Saving the U.S. means rethinking mobility AND LAND USE

Streetcar on F Street, postcard image. Note pedestrians, cars, a horse drawn carriage, and a streetcar.

I was reading the latest issue of the Sustainable Transportation Magazine from the Institute for Transportation and Development Policy, and one of the articles is on Bogota. It mentions in the course of the article that the transportation director there is termed the "Secretary of Mobility." (That will end up in my forthcoming DC Transportation Vision Plan/Wish List for 2009.) Note that the magazine is published annually, and the current issue is not yet available online.

Ironically, because I just reprinted an entry from 2006 which discusses the problems of the U.S. automobile industry long before they came to the Federal Government for massive loans, there is a piece in today's New York Times about how technology and some changes in approach (business model) can save the automobile industry, in "Four Ways for Detroit to Save Itself," by Sebastian Thrun and Anthony Levandowski.

Technology isn't the problem (of transit) so much as how the U.S. organizes land use and mobility.

Of course, this piece is going to "anger me" from the outset because it makes the point that despite all the money spent on mass transit, fewer than 1% of work trips use transit.

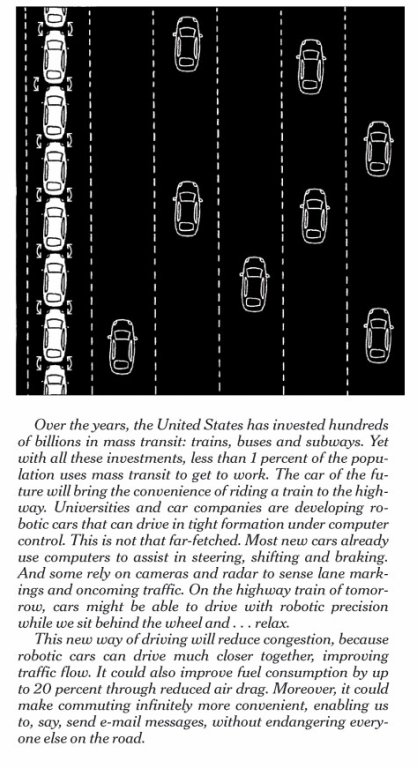

Frame two of the Thrun and Levandowski article. New York Times image.

I am surprised to see this in the New York Times, because in NYC, more than 50% of people ride transit to work and close to 50% of New York City households do not own cars, and it is a perfect example of when land use and transportation policy and transit systems are coordinated at a deep, wide, and intricate level, then automobility is trumped.

Of course, the subway system in the Washington, DC region shows this also. When you have concentrated land use, mixed use, and density of buildings and population, you yield high transit use and reduced automobile use and ownership. The varying impact of the subway system in the DC region on these factors is a perfect example of" how to." Take areas like the core of DC, the Wilson Boulevard corridor in Arlington, Silver Spring in Montgomery County as pro-examples, and areas outside of DC's core within DC, Fairfax County, Prince George's County, etc., as examples of where transit doesn't accomplish as much because there isn't supporting land use and urban design policies which embrace and extend the value of transit.

And of course, the fact that Detroit as a city is a disaster is another example. My joke about Detroit, being that it is criss-crossed all over with freeways and arterial roads, and is relatively undense these days (Detroit never had rowhouses as a housing-building-neighborhood type, unlike the East Coast cities, and Pittsburgh and Chicago), is that its decline is exactly what the automobile industry wanted to have happen to center cities, to force people to need automobiles to get around. Before the destruction of streetcar systems, center cities were a pretty good "mobility technology," having high connection between job location and housing location, and efficient public transit systems to get people in between.

When you have deconcentrated and homogeneous land uses, of course transit isn't going to divert many trips.

GE Streetcar ad, 1940.

So yes, point two in Thrun and Levandowski's article "angers me." And their "solutions" won't really help the automobile industry all that much. Technology isn't the issue. How they build cars, how the business system is organized, how U.S. companies have a much different system in terms of pension and the provision of health insurance compared to their competitors, and legacy costs are more important.

As is the cost of gasoline. Europe has the highest cost gasoline in the world, the cost mostly due to high excise taxes charged to reduce the use of cars and to pay for road infrastructure as well as transit. But Europe still has some of the most successful car manufacturers in the world including BMW, Mercedes, and VW. Both the European divisions of GM and Ford do reasonably well also. (Their fortunes wax and wane given how much involvement they have to deal with from the U.S. parents.) Even Fiat seems to be doing much better. Nissan-Renault is positioned to remain a successful company, with one foot in Europe and the other in Japan.

Raise gasoline taxes significantly in the U.S. and the locally based industry will be forced to rightsize and become competitive on the same basis as the companies in other countries, where the business model and conditions are already at the same point where they are moving towards in the U.S.

But technologizing the car industry won't help the U.S. all that much, because we need to spend less money as a nation on road infrastructure, and as households, especially if we are to see income declines of a significant nature and we are to cope, we need to spend less money on transportation.

The typical U.S. household spends around 20% of total income on transportation (mostly buying and maintaining cars). An urban household in a city like New York City, Washington, Chicago, Philadelphia, or Boston can easily spend less than 3% of their total income on transportation, given the widespread availability of public transit. That leaves a lot more money to be spent on other things. In our case, that "extra" money is spent on an amazing house.

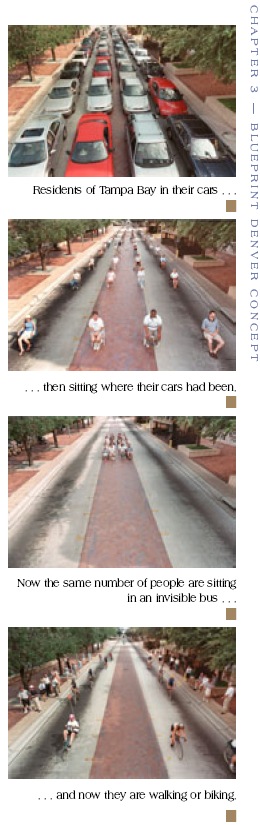

Each of these images shows 40 people and how different modes take up vastly different amounts of space to move the same number of people. People in Tampa. Image reprinted in a Denver planning publication.

Labels: car culture and automobility, change-innovation-transformation, mobility, sustainable land use and resource planning, transportation planning, urban design/placemaking

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home