The process of reinvestment described in the "gentefication" process is similar to the way some immigrants continue to invest in their old communities as described in Arrival City by Doug Saunders as well as many articles in the media (I can think of articles from the Los Angeles Times and the Washington Post and the New York Times specifically) about how Latino immigrants in the U.S. invest in their communities "back home" and how this changes those communities. It's just a matter of focusing that investment on "arrival neighborhoods" in the U.S. instead of back "home." And it's just a scalar difference from earning money abroad and sending it home to the family--economists call it "currency transfers."

Two things that make the discussion of gentrification difficult in the US concern how people still tend to (1) believe that living in cities is undesirable and is counter to most trends concerning residential choice; and (2) ignore class/economic distinctions, or make sweeping generalizations about them, thinking that most people of color (African-American and Latino in particular) are poor.

They also don't think much about the fact that the US is decidedly a market economy, albeit with plenty of government intervention in the housing market (both policy and financial), and for areas in demand or areas that become more attractive, good deals/low prices lead to increased demand, and in situations with increased demand, people with more money win out over people with less money.

Just like how some people believe that only white people can be racist (not true), others believe that only white people moving into center city neighborhoods are "gentrifiers."

By thinking this way, what they fail to appreciate is that the process of in-migration of this type is about money and class, not race.

-------------------------

This excerpt from

a past blog entry is about 7 years old:

Gentrification effect (2) is what I think people really mean when they are talking about "gentrification," new and different people coming into a neighborhood. Of course, in neighborhoods like CH, displacement is really happening.

As far as displacement goes, it's part of what people call "gentrification". But gentrification is phenomenon with multiple effects, which I describe as:

(1) new investment in a previously underinvested area;

(2) change and different people coming into a neighborhood -- most importantly, different people from those currently in residence (the differences--race, class, ethnicity, levels of educational attainment, attitudes toward the urban experience, etc.--are usually not "celebrated" (I make this point because I still remember first being taught about diversity and multiculturalism in 7th grade, and I specifically remember the "melting pot" and "celebration of differences" phrase -- I have a hard time seeing the celebration, at least in DC);

(3) increase in conversion of previously rented dwellings to owner-occupied, leading to a displacement of renters and an overall reduction of the number of rental units available in the neighborhood;

(4) related to the new demand for living in the neighborhood is an increase in rental rates, which contributes to the displacement of low- and moderate-income residents;

(5) neighborhood improvement as investment (primarily through the renovation and sale of houses to new residents) continues to increase and begins approaching critical mass (cf. Goetze

Building Neighborhood Confidence);

(6) faux-displacement as long-time residents decide to "cash out" and take profits on the sale of the finally appreciated property (this is accelerated by, in my opinion, the still prevalent pro-suburban, anti-city attitudes embraced by particular demographics that tend to represent the long time population groups in traditional center cities); and

(7) ongoing increases in property tax assessments which contributes to the displacement of longtime residents on fixed or lower incomes (note that this effect is hard to separate out from [6]).

------------------------

While the academic study of gentrification focuses on national and global processes of "the reproduction of space" rather than seeing gentrification as mostly an issue of race, I still believe that the urban sociology subfield of gentrification in the U.S. has one major flaw, that the cycle of urban development should go only one way--outward, and that neighborhoods are born; grow; and decline, and in the declining phase become home to the less well off; rather than recognize that decline is not inevitable when considering multi-decade time frames.

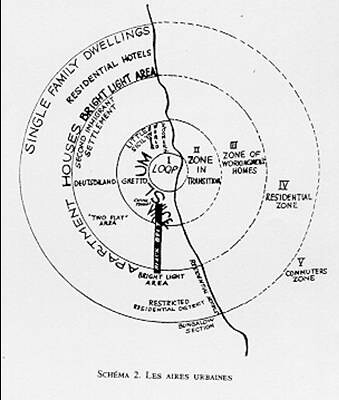

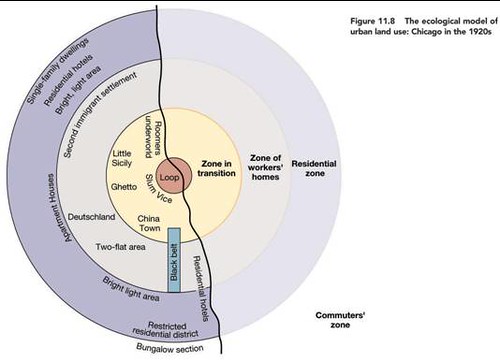

This is based on the 1920s work of the "Chicago School of urban sociologists," in particular Robert Park and

Ernest Burgess. Their work was based on the idea that the well off wanted to be separate from the less well off and so they continually moved outward from the core of the city.

As neighborhoods were "abandoned" by groups as their economic situation improved, they were replaced by new immigrants and in-migrants and the process began again. This process has a number of terms to describe it, including invasion-succession theory, ecological succession, or

concentric zone theory. And the 1970s housing improvement theory called "filtration" is based on this idea as well.

The first diagram is from The City by Park and Burgess, the second is a more modern rendition and might be easier to read.

Much of the study of gentrification over the past 30 years is based on the work of geographer Neal Smith and his book

New Urban Frontier: Gentrification and the Revanchist City. Other work that I like (Loretta Lees' Gentrification, co-authored with Elvyn Wyly and Tom Slater, and her paper in

Urban Studies Journal, "

Super-gentrification: The Case of Brooklyn Heights, New York City") utilizes a similar thesis, that inner city communities, usually minority, are underinvested and this allows people with higher incomes and power to acquire property transform space, and displace the less advantaged.

The supergentrification thesis is subtly different and very much relevant to global cities. It's about how people with extranormal income, such as Wall Street financial types, reshape the market for residential real estate in desirable submarkets like Brooklyn Heights. This idea can be extended to the idea of second, third, and fourth homes in desirable cities such as Charleston, SC, Downtown Washington, South Beach in Miami Beach, San Francisco, etc.

Locals are displaced by capital flows from outside the region. Capital flows from outside the region are shaping the DC housing market at many levels.

I think what's happening in California in Latino communities is different from what's happening in Anacostia. African-Americans of means moving to Anacostia for the most part don't have previous connections to the neighborhood, unlike the Latinos profiled in the SCPR piece.

The back to the city phenomenon on the part of African-Americans is still a pretty localized phenomenon and counter even so to the multi-decade out-migration of middle class and upper middle class blacks from DC, especially to Prince George's County (and from there to Charles and Anne Arundel Counties).

My sense is that those African-Americans in-migrants who do want to live in the city are being priced out of more desirable areas and are picking Anacostia as a result. (Very much like how I chose to buy a house in the H Street NE neighborhood in 1988--although I don't live there now. Then, prices throughout the city were constantly rising, the H Street neighborhood was seen as less desirable so prices were much lower, although it was close just as close to Downtown as Capitol Hill with comparable--but smaller--housing stock date from the 1880s to the 1920s, and I thought if we didn't buy then we'd be forever priced out of the market.)

I do think as Anacostia improves and becomes more safe, it's possible that the in-migration of whites and Latinos could make the market even more competitive and over very long frames of time, the area could experience significant non-African-American in-migration.

---------------

To those of us who have been in the city for 20+ or more years, and lived in areas seen once as undesirable, we know this is a distinct possibility. I talk with my next door neighbors--they are lifelong Washingtonians and in their 60s--and we are all amazed at "seeing white people" and baby carriages or bicyclists on various blocks, say the 600 block of Orleans Place NE, which in the late 1980s was one of the city's chief distribution centers for crack and the location of dozens of murders over that time, or at 1st and M Street NW, etc.

This was completely unimaginable even 10 years ago.

----------------

Although it's probably a 30+ year process--it will take that long for significant redevelopment to occur east of the Anacostia River because it will take 20 years or so for more desirable parcels located west of the river in SE, SW, and NW to be developed although places located on subway lines will be absorbed first (Capitol Riverfront, Southwest Waterfront and Southwest, NoMA, Reservation 13, McMillan Reservoir, areas near transit stations such as Fort Totten and Brookland, and parcels near Rhode Island Metro, Takoma, the Armed Forces Retirement Home, H Street NE, lower U Street, Walter Reed, etc.).

This could speed up a bit if a more concerted effort to link the Capitol Riverfront development west of the river with the development opportunities at Poplar Point east of the river in a joint revitalization planning process and program occurs.

I think that could have more positive effect than the focus on the St. Elizabeths Campus, which is pretty much self-contained (see the old blog entry from 2006 "

Enclave development won't save Anacostia") and therefore has less capability to generate "trickle down" and "trickle up" improvements.

But the point of the academic literature on gentrification is that the poor are displaced. New investment doesn't help the less advantaged all that much.

But cities need investment and in-migration in order to thrive. So the reflexive oppositional stance vis-a-vis in-migration and investment is counterproductive, at least if you want to have the money to pay for public safety, quality schools, and other municipal services.

David Harvey's paper (expanded into a book), "

The Right to the City," first a lecture then published in

New Left Review, makes the point that the right to the city is imbued in us as citizens, and transcends our place as defined by the market economy.

In a market economy, for this to be the case, Social Darwinism as the predominate social policy has to be supplanted by a much broader agenda, which in a time of economic privation, it's very difficult to find proponents for such an agenda.

Frankly, I don't think the issue should be preserving places for the poor as they are as much as it should be on assisting people so that through education, training, and other assistance, they are prepared, able and capable of participating in the market economy. I can't claim to have a particularly good set of policy proscriptions to do that although I have a bunch of ideas:

- a robust affordable housing policy and a robust program to maintain affordable housing stock through portfolio investment programs, new production of affordable housing, community land trusts, and cooperative housing programs

- great public schools

- year round school, extended day programs, co-operative high school programs

- caseworkers assigned not to multiple families but having one or two families only as their clients (think of what this article discusses on routinization of positive health behaviors and apply it to participation in the market economy, "

Gentle Nudges Work to Get People Exercising," from the

Wall Street Journal).

Until we take this step, in-migration into the city and the process of improving and repositioning neighborhoods will continue to be traumatic and contested.

1 Comments:

I liked the test and the site very much. thanks.

Post a Comment

<< Home