A couple good articles about this, articles that Fred Hiatt of the

Post needs to read...

Why Traffic Congestion Is Here to Stay...and Will Get Worse by Anthony Downs and

Rethinking Traffic Congestion by Brian Taylor.

And an excerpt from my class paper outline (which is labored at the moment...)

The Washington, DC metropolitan region is typical of regions across the United States. The land use and development paradigm is characterized by deconcentration, polycentrism, and segregated uses, and is dependent on personally owned automobiles for transportation in and around the region.

The region continues to expand spatially, and demand for roads and highways continues apace.

While there is capacity for new roadways throughout the suburban parts of the region, especially at a greater distance from the core of the region, for the most part, the center city is "built out" in terms of road capacity in terms of lineal distance. The region does possess a well-used subway system which enjoys ever increasing ridership, and capacity constraints are real and anticipated.

Land use (the size, mix, location, and use of different types of buildings and places) shapes mobility. In the United States, with rare exceptions, mobility planning is dominated by planning for the automobile.

------------------------------------------------------------------------

Capacity of one mile of road-lane for one hour

Limited access freeway: approximately 2,000 vehicles

Typical urban arterial: 800-1,000 vehicles

Typical suburban arterial: 1,300 vehicles

Typical bus service: 6,750 people

Bus rapid transit: 10,000 people

Light rail: 15,000 people

Heavy rail: 20,000 to 65,000 people

(Sources, Tumlin, Jeff. Presentation; Steve Belmont, Cities in Full

------------------------------------------------------------------------

The neighborhoods experiencing the most in-migration and new investment tend to be well-located and/or connected by high quality transit assets, in particular within a 5 to 20 minute walkshed to subway stations.

Surging interest in the city is double-edged. The city's revenue structure is constrained by various restrictions imposed by Congress as well as the fact that 50% of the city's land area is tax exempt. These institutions also enjoy tax exempt status for various other transactions, further depriving the city of tax revenue. Therefore, the City of Washington relies on residents for both income and property taxes (as well as commercial property in the downtown core). Therefore, new taxpaying residents are desired.

On the other hand, because the dominant planning and development paradigm of the last 50 years is one of "sprawl," most city residents, having moved to the city from a suburb, tend to apply the suburban land use and transportation planning paradigm to neighborhood and city-wide planning matters in the City of Washington.

As a place with historical antecedents in "the walking city," urban-appropriate solutions to land use and transportation matters are required.

Given the region's continued deconcentration through spatial expansion, the inability to build enough road capacity given various and real constraints on the use of road capacity, and the fact that the typical suburban household conducts 9-15 trips per day, most by automobile, this paper argues that center cities again possess competitive advantage vis-a-vis other in-region communities in terms of travel efficiency.

To ensure that this competitive advantage is not eroded, it is proposed that an alternative land use and transportation planning paradigm be adopted, one that mandates and encourages that land use and transportation decisions are optimized to encourage and favor the most efficient use of transportation assets. ....

However, for various reasons, including these facts:

(1) DC zoning regulations tend to have been based upon codes originally written for suburban land development requirements;

(2) Land use planning focuses on building and zoning requirements, which for the most part, do not address the impact of parking and other requirements on the transportation system (other than limited requirements to mitigate traffic and/or conduct traffic studies);

(3) Transportation agencies have multiple and conflicting objectives that tend to favor road building and maintenance, and focus on the automobile and automobility in defining the transportation planning framework;

it is argued that the City of Washington has not adopted a planning paradigm that links land use and transportation planning.

Both San Francisco and Utrecht in the Netherlands provide alternative approaches which can be adopted and adapted by the District of Columbia to better link land use and transportation policy and practice.

San Francisco. First outlined in 1973, San Francisco adopted a "Transit First" land use paradigm, first within the city's comprehensive plan, and later in the

Municipal Charter.

The intent of a "Transit First" policy is to promote transit (and walking and bicycling), not automobility, as the primary mobility mode within the city, and to create a set of coordinated governmental policies, regulations, and actions to operationalize this paradigm.

- Policy initiatives in the form of laws and ordinances

- A regulatory regime that implements the ordinances and regulations

- Financial incentives;

- Design guidelines; and

- Capital improvements.

However, a cursory review of materials available online determines that not all transportation advocates believe that San Francisco has operationalized this policy in ways that satisfy all proponents.

According to TLUC, critics say that the city officials kow-tow to developers and still allow projects that encourage automobiles, provide subsidized public parking structures and regularly approve parking garage construction in the downtown core.

Echoing these criticisms,

Rescue MUNI, a San Francisco transit advocacy organization, has suggested several changes that would strengthen the City's Transit-First Policy, including making specific reference that the objective of the transportation system should "be the efficient movement of people and goods; rather than the movement of automobiles," calling for the installation of transit priority physical improvements (e.g. bus priority traffic lights, bus only lanes, etc.), and the adoption of parking policies that discourage automobile use while encouraging public transit.

Livable City(TLC) has also criticized the lack of implementation of the City's Transit-First Policy and has also offered a program, "

Great Transit for a Livable City," to improve the situation.

Utrecht. In the Netherlands, the City of Utrecht has adopted an "ABC location policy" which classifies "development areas according to the conditions of transport." Places are rated based on their public transit infrastructure and automobile accessibility.

- A places have excellent public transit capacity and limited automobile capacity

- B places have both good public transit and automobile access

- C places have poor public transit and excellent automobile capacity.

Sites are rated and building uses are directed to the locations that can best accommodate both the land use and transportation system requirements in ways that maximize national transportation planning priorities of prioritizing road use for business use, public transit, car-sharing, and bicycling.

Framework

While not a full outline, this paper intends to explore the policies, regulations, and frameworks necessary to implement a form of a "Transit First" land use and transportation planning and regulatory regime for the District of Columbia.

This will include exploration of:

- A Master Transportation Plan for the District of Columbia focusing on "the efficient movement of people and goods; rather than the movement of automobiles"

- Transit capacity increases

- A form of ABC accessibility planning appropriate for DC, especially in association with transit-oriented development and other compact development strategies

- Weighting parking requirements according to distance to transit stations

- Linking new development projects to transit enhancement

- Transportation Demand Management including:

- TDM planning requirements for institutions along the lines of ABC accessibility planning

- Time shifting freight deliveries to times when the road network is underutilized

- The creation of "Transportation Management Districts" for mixed use commercial and residential districts.

-----------------------------

And there is even more crazy stuff that I should work on ranging from Portland's transit withholding tax on businesses, which allows Portland to provide free transit in the downtown core to considerations of congestion taxes (which I don't really think is an issue so much for DC, as much as it is for other parts of the region and choke points within).

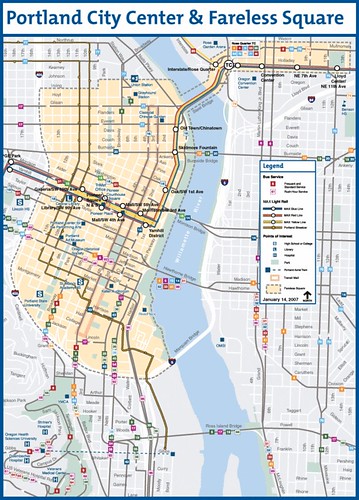

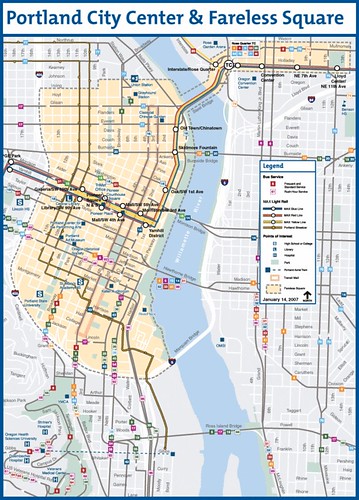

[At the time of publication] Portland's Fareless Square (shaded in orange) provides free use of all modes--bus, streetcar, and light rail. [Due to budget crisis post-2008 recession, the Fareless Square ended.]

Labels: land use planning, transportation planning

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home