A focus on city greatness via transit (and placemaking) waxes and wanes depending on who is elected

Toronto has had a very ambitious agenda for transit expansion called "Transit City," with the basic principle that no one should be disadvantaged by not owning a car.

Because subway (heavy rail) is very costly, it requires a great deal of ridership to justify expansion. As Toronto has developed outwardly ("sprawl", exurban development), it is less efficacious to extend subway lines to distant places--this is the same argument made by Belmont in Cities in Full when he discusses polycentric vs. monocentric patterns of transit networks, and his criticism that for the most part extending subway networks outward supports sprawl rather than constrains it. So the Transit City program focuses on light rail and other surface transit improvements, rather than subway expansion.

There has been some opposition to the putting light rail on the proposed Purple Line, which will connect Bethesda and New Carrollton, providing an east-west circumferential connection between the red, green, and orange subway lines in Montgomery and Prince George's Counties in Maryland, because people argued for an interoperable heavy rail system (the Metro subway line). But even though the Purple Line is likely to have high ridership, as much as 70,000 daily riders, this high ridership isn't enough to justify heavy rail over an 18 mile distance.

Governing Magazine has an important article, "The Search for Infrastructure-Driven Transformation: Where's the next Erie Canal?," on breakthrough infrastructure projects that boost local and regional economies. From the article:

The Erie Canal is usually characterized as America’s first great infrastructure project -- but it was much more than that. It was America’s first great economic development effort. ... When we think of economic development, we don’t always think of the transformational infrastructure project. We think of recruiting businesses and factories. Or we imagine nurturing the ecosystem of researchers, educators, entrepreneurs and financiers. Repeatedly throughout history, however, Americans have turned to infrastructure to stimulate economic development. And at a time when voters are resistant to higher taxes and skeptical about subsidies to business, they remain enthusiastic about building big infrastructure projects. ...

The American Recovery and Reinvestment Act was heavily tilted toward capital projects on the theory that “shovel-ready” projects could put people back to work -- mostly for private contractors rather than government agencies. The Barack Obama administration is also using federal transportation money to promote “placemaking” -- the creation of parks, plazas and squares that attract people in addition to simply improving travel. In California -- a state that’s perpetually bankrupt -- state and local voters regularly resist taxes, but constantly vote in favor of multibillion-dollar bond issues for schools, parks, roads and even affordable housing. So if we’re going to make big progress on the economic development front in the near future, we’re probably going to have to do it by leveraging big infrastructure.

However, the record on using big infrastructure for economic development is decidedly mixed. ... wherever there’s big infrastructure there’s also big pork. State and federal funding for infrastructure projects is rarely distributed with long-term economic transformation in mind. Short-term political benefit is usually the order of the day.

The challenge facing state and local government today is not merely to spend money on infrastructure, but to spend that money in a way that will foster economic development. Economic development leaders often approach this in a one-off way -- an off-ramp, rail spur or property that benefits a business they’re trying to attract. Such an approach may help a specific business, and in turn, help the community. But it’s not likely to lead to transformative economic development efforts.

Transformative efforts are usually systemwide, and they generally do one of three things:

• Make it easier to move goods and people, as the Erie Canal, Transcontinental Railroad and interstate highway system did.

• Make it easier to move information vital to commerce. Think of the telegraph, telephone and Internet.

• Radically reduce the cost of doing business -- or alternatively, greatly increase the capacity to do business. The introduction of electricity as well as the Internet served both of these purposes.

Of the many infrastructure investments on the table today in the United States, only a few serve any of these three purposes.

There are at least four examples of transit projects being actively opposed and/or dumped with a change in political leadership:

1. Hudson River Tunnel connecting New Jersey and New York City, providing an additional connection to Grand Central Station, cancelled because of action by New Jersey Governor Christie. Although note that transit advocates argued that there were problems with the project as it was conceived by New Jersey Transit and now there is an alternative proposal to extend the #7 subway line to New Jersey, which won't provide additional railroad passenger capacity. (See "Planned Hudson River rail tunnel isn't perfect, but it's good" from the Newark Star-Ledger and the letter to the editor by the Chairman of the National Corridors Initiative in the New York Times).

2. The new Mayor of Toronto calling for surface transit improvements in the Transit City program to be dumped in favor of subway-only expansion. ("‘War on the car is over’: Ford moves transit underground" and "Hume: Ford to Transit City: Drop dead" from the Toronto Star, although the Mayor can't make such an executive decision, especially as much of the money for the transit improvements come from the Province of Ontario)

3. Repudiation by newly elected officials in Wisconsin and elsewhere of previous commitments to high speed rail projects. Although nearby states committed to high speed rail see these rejections as a funding opportunity, e.g., "Illinois' high-speed rail hopes raised" from the Rockford (IL) Register-Star.

4. The continual opposition to streetcars in DC, frequently criticized as being not a 21st century mobility technology--when the reality is that technically, automobiles too are a 19th century technology, and a general ignorance about the general principles of optimal mobility, especially in terms of their application to center cities as opposed to the suburbs.

(You could even consider the constant back and forth in Seattle over how to deal with the Highway 99 Viaduct and whether or not to tunnel it to be somewhat related, although it is a road project first and foremost.)

I think what links these various actions is a failure to have a general philosophy and consensus of what builds and strengthens local economies, the failure to understand the concept of placemaking, the failure to understand what works and what doesn't in terms of optimal mobility, the failure to understand that cities have different needs and opportunities than the suburbs (e.g., Christopher Hume's column, "Hume: Why the 905 needs Rob Ford" making the point that Toronto's new Mayor is in the wrong place, that he should be a mayor in a suburban community), and the failure in the case of NJ and WI about how certain types of transportation investments strenthen regional economies, not to mention the failure to understand the concept of resiliency and building alternative transportation modalities (i.e., trains vs. planes).

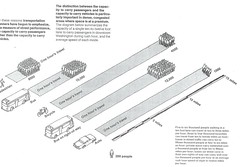

19th Century vs. 20th Century Street Design, Central Washington Transportation and Civic Design Study, 1977. This image puts into better perspective 19th Century vs. 20th/21st century transportation technologies and the negative impact of the latter on urban quality of life for residents and neighborhoods.

While the Obama Administration has made some placemaking-related breakthroughs in terms of linking the agenda of agencies like HUD, EPA, and DOT, this policy has the same endemic failures that the Obama Administration has made with regard to health care policy and the warding off of a major Depression--they haven't communicated what these policies mean and why to the average citizen, they haven't built from a more ground up perspective what these policies mean to the health and well being and future success of the nation and its regions.

And like how the Pharmaceutical and Health Care industries poured tens of millions of dollars into the pro-Republican political advertising campaign developed by the the U.S. Chamber of Commerce, industry not to mention everyday people who can't understand any way of getting around other than the automobile, are pretty much united about keeping land use and transportation paradigms the same.

We're in the midst of a multi-decade slog on changing overall behavior and understanding, and clearly we have a long way to go. But not having made very clear what those principles are and debating it makes it that much harder.

Labels: building a local economy, economic development, electoral politics and influence, transit and economic development, urban design/placemaking, urban revitalization

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home