It ain't true: chain retailers are entering the city, but not necessarily on the city's terms

The New York Times has a story today, "Retailers' Idea: Think Smaller in Urban Push," about how because center cities--after experiencing decline for decades are now (re)experiencing population growth, most importantly, population growth generated by higher income and younger demographics--find that chain retailers, after focusing on the suburbs for decades, are now re-entering the city.

From the article:

Retailers are now willing to come into cities on the cities’ terms — with all the zoning headaches, high rents and odd architecture — because that is where the growth is. Most large American cities are growing faster than their suburbs for the first time in almost a century, according to a Brookings Institution analysis of census results released last month, largely because young adults are choosing urban apartment life. That population shift, along with Internet competition, have made the car-focused, big-box model less relevant.

I just don't know if I believe this.

Chains are coming into the city and dealing with zoning and rents.

But for the most part, they are still focused on fitting their standard formats, developed for suburban locations, into the city, with minimal substantive changes.

There are exceptions. But there aren't enough exceptions to see a pattern that supports the assertion that "retailers are now coming into cities on the cities' terms."

The urban push by retailers makes even more apparent the need for special big box review ordinances/zoning procedures/zoning regulations

Plus, the New York Times story doesn't discuss some of the hardcore "rolling up" of elected officials to ease the entry of chains, in particular Walmart, in many urban markets. The ability to better shape Walmart's entry into DC was absolutely constrained by Walmart's strategic lining up of the support of key elected officials, from the mayor on down, before their public announcements.

DC lacks a big box retail review ordinance and because elected officials jumped on the Walmart bandwagon fast and furious (see "The Selling of Walmart: How the world's biggest retailer won over D.C. without a fight" from the Washington City Paper) it became almost impossible to develop any forward momentum to deal with Walmart from a position of oppositional strength, in the situations where the developers needed that kind of push in order to do better projects. (There was a movement to create "a community benefits agreement" with the company, but nothing in the zoning laws requires such agreements generally, although for two of the sites, such agreements will be triggered, but for those sites only.)

No ability to push back on the developer and/or the company means the projects for the most part won't improve (a/k/a "suck").

And I would argue it's a dereliction of the responsibilities of elected officials to act solely as cheerleaders and not as "organizers" focused on achieving the best possible outcome to the city and its constituent neighborhoods.

Although even when there are zoning procedures in place that the companies don't like, companies may work very hard to overturn them or to win special exceptions from the laws being applied.

San Diego passed a very strong big box review ordinance. I haven't been able to find the exact legislation ("Ordinance to Protect Small and Neighborhood Businesses"), but this report on the bill by the San Diego Office of Planning has a good overview of the provisions.

But massive organized opposition by Walmart led to the City Council caving, and repealing the ordinance. See "City Council Votes To Repeal Big-Box Ordinance" from San Diego Channel 10 News.

But from the standpoint of a well planned and prepared city, the San Diego ordinance is exactly the kind of retail review ordinance that center cities need to have in place in order to deal with these kinds of projects, if you want to be able to have leverage for negotiation.

Home Depot

For example, you have a very suburban style big box Home Depot in DC.

Yet you have a Home Depot in Manhattan located in a historic building that was once a department store, and the store does home delivery.

Flickr photo by Mattron. Caption: Stern Brothers was New York's largest department store of the 19th century. This magnificent cast-iron building was their flagship location from 1892. Now a rather convenient Home Depot.

And you have a Home Depot in Chicago integrated into a neighborhood commercial district.

Home Depot on South Halsted Street in the Lincoln Park neighborhood of Chicago. Photo by Steve Pinkus.

But you don't see a pattern yet of Home Depot integrating their stores into urban settings and offering delivery in a systematic way in a manner that we would consider decidedly urban.

Walmart

Similarly, with Walmart's foray into DC, 2 of the 6 stores -- that's 33% -- will be components of mixed use multistory buildings. The other 4 stores will be part of projects that are either single site/no mixed use or more suburban styled shopping centers.

Although in other cities, Walmart is experimenting with a variety of formats, smaller supercenters, stores styled more like convenience stores, but larger, modeled on the so far unsuccessful Fresh&Easy West Coast initiative by Tesco, and supermarket only stores called Neighborhood Markets.

While a typical Walmart store's sales are 55% food, with a population of slightly more than 600,000, and with limited reasons for nonresidents to come to DC to shop, 6 stores seems to be 2 too many for this market.

In fact, two of stores will be within 2 miles of each other, which is likely the only such example of Walmart supercenters being located so close together out of the entire US store portfolio. (Although two of the stores will likely get some business from Prince George's County residents, as the city-county line is less than one half mile away from each of the proposed locations.)

Note that this Walmart Neighborhood Market store in Chicago is not part of a vertical mixed use project (and the same goes for the new City Target in Seattle).

Target

Target as of yesterday opened their first "City Target" in Seattle, which I wrote about earlier this week. It will be interesting to see if this store format--about 1/3 smaller than a typical suburban Target, with a smaller selection of products, including fewer larger sizes, and maybe no lawn mowers--influences the company and their store organization and format in other ways in other locations. (The Times story says that Target also opened City Targets yesterday in Los Angeles and Chicago.)

There is no question that the City Target model is shaped by the company's experience with their foray into DC's Columbia Heights neighborhood, as the main anchor of the DC/USA project on 14th Street NW. It's an all retail building (no theaters, unlike the Harlem/USA project in NYC on which the project was modeled), with a lot of parking--half of it unused, at a great expense to the city--and a store size comparable to the company's suburban stores.

New City Target in Seattle, note the open windows. Over the past few decades, large format retailers have shifted away from stores with windows, to focus customer attention on the products inside the store. This store is an exception. Seattle PI photo by Sofia Jaramillo.

Supermarkets

In Canada, the Sobey's chain has a variety of formats including some stores specifically designed for the center city market. I've written about them but this Toronto Globe & Mail piece, "How Sobey's is taking on Loblaws" is more definitive. (This blog entry "Revisiting Sobeys Urban Fresh," from Only Here for the Food describes a Sobeys store in Downtown Edmonton.)

In the US, while supermarkets are locating in the city, they are still internally focused, even if the companies are doing different things. I've written about this issue in the blog for years ("Urban supermarkets and urban design") but also in an op-ed in the Washington Business Journal, "Urban Safeway Design Misses Mark."

In the DC market, Harris Teeter and Safeway are opening up stores as part of vertical mixed use projects, with structured parking, in both the city and the suburbs. Harris Teeter has a big focus on prepared foods, while Safeway does not. Giant, a lagging chain in DC proper, although still strong but under pressure in the suburbs will be opening three stores (one is new, the others are redevelopments) in vertical mixed use projects.

Whole Foods is the only store that does merchandise the front of the building somewhat more towards the ways I've suggested in past writings.

The Whole Foods Market in the Foggy Bottom neighborhood (pictured above) has a separate entrance and set up for prepared foods, which takes the sale and eat-in/on premises of prepared foods to a new level for a typical urban located supermarket, more towards the ways I've suggested in the past, to a level beyond Harris-Teeter (or the former Ukrops chain in Richmond) or Wegmans, which has extensive inside eat-in options (Whole Foods does at some of its newer suburban locations), but not outdoor patios and the like.

Pharmacies

Walgreens purchase of New York City's Duane-Reade chain has significantly influenced changes in store formats, which I have written about in the past, ranging from a super-duper store on Wall Street that includes a shoe salon, sushi, self-serve yogurt, a high end selection of business periodicals, and other services. to selling draft beer at a location in Brooklyn. And this has begun to influence store formats outside of New York City--at least in Chicago--but not anywhere else in the Walgreens chain as of yet.

Walgreen Drug Store on Canal Street in New Orleans. Note that the windows are covered up, although the store remains in a historic building. I don't know if the upper stories of the building are in active use. Flickr photo by army.arch.

For the most part, even in the cities the big drug store chains, including Walgreens, prefer to build their standard format store, originally designed for suburban locations, with drive throughs and big parking lots, as a single story, non-mixed use building, except in downtowns, where they lease ground floor locations that are part of office or apartment buildings.

Office supplies

The Times story mentions Office Depot opening smaller stores in central business districts. Staples is doing the same thing. But for the most part, this is a logical and easy thing for the companies to do, because compared to the other formats, their stores are smaller anyway.

The smaller format makes sense because central business districts are where office supplies are consumed the most anyway, and while the array of products offered compared to a typical suburban location may be constrained, business customers are accustomed to ordering products like desks from catalogs anyway.

Conclusion: Temper the glee

Also in the Washington Business Journal, I wrote an op-ed about the Walmart foray into DC, "Temper Walmart Glee with Planning," that made the point that we shouldn't be cheerleaders, but act towards the entry into the city by big box retailers with both open eyes and open minds, and with the right regulatory review protocols already in place.

Dealing with large format stores isn't unique.

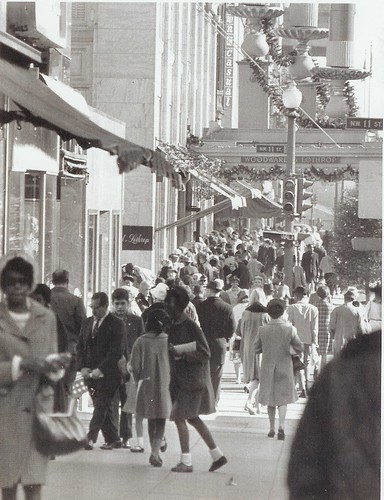

Very large department stores once ruled the cities.

11th and F Streets NW, Washington, DC, December 1968. Photo source unknown.

The issue is to reshape the suburban-oriented formats of today's large retailers into ways that are more in concert with urban needs--the desire to promote vitality on city streets instead of dead zones and the desire to integrate retail into already extant places and reviving them, rather than building new retail on greenfield or grayfield locations that still requires an automobile trip to the store and back.

Without acknowledging these issues, the New York Times article misses at least half the story.

Labels: big box retail ordinances, commercial district revitalization, commercial district revitalization planning, formula retail, real estate development, retail planning, urban design/placemaking

1 Comments:

very interesting blog,nice information.your work is very excellent.

Post a Comment

<< Home