Erie Canalway Trail.

-- planning process brochure

-- explanatory brochure

In Philadelphia, the Circuit Trail Network initiative enjoys the support of key foundations, especially the William Penn Foundation, which provide more than $8 million in a single grant (The Region’s Trail Network, The Circuit, Gets Major Boost," WPF).

Roughly half the funding for the Indianapolis Cultural Trail came from the Central Indiana Community Foundation, and a lead gift of $15 million from Eugene and Marilyn Glick.

Although separated networks do help quite a bit.

Although separated networks do help quite a bit.5. Metropolitan bicycle transportation planning should also include the provision of facilities such as cross-jurisdictional secure parking networks, maps (printed and digital), signage, air and repair equipment, etc.

Los Angeles County Metro's developing system of Bike Mobility Hubs is a good example of providing hub facilities at transit stations. Victoria State's Parkiteer bicycle parking system is an example of a system of more than 100 parking nodes all using the same access system. Transit stations in the Netherlands, Denmark, and the UK often have great bicycle parking accommodations, etc.

6. Focus systematically on meeting the needs of all demographics, not just specific initiatives for women, African-Americans, etc.

See "Eight "mutual assistance programs" that can build support for biking as transportation on the part of low income communities."

7. Focus on providing direct assistance to people in making the switch to bicycling as a primary transportation mode.

Transportation agencies are great at building infrastructure, providing maps, etc., but only the most information-driven people will adopt bicycling as a result of "objective reasoning." This is one of the biggest gaps in bicycle planning. By contrast, many communities in the UK have programs where people can use a bike with helmet and lock for up to a month for a low fee (or free) to test biking for transportation without having to first buy a bike.

8. Adopt more innovative approaches for bicycle planning and presentation.

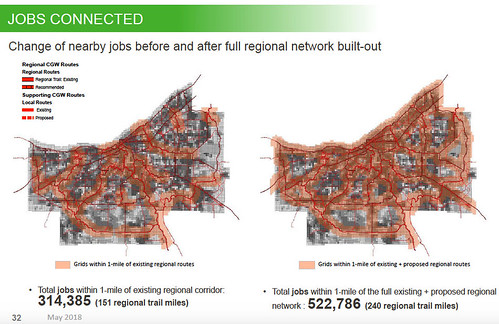

A few months ago, I came across the bicycle planning process for Cuyahoga County, Ohio, called Cuyahoga Greenways. The county plan proposes 240 miles of new trails, 151 miles of trails focused on eliminating gaps in the current system, and 571 miles of "local," supporting trails and multi-use paths providing connections to an expanded regional system.

-- presentation

It also laid out the proposals in terms of providing access to jobs and a larger proportion of the county's population, along with economic development elements, which I thought was pretty innovative. They also promote the health aspect of bicycling, although that isn't a new approach (although health is one of the primary reasons I cycle).

Note that Cuyahoga County also co-sponsors a biennial Greater Cleveland Trails and Greenways Conference, which is this year, on Thursday May 31st. (Oops, the previous Bike Month post should mention holding an annual conference that month.

========

9. Institute national requirements for lights including turn signals, on OEM bikes made for transportation use (hybrids, etc., not mountain and racing bikes). Currently, the Consumer Product Safety Commission either is forbidden from or chooses not to making such regulations.

Labels: bicycle and pedestrian planning, civic engagement, protest and advocacy, sustainable mobility platform, sustainable transportation, urban design/placemaking

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home