Congestion pricing and tolls aren't magic bullets; DC needs a linked paradigm for transportation and land use planning; DC needs a transportation plan

-----------

Note: this entry has changed quite a bit and is worth re-reading. I also changed it today (Monday) but won't be changing it anymore as my focus shifts to the actual paper. As stuff gets into this from the paper, it's less well-formed.

-----------

From Northwest Environment Watch.

One of the reasons that I testified against the Comprehensive Plan last year is because the Transportation Element was pretty under-formed. If you compare it to the Arlington County Master Transportation Plan (draft) you'll see what I mean.

Arlington intimately links transportation and land use planning. Plus, the overarching philosophy undergirding their plan(s) is reducing the number of single occupancy vehicle trips because this is the least efficient form of mobility, one that is increasingly difficult to support in terms of cost and capacity. Plus SOV trips fail to leverage the billions of dollars invested in the area's public transit system, especially subway. (A linked transportation and land use planning paradigm also adjusts parking requirements.)

DC has some advantages over Arlington. DC was designed for the most part before cars, and the "walking city" based urban design makes getting around in ways other than automobiles reasonably efficient. DC has 40 subway stations. While this is nothing compared to London, NYC, or Paris, it's almost 4 times as many as possessed by Arlington.

But Arlington's Transportation Plan systematically addresses overall objectives including TDM, mode, and infrastructure (streets). Each element in the plan covers its role in "Achieving Arlington’s Overall Transportation Goals" which are:

1. Reduce Single Occupant Vehicle (SOV) Trips;

2. Provide High Quality Transportation Service;

3. Establish Equity;

4. Administrate and Manage Effectively;

5. Achieve Environmental Sustainability.

Stating that "Reduc[ing] Single Occupant Vehicle (SOV) Trips" is a fundamental priority of the Master Plan shapes the entire plan, something that the DC Transportation Element really lacks, an overarching goal and framework.

But we have other issues. DC's road capacity is for the most part finite--it can't be expanded. The same goes for on-street parking spaces, especially in neighborhoods.

And, the WMATA subway system, at least in the center city, will reach capacity, and too few people seem to be acknowledging and planning for this reality--the people at WMATA who did try to address this around 2000-2003 have by 2007 mostly been fired. And the new WMATA president is oriented towards operations, not to long range planning. This is disastrous for DC in particular, but also for the region more generally.

But there is no question that Arlington links transportation and land use planning in ways that don't seem to be on DC's radar. This despite the fact that DC isn't encumbered in the same fashion as Arlington. DC can enact transportation demand management planning without needing authorization from a State Legislature. DC is a city, county, and state all in one.

Despite not doing all the great linked planning that Arlington does, DC has 45% of daily work trips by transit, walking, and biking, compared to Arlington's 30%. Plus I imagine more people in DC use transit to get around as their primary transportation mode for non-work trips. (Just think if the city tried. Just think if we had decent transit marketing.)

Why I am writing all this?

Because of two troubling articles in the paper over the last few days. First, Marion Barry suggests that DC assess tolls on people coming into the city by car. See "Barry urges worker tolls" from the Washington Times. (Note my alternative is a transit withholding tax, comparable to what is done in Portland and Eugene, Oregon. This would assess all people working in the city, including the 70% who don't live in the city. Although it wouldn't tag those that merely drive through the city without stopping to get to Virginia and Maryland.)

Given the very real bottlenecks present in entering the city, especially from Virginia--only three bridges, four if you count the Wilson Bridge--the mere process of collecting tolls would astronomically increase the amount of delay and cost of congestion in ways that are almost unfathomable.

Second, yesterday's Post reports that DC is looking for $ from the federal government to study congestion pricing. See "U.S. Funds Sought for D.C. Traffic Study."

For various reasons I am skeptical of congestion pricing. Yes, there is congestion in the city for cars (and now the subway) particularly at certain times of the day.

Traffic comes to a standstill on the beltway in Virginia near the Maryland line during the evening rush hour. Photo By Michael Robinson-Chavez, Washington Post.

However, I suspect that the worst, most continuous congestion in the region is actually in the suburbs. Regardless, without conducting transportation demand management-based planning generally, DC has no business putting congestion pricing proposals forward, other than to be just like Mike (Bloomberg). To use lots of cliches, this is putting the cart before the horse.

There are plenty of missed opportunities in the DC planning and zoning regime now that would reduce congestion, without moving to congestion pricing.

People Powered. The Big Idea: A system of signs posted along Chicago's lakefront would inform drivers and bicyclists of the human, financial, and environmental benefits of riding a bike to work versus driving a car. Kimberly Viviano, Courtesy Viviano + Company

Plus the politics. I can't imagine Congess not getting involved. Hell, Congress made the taxi zones the way they are, just to make trips from the Capitol to most areas of Downtown the cheapest of all taxi trips in the city. Hell/2, Congressional workers get free parking. I know of people living within 10 blocks of Congress who drive, just because they have free parking. And Capitol Hill is one of the most walkable communities in the United States.

Drive time, image by David Clark (via The Washington Times)

In fact, I argue that in the time of rampant automobile use, DC possesses renewed competitive advantages around mobility. Commuting times for DC residents aren't much higher than the national average, despite the fact that the DC region is #3 nationally for congestion. With great subway connections it's easy and efficient to get around many parts of the city without a car. Bus service is pretty good, although people denigrate it, and some lines do have consistent seemingly addressable problems that go unaddressed. But transit is cheaper than owning a car, especially if you live and work in the city.

DC needs to first link transportation and land use planning, policy, and regulations. In fact, this is a paper I have been writing, about what an ideal paradigm would look like.

Below is an outline from my paper about this. The structure isn't as elegant as I would like. It's rough, and comments would be appreciated.

----------------------------

Philosophical Foundations/Current Conditions

1. Accessibility to places as the foundation for linking transportation and land use planning

In “Accessible Cities and Regions: A Framework for Sustainable Transport and Urbanism in the 21st Century,” Robert Cervero writes that:

Accessibility – as an indicator of the ability to efficiently reach oft-visited places – has gained increasing attention as a complement to the more traditional mobility-based measures of performance in transportation planning, such as ‘average delays’ and ‘levels of service’. Evaluating performance from an accessibility perspective provides a balanced, more holistic approach to transportation analysis and planning. Notably, it gives attention to alternative strategies for reducing traffic congestion and mitigating environmental problems, such as promoting efficient, resource-conserving land-use arrangements.”

Accessibility is a product of mobility and proximity, enhanced by either increasing the speed of getting between point A and point B (mobility), or by bringing points A and B closer together (proximity), or some combination thereof. In this sense, an accessibility-based approach gives legitimacy to land-use initiatives and urban management tools….

Although not a replacement for supply-side strategies and mobility-based planning, looking at cities from an accessibility perspective in many ways reframes objective functions. Casting the objective as one of enhancing accessibility shifts the focus to people and places. (p.2)

2. Accessibility matters only if there are great places to live, work, and recreate. High vitality Central Business District, high vitality city neighborhoods. Downtown and center city. neighborhoods. Complete streets/neighborhoods. (to come) Belmont.

Belmont writes:

Where automobile dependence reigns, every housing unit, even a townhouse or apartment, creates demand for pavement in many locations--supermarket, shopping center, school, church, exercise club, barber shop, restaurant, and on and on, not to mention all the roadway pavement needed to connect the housing unit to all the parking pavement. Only in cities can significant reductions in per-cpaita parking acreage be achieved (213).

3. DC's major competitive advantage in a traffic-engorged region is accessibility--the ability to get around in a comparatively efficient manner within the center city, when compared to other areas within the region, especially high in demand submarkets. This is due in large part to the rich transit infrastructure afforded by the WMATA subway system, linked with the mobility-efficient urban form that results from the L'Enfant Plan.

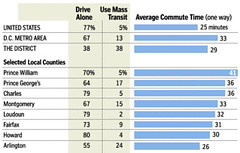

The DC Metropolitan region is ranked #3 nationally in terms of the costs and amount of congestion. Yet, the commuting times for residents of DC proper are not significantly greater than the national average. Furthermore, compared to outlying areas of the region, commuting times for DC residents are significantly lower. (Note that for Arlington County residents, linked transportation and land use planning has paid off, as the average commuting times for County residents is only 1 minute greater than the national average--in a region of high congestion.)

Washington Post graphic.

This competitive advantage must be strengthened at every turn by ensuring that land use and transportation policies, programs, regulations, and decisions contribute in positive ways to enhanced mobility.

In some respects, this means that a DC-centric perspective needs to be adopted when considering broad transportation issues. Responsibility for transit expansion is devolving to the individual jurisdictions. (A mistake, but...)

Additionally, efficient non-automobile transportation modes available within the city allow residents to satisfy a goodly amount of non-work trip demand without using an automobile. In this case, transit (and walking and bicycling) use is part of a broader lifestyle, rather than merely a way to get to work.

4. At the same time, DC transportation planning must recognize the centrality of DC as a regional destination, and the utilization of the transit system by non-resident employees and visitors. This requires that DC specifically plan and manage the city's transportation system in a manner that achieves efficient mobility, reduces intra-city congestion, and ensures adequate capacity within the heavy rail system, to serve employers, employees, attractions, and visitors across the city generally, and specifically within the Downtown and Center City. DC's Center City is the primary work destination in the region, and 70% of workers employed within the District of Columbia are non-residents.

5. DC transportation supply, particularly roads and on-street parking, is constrained. For the most part, new roads can't be built, and new lanes can't be added to extant streets (except on streets that L'Enfant thought would be much bigger than they turned out to be such as on K Street NE, which L'Enfant expected would be a major route west through the city, from the main route along the Eastern seaboard that linked Boston, New York, Philadelphia, and Baltimore to DC, via Bladensburg Road).

Automobiles tend to be efficient for individuals, but are resource-inefficient in terms of the demand for roads and parking. DC-centric transportation policies need to stress alternatives to the car, specifically transit, walking, and bicycling, to best utilize transportation infrastructure and supply. Where possible, efficient transportation supply expansion needs to be considered. Generally, this is likely to be some form of expansion of transit services.

Transit expansion, Core Capacity Study, transit city definition, underground, expense

(Insert GE streetcar ad, Tampa or Charlottesville Dan Burden type graphic, Passonneau diagram from the 1977 Central Washington Traffic and Urban Design study. Data from Jeff Tumlin)

6. Fears of "inward suburbanization*." The dominant planning and land use paradigm of the past 50 years has been suburban, focused around automobile connectivity to segregated and relatively low-density uses. With the rise in interest in urban living in DC (and other urban centers, see Birch, 200X), people imprinted with this sub-urban paradigm are relocating to the center, but rather than adapt to urban mobility patterns (and urban design principles), most frequently such residents attempt to apply suburban-appropriate answers to fundamentally urban questions, in ways that are deleterious to maintaining and extending the quality of life in walkable and compact neighborhoods. (* This phrase was coined by Stuart Sirota.)

The Williams Administration set a stretch goal of attracting 100,000 new residents by 20XX. If each of the households attracted through residential attraction programs relied upon automobiles for the majority of their travel, intra-city congestion generated by residents would exceed the demands put onto the system by non-residents, clogging arterial, collector, and neighborhood streets beyond the capacity of the system.

[7.? Mobility shed concept. Extyension of the idea of TAZs, catchment areas, and commutershed. Providing a foundation for how to consider mode shift, the provision of transportation services, the integration of modes, and marketing. ]

Policies

1. Zoning regulations must change from the current focus on bulk and height of individual properties and instead link land use regulations to transportation supply and demand.

Evaluate places based on projected use demands for mobility and the ability of the area's transportation infrastructure to meet the demand. Linking transportation requirements to land use decision making and regulation. The suggested changes in the new Comprehensive Plan for zoning regulations that would link transportation and land use planning are minimal and insignificant.

Accessibility planning. In the Netherlands, the City of Utrecht has adopted an "ABC location policy" which classifies "development areas according to the conditions of transport." Places are rated based on their public transit infrastructure and automobile accessibility.

- A places have excellent public transit capacity and limited automobile capacity;

- B places have both good public transit and automobile access;

- C places have poor public transit and excellent automobile capacity.

Sites are rated and building uses are directed to the locations that can best accommodate both the land use and transportation system requirements in ways that maximize national transportation planning priorities of prioritizing road use for business use, public transit, car-sharing, and bicycling. Parking requirements are scaled according to the availablity of transit, and transportation demand management planning systems are in place to shape optimal mode shift targets. (European Academy of Urban Development, 1998).

In DC, zoning regulations are about the lot, not about the surrounding context or the impact beyond the lot of what happens on the lot. Linking use to place in terms of the impact on transportation infrastructure should trump current matter of right provisions in DC Zoning regulations.

2. Zoning regulations must change from the current focus on the bulk and height of individual properties to a focus on extending and enhancing urban form. (See the first sentence of the introduction to this blog.)

Reinforce urban design, on maintaining and extending the qualities of compact amenity rich neighborhoods, walkability, and complete streets. Streets have been primarily designed to accommodate automobiles. Rebalancing right-of-way to better serve transit users, pedestrians, and bicyclists. DC Department of Transportation has begun to make this shift. Wide variety of streetscape initiatives, Georgetown, the Barracks Row Main Street district of 8th Street SE, Benning Road, H Street NE, the 12th Street NE in Brookland. Mt. Vernon, Columbia Heights. (BR as an example. Rachel’s paper. Still a struggle. LOS for cars vs. LOQ. Dan Burden.)

3. Creating a DC-centric transportation policy as it relates to public transit.

According to Belmont "political realities and false economies produce regional rail systems that bypass distressed central neighborhoods as they stretch far into suburbia, catering to park-ride passengers--mostly downtown workers opting to avoid the cost and inconvenience of downtown parking. New generation [suburban] stations pspawn parking pavement rather than architecture (247).

"Can new-generation systems be centralized by adding stations to the central portions of far-reaching lines? To do so would undermine the investment already made in the more distant stations. The two tasks of hauling some passengers short distances and other passengers long distances are at fundamental odds with one another, yet most new-generation systems are meant to do just that. (258) NYC local and express with separate tracks. Long distance regional trains cannot attract suburban passengers unless it avoid the extended travel time imposed by many closely-spaced central-area stops.

Investment in transportation infrastructure is complicated by competition amongst the municipalities and counties within the region that are seeking investment.

Reach SF 7, NYC 15, DC 15, Paris 7.5

Station density

Proposals for extension of Metrorail beyond Greenbelt, Suitland, Inner Purple vs. outer purple, Dulles. Brosnan presentation to NBM in 2001 or 2002-- how to kill DC. DC as jobs center in the region surpassed by Fairfax County Devolving of responsibility for transit expansion from WMATA to individual jurisdictions.

Despite the polycentric form of the Washington Metrorail system (Belmost, XXX), the presence of relatively dense rowhouse neighborhoods adjacent to the Downtown (Passonneau) and the historic preservation movement, which provided a way to preserve the attractiveness of these close-in neighborhoods (Logan XXXX) for urban-centric residents attracted to the qualtiy of the building stock and the proximity to work either for the Federal Government, or the vast array of organizations (law firms, associations, contractors, consultants, etc.), combined with the relatively dense number of Metrorail stations in the core of the city (providing a kind of monocentric impact at the heart of the city) meant that the impact of .. Fundamentally different from "new-generation" rail constructed in cities such as Atlanta or Miami. Even systems considered to be wildly successful, such as Dallas or the MAX system in Portland, Oregon have markedly fewer riders when compared to DC. (APTA?)

4. Making the provision of high quality transit "the law" comparable to San Francisco's "Transit First" policy.

First outlined in 1973, San Francisco adopted a "Transit First" land use paradigm, first within the city's comprehensive plan. Later, this paradigm was passed as an amendment to the Municipal Charter, and therefore is part of the city’s system of laws. The intent of a "Transit First" policy is to promote transit (and walking and bicycling), not automobility, as the primary mobility mode within the city, and to create a set of coordinated governmental policies, regulations, and actions to operationalize this paradigm.

According to the Transportation and Land Use Consortium (TLUC) of the Bay Area, this requires that the city coordinate:

- Policy initiatives in the form of laws and ordinances;

- A regulatory regime that implements the ordinances and regulations

- Financial incentives;

- Design guidelines; and

- Capital improvements.

5. Balancing transportation modes (Vuchic)/Enacting Transportation Demand Management as Policy.

TDM and mode shift as the primary organizing principle for linking actual demand/use for transportation and land use planning. Require TDM planning for all institutional uses. Require TDM for DC Government agencies.

Examples of DC Government policy errors based on the failure to have TDM requirements:

a. residential parking permit policies

b. preferred parking for firefighters

c. church parking debacle

d. relocation of DC government agencies to areas with a paucity of transportation linkages

e. baseball stadium location vs. Verizon Center location

f. DC Board of Zoning Adjustment refusal to consider TDM issues in zoning matters.

g. others ?

cf. good decision, dedicated parking spaces in neighborhoods, primarily in commercial districts, for carsharing services

From Living Streets exhibit, NYC.

Practices, Programs, and Regulations

Having a linked transportation and land use planning paradigm in DC would lead to a number of changes regarding "how things are done around here" including:

1. Implementing Transportation Demand Management Practices and Regulations. All institutions should have to implement transportation demand management planning with the goal of a substantive reduction of single occupancy vehicle trips. Transportation Management Districts should be created to organize TDM planning within business districts, including neighborhood commercial districts. Shared management and utilization of parking resources should be encouraged. The focused promotion of transit, walking, and bicycling should be at the top of the TDM agenda. The Board of Zoning Adjustment and Zoning Commission must be required to address the TDM aspects of any and all matters before them. Whenever possible, freight deliveries should be timeshifted to periods of relatively low transportation demand.

2. Focusing new development towards areas with extant infrastructure. This includes traditional commercial districts, which tend to have an urban form that supports transit.

3. Requiring proffers and the funding of new transportation infrastructure as part of large greenfield and greyfield re/development projects. This would be comparable to how the Portland Streetcar system was developed to serve the Pearl and Waterfront districts. In DC, McMillan Reservoir, along M Street SE, Armed Forces Retirement Home, and the St. Elizabeth's site among others are examples of places where the approval and construction of proposed development projects should be linked to the partial funding of transit expansion on the part of the developers.

4. Revise zoning regulations regarding parking/Implement substantive parking and curbside management policies based on TDM, with differential policies for residential and commercial areas. Address current parking requirements in terms of induced driving (Shoup). Adjusting parking requirements, downward or none, for different types of buildings, in different places--Downtown, in traditional commercial districts, and within a certain distance from substantial transit infrastructure (subway stations, streetcar, major bus transfer locations).

Adjust residential parking policies. Communicate directly about on-street parking inventory on a neighborhood by neighborhood basis. Look at the College Park example of public parking meters on private lots. Need to try to get data on DC on-street parking inventory, especially at the neighborhood level. On street parking supply is finite and multiple cars per household should be discouraged through policy and pricing policies.

Seattle doesn't have parking minimums for Downtown in their zoning regulations. They are extending this policy to their next level of transit-connected urban villages within the city, as well as in the areas served by their forthcoming light rail stations.

As part of Seattle's re-write of the city's Neighborhood Business District Strategy, parking requirements in zoning were reassessed for the entire city, based on a massive inventory of parking use across the city. One of the changes is to reduce the number of spaces required in multiunit housing buildings, because their research found that car ownership decreased in relation to the number of units in a building.

And note, while having perhaps the best bus system in the United States, Seattle currently does not have light rail or heavy rail transit, which by comparison to bus is much faster and more comfortable, and has higher customer satisfaction ratings.

5. Funding and management issues and a DC transit policy with regard to the provision of public transit services (WMATA). WMATA does not have dedicated funding source. Federal issue. The Feds should pay money into WMATA every year regardless of the initiative by Congressman Tom Davis.

Because of the devolving of planning for expansion to the individual jurisdictions, DC needs to represent.

Congestion pricing vs. withholding tax. Sidebar on congestion (I think the most congested areas in the region for the most part are in the suburbs). Transit withholding tax as a way for DC to fund transit expansion.

6. Transit supply issues generally. Use the concept of the "mobility shed" to shape planning. Issue of transit use for work-related trips versus transit use as a lifestyle choice more generally. More neighborhood based services to get people to subway stations without driving. Streetcars. Bus "rapider" transit and circulator services.

Long term issues of railroad service (inter-city transportation) and the need to plan for subway system capacity increases in the center city due to reaching projected capacity given current system capabilities in terms of headway, subway car configuration, and length of trains.

Most of the WMATA personnel who spearheaded planning the proposed "separate" blue line from Georgetown to Fort Lincoln, to provide two new tracks serving the center city have been fired by now. (This plan was proposed back in 2001-2003.) This plan needs to be revived. It would take 10 years to build another line (DC isn't Barcelona). So this kind of planning must start sooner rather than later.

7. Consider the creation of a "fareless square" for the provision of bus service within DC. Suggest not "fareless square" like Portland, which covers the streetcar, light rail, and bus, but at a minimum free bus services across the entire city. There would be some logistical difficulties, especially with border-crossing routes, and non-resident free riders using service on the border of the city and Maryland, but cities like Pittsburgh and Seattle manage to deal with the issues of charging and non-charging areas. This has an advantage of also meeting equity objectives for transit service. (See the Resources for the Future paper.)

The reason to exclude the subway from a fareless square (unlike Portland, Oregon, and limited subway service within Downtown Pittsburgh) has to do with the managerial and political difficulties and the fact that so many users of the stations in DC are not DC residents. DC already subsidizes the suburbs because the method for paying for WMATA services is based on the number of subway stations in each jurisdiction. DC is a destination for many of the region's residents, but they end up not paying their fare share of the non-farebox revenue cost of service.)

Trying to get info from a contact at Metro about how much DC pays for Metrobus services, and an estimate of farebox revenue. Need to run down estimate of earned income in DC. 30% of workers live in DC. 70% do not. Figure out if a reasonable withholding tax can generate enough money to cover this.

8. Improving and enhancing transit marketing. (to come)

See:

-- Making Transit Sexy

-- More on Metro and rethinking transit marketing

-- An interesting transit idea: volunteers

-- More on bus marketing in Pittsburgh

-- Bus shelters revisited

-- The first priority for Bus shelters ought to be marketing transit

-- Speaking of bus marketing part 2

- market segmentation

- input, throughput, and output publics

- marketing concept and marketing imagination

- information and wayfinding at stations and bus stops

- websites. Arlington County, Arlington County Commuter Page and blog, Transport for London vs. WMATA, DDOT, goDCgo

- ride guide as web code

- distribution of information within the community/guerilla marketing

Labels: land use planning, mobility, transit, transportation planning

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home