The Washington Post nails it: summarizing the point of historic preservation designation in one sentence

While not happy about Washington Post columnist Marc Fisher's consistently negative take on historic preservation ("Putting Home's Appearance Ahead of Helping Frail Couple," "Chevy Chase DC Rejects Historic Status," "D.C. Lets Church Tear Down Brutalist Atrocity") over the years, shockingly in an editorial today, "History Lessons: What the Montgomery County Council should consider before it changes the rules for identifying noteworthy sites," about the possibility of changes to historic preservation laws and protections in Montgomery County, Maryland, the 21 words of the last sentence directly and succinctly make the basic point of what matters most in historic preservation:

But what ultimately determines if a site is designated as historic should be whether it is historic, not who owns it.

Frankly, that's a shocking repudiation of just about anything written about historic preservation by the Post's "metro" columnist. Marc has usually come out against preservation protections in favor of individual concerns that in his opinion, for whatever reason, justify exceptions to broader protections.

Instead the Post editorializes that what matters is whether the building is historic, not who owns it, that individual exceptions aren't and shouldn't be the primary determinant of what matters, of what gets designated.

Go Washington Post Editorial Board!

The previous sentence in the editorial does discuss what the paper sees as potential abuse of the system:

The system of historic preservation has always been liable to abuse by neighbors eager to prevent construction.

I will admit that this can occur. But using the word "abuse" is a slippery slope. Part of the problem with historic preservation law and regulations is that people's understanding of what is deemed worthy of historic designation hasn't caught up with historiography, public history, and broader ideas of what matters such as the concept of the cultural landscape.

Typical opposition falls into two camps, either:

-- it's my property and I should be able to do whatever I want, despite the fact that laws and judicial rulings supporting building regulations, zoning, and historic preservation are long standing (see the comment thread in response to the City Paper article "Anything Worth Saving Here?: H St. Rowhouses Edition" for examples of this); or

-- "old places where George Washington hasn't ever been can hardly be considered historic." (Another variant would be "just because it's old doesn't mean that it's historic."

There is an article in the New York Times, "Challenge to Landmark Law Worries Preservationists," about the challenge to the City of Chicago historic preservation laws by a local realtor as an example of the latter type of thinking, which is not unique to Chicago.

If you work on historic preservation issues anywhere, it usually comes up, especially in the context of historic districts, where individual buildings are protected, even if most don't exhibit characteristics comparable to the level required for designating an individual landmark.

Part of the problem has to do with people employing different frames of reference simultaneously, in what a professor would deem as an illogical construction. I happen to be dealing with this in regards to a matter in the DC side of the Takoma Park commercial district, and here is an extract from some writing about it.

-----

In getting an A- and not an A in my freshman level European history course, in talking to the professor who went over my exam w/me to explain my grade, he said I didn't answer the question properly. The question was to compare the relative stability in Europe at the beginning of the medieval era (beginning of the period covered by the class), to the reformation era (end of class). I did so, but then took the question beyond, and compared the Reformation era level of stability to the "today" circa late 1970s. He said that wasn't the question, that my final comparison was made against a totally different frame of reference, one outside of the question.

The issue with the preservation of districts is more about the vernacular, about what I call the nexus of place, architecture and people (history). That's what we're dealing with here. The CFR regulation language wrt the National Register is:

(d) District. A district is a geographically definable area, urban or rural, possessing a significant concentration, linkage, or continuity of sites, buildings, structures, or objects united by past events or aesthetically by plan or physical development. A district may also comprise individual elements separated geographically but linked by association or history. (36CFR60)

The criteria for buildings ("contributing resources") in districts is not as stringent as the criteria for landmarks. But that doesn't mean that the buildings aren't important, or that the principles of preservation are easily discarded. Furthermore, the point of a preservation group such as a Main Street commercial district revitalization organization or a neighborhood historical society and other similar organizations is to work harder than the average person or organization in the furtherance of the broad principles and actions of preservation.

Of course simple art deco commercial buildings in Takoma aren't New York City's Chrysler Building, but that isn't the standard on which they are to be judged. Part of the significance of the commercial district is in how it shows changes as the community changed, as the commercial district modified in response to first the streetcar and then the automobile, away from the railroad, around which the community was first developed.

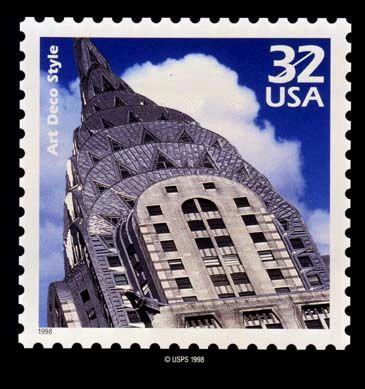

The Chrysler Building, New York City, is used as the ultimate example of art deco architectural style on this postage stamp.

And with art deco, there are many gradations of the style, all of which are recognized as being a part of the broad style. There is no question that this commercial building in Takoma is simple, extremely simple, by comparison to landmark quality buildings. But simplicity, just like for my bungalow, isn't something to hold against the building, and nor is it justification for making potentially significant changes to the character of building.

The argument of simplicity as a reason to justify significant change can be laid against any building within Takoma Park, if it ends up being compared to buildings outside of Takoma that exemplify the most complete and superior examples of particular architectural forms and styles. A Victorian house will always be outshown by Victorians in Newport, Rhode Island, an art deco building will be outshown by the Chrysler Building, or hotels in Miami Beach, a theater in a neighborhood like Takoma will be outshown by finer, better examples somewhere else.

So why bother to preserve anything? There are always better examples, and this is only significant then within the neighborhood, right?

But that isn't the question when it comes to the characteristics of preservation in the context of historic districts.

Rather than ride the slippery slope, my general inclination is to recommend against significant changes to the buildings and their outward appearances, and to make judgements and evaluations of the buildings within the context of the Takoma historic district and the Takoma commercial district, and the general architectural styles exhibited by the buildings.

----

Or as the Post editorializes:

But what ultimately determines if a site is designated as historic should be whether it is historic, not who owns it.

And let's be sure we are asking the right questions and using the proper frame of reference when we are deciding what is historic and what isn't.

Labels: cultural heritage/tourism, cultural planning, historic preservation, historiography, urban history

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home