The Washington Post reports ("D.C. pledged to cut traffic fatalities by 2024. Deaths are up, and now the program is under audit") that advocates are complaining that DC's traffic safety initiative, Vision Zero, is ineffective as the number of traffic safety deaths has increased since the program started. In NYC, Mayor De Blasio faces similar complaints ("Things were looking up for Bill de Blasio. Then crises started piling up," Politico).

Thinking about this, one of the problems in getting a grip on the problem is that comparatively speaking, the number of traffic-related deaths in DC is relatively low, and even the same can be said for NYC, given its population.

Here are 11 points:

1. How to measure and benchmark traffic deaths? Because traffic-related deaths in cities like DC are comparatively low, I've found it difficult to get a handle on how to think about this.

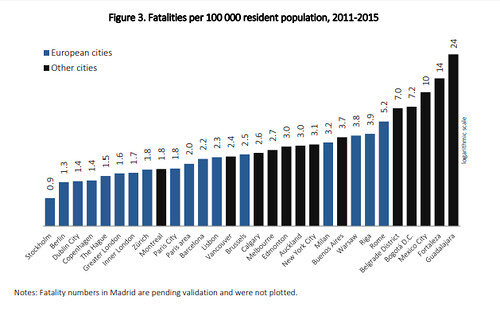

This blog entry, "First global benchmark for road safety in cities published by International Transport Forum," calls our attention to the metric promoted by the ITF, fatalities per 100,000 residents.

They used the measure "deaths per 100,000 residents." Stockholm had the fewest deaths on that score, 0.9 per 100,000, while Montreal had 1.8.

But with 700,000 residents, that means that DC's fatality rate is 4.28, almost five times higher than Stockholm, which has a population about 25% larger than DC, or 952,000 residents. The study recognizes that better measures, including daytime population numbers--nonresident workers and visitors--are necessary to get a better handle on what the data means.

DC has a high daytime population, but so do most of the other comparison cities. So now I see, comparatively speaking, DC's road-related fatality rate is pretty high.

The study finds that in cities, walking and cycling death rates are lower compared to countries as a whole, and within metropolitan areas, center cities are safer for vulnerable road users. Interestingly, the risk to men is about double that of women. Younger and older age cohorts are more vulnerable as well.

The report, Safer City Streets: Global Benchmarking for Urban Road Safety, makes some important recommendations.

2. The issues are unchanging. Basically what I wrote about this issue last year is still completely relevant, pretty much explains what's going on.

3. Government has a bias for inaction*. A big issue is that transportation agencies (and government agencies more generally), even very good ones like NYCDOT, aren't always that proactive, and tend to not have "a sense of urgency" when it comes to action.

Janette Sadik-Khan was NYC Commissioner of Transportation under Mayor Bloomberg, who was committed to sustainable mobility.It varies depending on the mayor. It's fair to say that in NYC Mayor De Blasio cares a lot less about this than former Mayor Bloomberg ("A Playbook on the Politics of Better Streets," Bloomberg), and in DC, most elected officials are from "the outer city" where the automobile remains dominant ("DC as a suburban agenda dominated city," 2013).

That's why too often, improvements are implemented after someone dies rather than systematically addressing problems beforehand ("Salt Lake City paints crosswalk where children were struck on way to school," Salt Lake Tribune).

A key point in the iterative improvement of my writings on Vision Zero is focusing initiatives in terms of the "6 E's" of sustainable mobility planning ("Updating Vision Zero approaches," 2016).

One of the reasons for failures in improvement resulting from Vision Zero "initiatives" is the lack of a systematic approach.

* A bias for inaction is a riff on the "bias for action" element of forward-looking corporations as discussed in the book The Search For Excellence.("Putting a Bias for Action into Planning Agency Management: A Practitioner's Perspective," Public Administration Review, 1986).

4. Planning for mode versus planning for place and livability. More recently, I wrote a piece, "Planning for place/urban design/neighborhoods versus planning for transportation modes: new 17th Street NW bike lanes | Walkable community planning versus "pedestrian" planning," making the point that there is a difference between planning for sustainable modes like walking or biking, versus planning an environment that is pro-walking, pro-biking, and pro-transit from a sustainable mobility standpoint more generally ("Extending the "Signature Streets" concept to "Signature Streets and Spaces"" "50 Reasons Why Everyone Should Want More Walkable Streets: from the Arup report, Cities Alive – Towards a walking world," "Further updates to the Sustainable Mobility Platform Framework").

Just focusing "on walking" or "biking" or "transit" is too limiting. Transportation agencies need to plan for "urbanity", "livability, "placemaking," and "quality of life."

A good example is how applying Safe Routes to School approaches have broader benefits for the neighborhoods where the school is located.

-- School Walk and Bike Routes: A Guide for Planning and Improving Walk and Bike to School Options for Students, Washington State DOT

5. Not treating the road system as a network. I've come to understand that looking at individual elements of the transportation infrastructure rather than the network is a problem. Often there are streets referred to as "Boulevards of Death" ("'Boulevards of death': why pedestrian road fatalities are surging in the US," Guardian, "A more radical approach to "Vision Zero" is needed: reconstructing streets out of different materials to reduce speeds," 2019, "Pedestrian fatalities and street redesign," 2019). That's because the failures are systematic and result from urban design.

While it's not uncommon to at least mention this with biking ("1979 Delft cycling master plan," Bicycle Dutch blog) it's rare for traffic engineers to consider major streets as a sub-network element and consider intersections as a whole ("Barnes Dance Intersections as possible "solutions" to Wisconsin & M, 14th and U intersections," 2014).

While the Smart Transportation Guidebook doesn't call for treating streets as systems and networks, it does provide a great framework for thinking about some of these issues in terms of:

- land use context

- whether roads are local or regionally serving

- desired operating speed of traffic, and

- roadway and roadside characteristics in terms of (1), (2) and (3)

6. Traffic deaths can be broadly categorized into three segments. In reading the Politico article, it occurred to me that from "a big data" perspective, in center cities you can segment traffic-related deaths in three broad categories:

- drivers generally unfamiliar with driving in cities, in "mixed traffic," that is alongside pedestrians, bicyclists, and transit users, where pedestrians, bicyclists, and transit users make up a preponderance of traffic. Such drivers don't think of non-automobiles as being legitimate users of the right of way. As a bicyclist in DC, a majority of the incidents I had with motor vehicles had non-DC license plates.

- traffic engineering and design that promotes automobility over pedestrians, bicyclists and transit users, when those users make up a preponderance or majority of traffic. This can be as simple as pedestrian timing signals that don't provide enough time to get across the street, and putting bicyclists and motor vehicles in conflict by the way roads are designed.,

- reckless driving by motor vehicle operators.

But typically this isn't a process with much public involvement, and because of the bias of inaction, it can take a long time to make change. So open it up, make this a function of the Bicycle and Pedestrian Committee.

11. Mapping pedestrian, bicycle, transit and car accidents. Systematic collection and publication of accident data is key to doing the kind of analysis where you can make extraordinary improvements through urban design changes (blog entry, 2009)..

If you go through DC crash statistics, I think it's safe to say in the large majority alcohol is involved.

ReplyDeleteAlso, it's mostly black drivers. Nobody wants to touch on that.

So in terms of your analysis, the overwhelming majority of DC traffic deaths in reckless driving, not road conditions.

That's my beef with Vision Zero in DC; it doesn't really address the issue. The stats do hide the issue, as DC has a much smaller part of a much larger metro area.

The issue in DC isn't pedestrian or biker fatalities - or even driver fatalities . Driving in DC fro the most part won't kill you. We don't have many opportunities to speed, drive down one way roads, and do the stuff that will kill people on the road.

Where DC is really bad is the quality of the driving.

https://www.washingtonpost.com/transportation/2019/06/26/drivers-these-two-cities-are-worst-report-says/

And baltimore ranks highly there as well.

So there's a lot of danger on the road, but it isn't going to get you killed.

I'm terrified to ge ta new car because the number of people I've known in DC who've gotten one and had it crashed into within six months is very high

My car has been hit four times while parked.

The vision zero push for 20 or 15 is ridiculous and is just contributing to a massive culture of non-enforcement. We now regularly have dirt bite drag races on U st with zero enforcement.

Red lights appear very optional right now, what is good for bikes is just as good for cars. Likewise one way street.

Will this stuff kill you -- no. Is it dangerous -- absolutely.

I always thought that the 15mph was dumb. I would really like to see streets re-engineered with materials like Belgian block.

ReplyDeleteAnd that many of the city's streets function like bike boulevards or small parkways, so you're absolutely right that for the most part, people don't speed.

If I were to do a further breakdown it would probably be:

- unfamiliarity

- design

- specific conflicts primarily at intersections and crosswalks

- reckless driving including subcategories of alcohol and/or drug impairment and

- crime (like the two girls near Nationals Park, technically that was a traffic-related death I would think)

WRT quality of driving, using big data to figure out the indicators, force driver re-education and other steps as needed.

WRT "small accidents", yes that was a problem on our street. Cars getting crashed into was more rare, definitely many lost drivers side mirrors.

============

BUT the other thing to study are the collisions/crashes that don't result in death, but in injury. That shouldn't be ignored.

I once saw a bicyclist get hit. I can't remember the specifics now, if she had the right of way and was hit by a left turning car (tax). Or maybe she was on the street that the car turned onto (it was at Florida and 13th Street NW, at the bottom of the hill, I was going west on 13th).

She was screaming. She probably was injured.

I don't know if you're old enough... but when I was a child, there were lots of public safety ads on tv, with the tagline "most accidents occur within 25 miles of home."

ReplyDeleteIt took me years to realize that's because most people do the bulk of their driving within 25 miles of home.

Some demographics and categorization would go a long way.

In this piece, I didn't directly cite any of my previous criticisms of the DDOT dashboard, which on accidents provides zero actionable information.

======

home the downsizing trip wasn't problematic, not spurred by "bad stuff" but just "moving" (e.g., when my parents moved to Florida, had to get my stuff and my brother brought me my bike from high school, which led me to start biking in DC).

tax = taxi

ReplyDeleteThe street lawlessness you describe is scary. I've always thought parking enforcement should also be deputies wrt traffic enforcement.

ReplyDeleteTwo other points:

ReplyDelete1. Again, not something you're going to pay attention to, but there are an increasing number of safety technologies being put in. Will they increase or decrease the numbers?

The old joke is the best safety technology is a large spike 3" from you head while driving. I'm not convinced the new stuff will held and I think the insurance data is bearing that out. That said is changing. My dad has the orginial 'blind spot' rear view mirror which could not see cyclist, drove a car this weekend and is did bit up a scooter rider (higer) but not cyclists.

2. One thing we have had in the past 10 years is Uber/ridesharing -- and no question they've been taking drunk drivers off the road. Is that showing up in urban deriving statics -- probably not. Again drunk driving is far safer than people realize*, 1/2 the deaths are essentially suicides** but you'd think we would be seeing more reductions in deaths.

* I'm sure than 90% of road deaths in DC involve alcohol (perhaps not drunk) but for an individual driving drunk might double the chance of a crash (non-fatal) over a lifetime. Sweden/Scandis have come down very hard on drink driving although less criminalization than the US. Can't wait for the SJW to pick up the racial component in DWI laws.

** Drunk young men driving over 75 on one lane roads at night with no seatbelts and crashing into a stationary object not another car.

There was an editorial in the wsj about the value of ride hailing in reducing drunk driving.

ReplyDeletehttps://www.wsj.com/articles/how-uber-and-lyft-can-save-lives-national-bureau-of-economic-research-study-11627597079

It says the deaths are cut by 4%. At the scale if a city or county that's not a lot.

2. Years ago in the mid 1990s went to a wake in exurban Maryland. A person in the car commented on the wind-y roads, saying "how could you drive home drunk, living here?

3. Crime is crime. I think we've discussed what I think of as political nullification, that since some police do bad things, this negates the criminality of criminal/anti social behavior.

Like your talk about increased breaking if traffic laws, the reality is that there is a thin line between order and disorder and a lot of it comes down to people dutifully following the rules. If you give in on little stuff, it contributes to worse stuff. The Moynihan argument...

I started reading Bratton's latest book a few weeks ago although I have to go back to it. While I argue under Giuliani the police department went to zero tolerance policing which is not the same as broken windows, Bratton's description of his taking over the transit police in 1990 makes you understand why BW was key. The subway system leaders understood that if the fixed the cars and operations it wouldn't matter if the stations and trains continued to be overrun by homelessness, graffiti and general disorder.

https://www.washingtonpost.com/local/public-safety/fatal-crash-girl-bicycle-washington/2021/09/14/67d4e70c-1568-11ec-a5e5-ceecb895922f_story.html

ReplyDeleteWrt my adoption of the Idaho Stop, the whole point is to not run signs and lights if there is oncoming traffic. It's not a license to create mayhem and conflict.

ReplyDelete"Driver from out of town, unfamiliar with the city."

ReplyDeleteA child on a bike was struck in a D.C. crosswalk — again

https://www.washingtonpost.com/local/child-bike-hit-crosswalk-dc/2021/09/29/b5128b14-2152-11ec-9309-b743b79abc59_story.html

Not DC but still relevant.

ReplyDeletehttps://www.charlotteobserver.com/news/local/crime/article253207173.html

https://www.bostonglobe.com/2021/11/17/metro/nobody-stops-petition-seeks-push-button-traffic-light-near-memorial-spaulding-school/

ReplyDelete"‘Nobody stops’: Petition seeks push-button traffic light near Memorial Spaulding School"

In Newton, Massachusetts. There have been 8 collisions at this intersection in 5 years.

Yes, it seems like a prime candidate for a stop light.

12/29/2021

ReplyDeleteThere is an article in the Post featuring CM Mary Cheh, lamenting that reckless driving is the cause of many accidents, and that the tools that exist aren't helpful at reducing the problem. Which of course is mentioned in this blog entry.

"D.C. finds enforcement shortcomings as it grapples with rise in reckless driving"

https://www.washingtonpost.com/transportation/2021/12/28/dc-traffic-enforcement-ticket-amnesty/

FWIW, I wrote about another DC initiative on this in early 2020, a social marketing initiative to send messages to bad drivers.

http://urbanplacesandspaces.blogspot.com/2020/12/social-marketing-and-aberrant-driving.html

The issue isn't that they don't know what they are doing. They do know, and they don't care.

I came across this article too, when trying to find the other one.

"Reckless driving is causing a spike in traffic fatalities. We must do better."

https://www.washingtonpost.com/opinions/2021/11/06/reckless-driving-is-causing-spike-traffic-fatalities-we-must-do-better/

This article on lessons from the Canadian trucker protest in Ottawa, Ontario makes interesting points about institutional failure.

ReplyDelete"What the trucker convoys taught us about our institutions and right-wing extremists."

https://www.washingtonpost.com/opinions/2022/03/07/trucker-protest-peoples-convoy-ottawa-canada-lessons/

He describes issues between the city, province, and federal government, calling it "Coordination gaps and slow reactions."

That's more polite than "bias for inaction."

On "Coordination gaps and slow reactions" he cites two Globe & Mail articles:

https://www.theglobeandmail.com/politics/article-federal-government-urges-ottawa-police-to-take-control-of-convoy/

https://www.theglobeandmail.com/opinion/article-mark-carney-end-freedom-convoy-ottawa-state-of-emergency/

Both make the point that authorities didn't take the protest seriously, which hampered their ability to deal with it.

I was struck by the parallel to the 1/6 insurrection at the US Capitol.

Despite violence at pro-Trump protests in DC in December, the Capitol Police (and to some extend DC's local police department) did not prepare as if there could be violence.

D.C. says it has ‘fallen short’ of goal to end traffic deaths

ReplyDeletehttps://www.washingtonpost.com/transportation/2022/10/27/dc-vision-zero-traffic-deaths/

I didn't realize there was reporting on where a majority of the deaths occur, in Wards 7 and 8, the "poor" wards, which dovetails on discussion in comments about aggressive driving. But also the presence of DC 295 which is designed in ways that promote accidents.

https://www.washingtonpost.com/transportation/2022/02/23/dc-traffic-deaths-highest-record/?itid=lk_inline_manual_12

D.C. traffic deaths at 14-year high with low-income areas hardest hit

The toll has fallen disproportionately on the city’s two poorest wards, which recorded half of its road deaths in recent years

New Vision Zero website

https://visionzero.dc.gov/

I will say they seem to have addressed some of my complaints in the past on this, that the DDOT "dashboard" didn't provide actionable information. They actually have "crash analysis memos" online, which are what should be used to identify areas of opportunity for structural improvements.

Although the memos are cryptic. E.g. the one on the crash at Massachusetts Avenue that I wrote about ()

doesn't say that the operator of the striking vehicle was driving recklessly, no recommendations about identifying bad drivers systematically.

The point about making separated bicycling infrastructure was indirect. Safety would be improved by moving bikes away from cars.

I wrote about this incident too.

https://ddot.dc.gov/sites/default/files/dc/sites/ddot/D22-21%2021st%20and%20I%20St%20NW.pdf

The memo doesn't discuss the fact that the cyclist "rode into" the situation instead of avoiding it.

https://urbanplacesandspaces.blogspot.com/2022/08/bicyclist-deaths-bicycle-safety.html

Before he was the mayor of Hoboken, New Jersey, Ravi Bhalla was just a local resident struggling to cross the city’s main street with his two young children because it lacked pedestrian crossing signals. While he was on the city council, a woman was killed crossing that same street. So when Bhalla took office in 2018, he made road safety a priority and kicked off Hoboken’s commitment to Vision Zero.

ReplyDeleteFrom redesigning intersections to installing bike lanes and reducing speed limits, the city has transformed its streets. And since 2017, it’s reported zero pedestrian fatalities. But Bhalla isn’t declaring victory just yet. In the latest in a series of conversations with mayors, he spoke with Sarah Holder about his longer-term goals, and the challenges he’s come across in implementing the changes needed to meet them.

The New Jersey Mayor With a Plan to End Traffic Deaths

https://www.bloomberg.com/news/features/2023-11-20/this-new-jersey-mayor-ended-traffic-deaths-with-a-vision-zero-plan

https://www.bloomberg.com/news/features/2022-12-28/it-s-been-a-deadly-year-on-us-roads-except-in-this-city

ReplyDeletehttps://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2022-11-25/the-us-cities-where-vision-zero-traffic-safety-fixes-are-working

How 'daylighting' helped Hoboken make its streets safer—and how other cities can follow its lead

ReplyDeletehttps://www.fastcompany.com/91055859/how-daylighting-helped-hoboken-make-its-streets-safer-and-how-other-cities-can-follow-its-lead