2. Of course, one thing holding up the economy is the increase in credit standards for mortgage holders, which is preventing many mortgagees from refinancing, even though they are current on their loans, but could reduce the cost of monthly payments, given the extremely low interest rates at present. See the editorial "

An Easier Path to Refinancing" from the

New York Times.

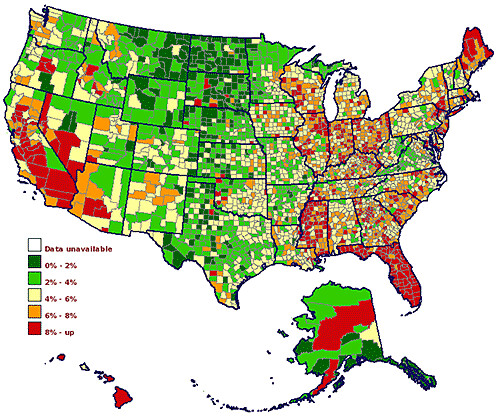

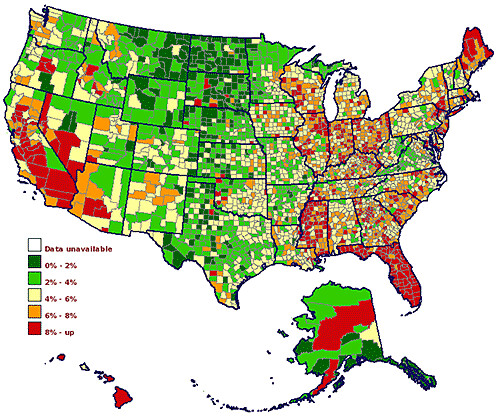

3. But so much of the U.S. economy has been built on mass production of housing farther and farther from the core of regions that this will require significant changes in how our economy functions.

In weak market cities, where sprawl-oriented housing production made inner city housing location worthless--Rolf Goetze pointed out in Understanding Neighborhood Change, published in 1979, that significant production of new suburban housing in excess of normal demand produced these conditions.

But changes will take decades to work through the system.

--

Washington Post photo gallery from October 2011 on Cleveland's housing demolition programThe reason that I often react so negatively to these kinds of programs is not necessarily this practice in weak markets, but because reflexively officials in other areas start saying that these are good programs, for places where the conditions are different, e.g., Baltimore, if their property taxes weren't so high, and there was a true urban growth boundary in place, ought to be able to recapture households for many of the areas that are otherwise blighted today.

The real issue is disinvestment. What people call "blight" is a result of disinvestment. Rather than blame the place (I call this "blaming the building"), focus on disinvestment and explain the process.

Buildings or neighborhoods called dilapidated, run-down, blight(ed), eyesores, nuisances, decrepit, (etc.) are victims (and survivors) of disinvestment.

Too often people are lulled into believing that demolition, especially of historic buildings, is a solution to "blight" when merely it creates a different form of blight, one that is harder and usually more expensive to correct (building a new building).

The solution to disinvestment is not demolition, but investment .

And maintenance and/orrehabilitation is the proper response to neglect or demolition-by-neglecy.

The funny thing is that many DC neighborhoods, while not exactly quite to the point of neighborhoods in Cleveland--the Cleveland Metropolitan area has expanded greatly, but over 50 years, the area's population hasn't increased significantly, it's just that hundreds of thousands of people have moved from Cleveland to the suburbs--were seen as not fully recoverable, as recently as 2003. Now these neighborhoods have houses selling for in excess of $800,000 (if only I had kept my house...).

But at the same time, historic designation is another way to re-value neighborhoods and the properties within them, so it is an important neighborhood and center city revitalization strategy, especially in weak markets.

Although in weak markets, the extra costs associated with maintaining houses to historic guidelines often can't be captured in higher values, which is another conundrum.

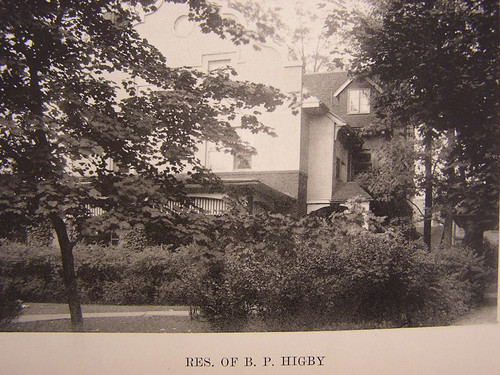

This house, the Lyons House, in the Wick Park Historic District in Youngstown, Ohio (one of the first cities in the U.S. to begin planning for contraction with the Youngstown 2010 initiative, which started in the late 1990s or very early in the last decade, because I knew about it in 2001), is available for $15,000, but will require a significant amount of money for rehabilitation. See "

This Old House features historic Youngstown home in its March issue" from

Metro Monthly (which is the source of the photo also).

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home