Our "friends" the Lerners: More about constructing buildings vs. creating places

![WrigleyRight_Pregame_LR[1].jpg](http://static.flickr.com/75/166114084_9b8a2c3cfe_m.jpg) Chicago's Wrigley Field and houses across the street in "Wrigleyville." Photo by Sandy Sorlien.

Chicago's Wrigley Field and houses across the street in "Wrigleyville." Photo by Sandy Sorlien.Speaking about the necessity of urban design as the ultimate guiding element for the Comprehensive Plan revision, I've been meaning to write about the latest whining from the Lerner baseball group, as reflected in this article from the Sunday Washington Post, "Battle Brews for Control of Stadium Project." The subtitle summarizes the article pretty succinctly, "Parking Fight Highlights Strain as Team Fears City Will Bungle Job."

Granted, I can understand their concern. DC as a government appears to have some project management "issues." Nonetheless, the debacle over above-ground and underground parking speaks to fundamentally different objectives held by the Washington National Baseball Club vs. planning and economic development officials from the City of Washington.

Even though I worry about execution, the City is equally concerned about sparking development, creating a neighborhood, a place, whereas fundamentally the baseball team is concerned about making money and opening the stadium. Their only concern is commerce, specifically their profits, not the financial success of any other entity other than their own.

I don't agree that it's absolutely necessary for the parking lots, of whatever sort, to be open when the stadium opens. It's better to build the best, than to satisfice and build something crappy. Crappy is with us for at least 20 years.

But great places stay with us for decades, if not centuries. And they mean more to us than commerce.

From the article:

"The only people who had ever built or operated a stadium, or built a building, were us," Kasten said of a recent meeting with city leaders. "And we are trying as hard as we can to help them avoid mistakes. . . . We need to have this project done on time. We need to have it done on budget. It needs not to be a massive construction zone when it opens."

Stan Kasten shouldn't be so proud of his experience in building a baseball stadium. Because it sure looks like he created a big old construction project disconnected from the City of Atlanta.

It adds little to neighborhood economic development or urban vitality outside of the stadium wall, unless you consider surface parking lots to be vital urban spaces.

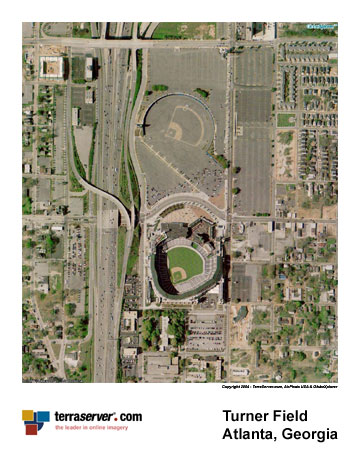

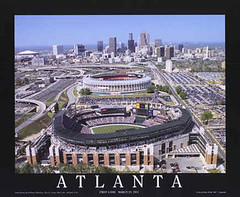

Look at Turner Field, which Stan Kasten built:

Satellite image from TerraServer.

Satellite image from TerraServer. Image from Skyline Pictures.

Image from Skyline Pictures.From the standpoint of enhancing and extending city livability and quality public spaces, clearly Turner Field is a failure. It shouldn't be the example guiding stadium construction and placemaking for the Washington Nationals baseball stadium in DC.

But from a site planning standpoint, this isn't much different from the difference between Tysons Corner Shopping Center, built by the Lerners, and Georgetown.

Tysons Corner Shopping Center is in the background of this photo. Source unknown.

Tysons Corner Shopping Center is in the background of this photo. Source unknown.

This is hardly the best photo of Georgetown, but there are people on the sidewalks, and activity on the street, not just a bunch of sterile parking lots and inwardly focused buildings.

![WrigleyLeft_LR[1].jpg](http://static.flickr.com/58/166113625_83226780c0_m.jpg) Wrigleyville photo by Sandy Sorlien.

Wrigleyville photo by Sandy Sorlien.Urban design-placemaking should be the primary consideration when developing projects such as the Washington Nationals Baseball Stadium.

Also see these previous blog entries:

-- Baseball, Hot Dogs, Apple Pie, and Mixed Primary Uses

-- Siting, site planning, and connection: More thoughts about baseball

-- Baseball, hot dogs, apple pie, and profits... and

-- Tale of Two (or more) Cities.

The latter piece quotes from work by architecture professor and stadium architect Philip Bess:

EIGHT IMPERATIVES FOR TRADITIONAL NEIGHBORHOOD BASEBALL PARKS

■ Think always of ballpark design in the context of urban design;

■ Think always in terms of neighborhood rather than zone or district;

■ Let site more than program drive the ballpark design---not exclusively, but more…;

■ Treat the ballpark as a civic building;

■ Make cars adapt to the culture and physical form of the neighborhood instead of the neighborhood adapting to the cars;

■ Maximize the use of pre-existing on- and off-street parking, and distribute rather than concentrate any new required parking;

■ Create development opportunities for a variety of activities in the vicinity of the ballpark, including housing and shopping;

■ Locate non-ballpark specific program functions in buildings located adjacent to rather than within the ballpark itself.

In closing he tells us that "it is possible to make new ballparks that are neighborhood friendly and generate equivalent revenues as current industry standard stadia, for about 2/3 the cost...."

Index Keywords: stadiums-arenas; urban-design-placemaking

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home