Time passages or the temporal dimension of land use and development

The central business district of most major cities went through a number of iterations before the result that we see today. Buildings were constructed and later torn down and built bigger and better. At a talk in 2002, Andres Duany made the point that during the period of primary development of our cities, when this happened, the new that replaced the old generally was much better than what it replaced, and so people favored the changes, but in the period after World War II, this calculus of the new being better than the old changed, that the new more often than not was worse. (If you haven't read James Kuntsler's books Home from Nowhere and Geography of Nowhere on this point, you need to.)

This point resonated with me because in college I read a paper by Alexander Gerschenkron on the "Economic Advantages of Backwardness." The basic point is that later developing economies can benefit by adopting the latest technologies during their period of industrialization, rather than having to go through iterations of improving technology, that they can jump start the process.

So I find how both Rockville Pike in Montgomery County ("Readying Rockville Pike for Renewal: Idea of Overhaul Is Popular but Faces Hurdles " and "White Flint Stands Out in Plans for Rockville Pike " from the Post) and Tysons Corner ("Tysons Plan Poised To Move Forward," "Planners See Sleek Future For Tysons," and "Where the Car Is King, Tysons Faces a Dilemma" from the Post) are looking to strengthen the building fabric and urban form of what are now automobile-centric places to be very interesting, especially in view of the op-ed of the pro-suburban geographer Joel Kotkin from the Sunday Post, "Turns Out There's Good News on Main Street."

Rockville Pike, looking north, which Montgomery planners want to transform into a network of urban villages. Photo Credit: By Bill O'leary -- The Washington Post Photo

(Note that not everyone buys into the changes. See this op-ed, "The Costs of Redeveloping Tysons Corner" from the Post. This doesn't sound any different from many of the pro-automobility arguments I hear in planning discussions in DC neighborhoods, where you would think that people are more clued into the value of transit and walking and bicycling.)

Like a lot of ungrateful children (I am one of them) who leave home without respecting what we received from our parents, the suburbs in Kotkin's eyes, are ready to finish kicking the city to the curb (maybe).

Usually his pieces, such as "Hot World? Blame Cities," are more about screw the city--in my opinion anyway. Even a piece like "City Of the Future; Unless it keeps its citizens safe, the modern metropolis may go the way of ancient Rome," which makes good points, doesn't propose ways of equalizing tax revenues between cities and suburbs so that cities have the money to address the problems that they are in part saddled with by the suburbs. For that you have to look to others, such as the work of Myron Orfield.

But the reality is more complicated. For the first time in a long time, I didn't mind Kotkin's piece, which is focused on making the important point that suburbs, at least the inner and middle rings, are maturing and they are maturing in a manner that in some respects disconnects the suburbs from having to rely on the center city, either for jobs or for culture.

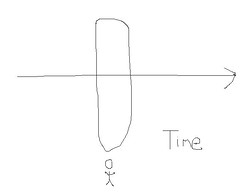

Unlike many other bloggers, I don't have much in the way of graphic design skills, but last year I produced this hokey graphic to illustrate the point that time marches on/is a continuum while we are focused more on our moment in time, rather than the continuum.

(Produced for a presentation I made about thinking about public history and DC.)

The reality is that the suburbs are on a different maturation timeframe than the center cities which parented them. Places that developed around automobility are ready to develop in ways that support walking and transit. Bethesda Row or the new Rockville Town Center (see "A Piazza for a Maryland Suburb" from the New York Times), which finally gets the "town center" thing right after a few failed tries, demonstrate that the suburbs don't need to look to the center city for evening activities or culture.

In fact, the VisArts center in Rockville at the Rockville Town Center is an example of a high quality media-oriented arts center that doesn't exist in any form in DC, which is both an example of the maturation of the suburbs as well as a lesson about what DC spends its resources on. Similarly, why can Montgomery County figure out how to build new libraries, such as the one at Rockville Town Center (see "Dithering Over D.C. Libraries" from the Post) while DC finally seems to be getting right after many false starts taking many years.

Or, how Arlington County can build mixed-purpose public facilities, such as the Shirlington Library which includes the Signature Theater, while DC continues to build separate use facilities such as separate libraries, separate recreation centers, and separate senior wellness centers, without taking the time to rethink how these services are provided in ways that can yield breakthough ideas, performance, and outcomes.

There are other ways to think about this broad issue of the suburbs and the center cities, say in terms of the "center-periphery" argument from development economics. This is an excerpt from the Dictionary of Social Sciences:

Describes patterns of unequal relations between relatively developed centers and less developed outlying areas within an economy or other system. Although Marxist theories of imperialism by Vladimir Ilich Lenin and others prefigured these issues in the first decades of the twentieth century, core–periphery models emerged in the late 1950s in an attempt to explain a more narrow set of economic observations: uneven development and relations of dependency within countries, particularly in developing economies where the progress toward a gradual economic equilibrium between areas was patently absent.

Now the core in many regions, especially those in decline (Detroit, Cleveland, etc.) is shifting to the suburbs. And the challenge is for the center city, the old "core," to continue to mature, grow and improve to remain competitive within metropolitan regions. (This is why I like Michigan's Cool Cities program, even if it isn't realized in a manner I would prefer. Even cities like Detroit have neighborhoods that are competitive in the metropolitan context. Those neighborhoods need to be strengthened, and resident and attraction programs developed to stabilize and maintain and strengthen those advantages.)

It pains me to no end that suburban developers are monetizing "urbanism," creating the kinds of fun, walkable, inviting places that the city had, but has let languish (suburban outmigration and disinvestment helped) while in turn the city has been reshaping its land use patterns in favor of the automobile, as well as diminished beauty and quality.

Transit and the city's legacy urban design provides the competitive advantages the center city can harness in the 21st Century. If we can manage to throw off the yoke of parochialism around our moment in time, and be more willing to grasp the threads of the continuum, and recognize that the land use and development decisions we make today have multi-generational impacts.

Just as the suburbs are recognizing the need to strengthen their urbanization, in some respects along the "transect" idea, so too must the center cities take advantage of the opportunities they possess to leverage transit and location to stabilize and strengthen those factors which make urban living desirable (a la the points made by Dan Burden in this article, "How Can I Find and Help Build a Walkable Community?").

This is at the core of neighborhood arguments about change in places like Brookland or even over the Wisconsin Avenue Giant Supermarket as recounted in pieces over the last couple issues of themail. As long as the center city keeps orienting towards the car, it loses its competitive advantages. What needs to happen instead is that like the suburbs, more automobile oriented parts of DC need to be shaped towards a less automobile-dependent mobility paradigm. This is the next stage in the city's development, a period in which the city is growing in population, not shrinking.

Labels: car culture and automobility, intensification of land use, invasion-succession theory, sustainable land use and resource planning, urban design/placemaking, urban vs. suburban

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home