Hampton Roads-Virginia Beach Kings professional basketball team

So there are reports ("Va. Beach board has spent nearly $700,000 in effort to get arena" from the Norfolk Virginian-Pilot among others) that Virginia Beach, Virginia is looking to build an arena and land a professional basketball team, perhaps the Sacramento Kings.

Now, as discussed in yesterday's entry about the success of the Chicago Cubs vs. the Chicago White Sox, which I ascribed to the place values of their respective venues (but commenter Alex B. made the counter point that the Cubs also have a larger fan base and more engaged fans), I do admit that while professional sports aren't particularly good for metropolitan economies generally--if you don't spend money on sports tickets you spend it on something else and vice versa--there is no question that some sports have more positive impact than others, and depending how the arena-stadium is sited and integrated into a community, a sports venue can contribute either positively or negatively to other urban revitalization and economic objectives.

We can argue about the nature of the Atlantic Yards project in Brooklyn more generally, but even so there is no question that a basketball arena there will have much more positive effect and will be incredibly well served by transit, compared to an outlying suburban location.

Same with the impact of the Washington Wizards and Capitals sports teams, playing in an arena in Downtown DC--also well served by transit--versus playing in their former suburban location unconnected to other commercial areas and mostly reached by automobile.

RFK Stadium in DC is a good example of how not to locate a sports stadium within a city, and there are other examples across the country, of how sports stadiums can be positive or negative, depending on the type of sport and how the stadium/arena connects to the city around it. (Suburban locations pretty much fail generally, although the arena for the Anaheim Ducks hockey team anchors a small commercial area.)

I've written about the Sacramento Kings a bunch this year in terms of the quest by Sacramento Mayor Kevin Johnson (an ex-basketball player) to build a new arena for the team, and to get the team's commitment to paying towards the new arena ("Stadiums and arenas and funding: Sacramento and Seattle edition"). Part of the desire for the arena is to further spark downtown redevelopment.

But the scary thing is that even successful teams like the Phoenix Coyotes hockey team--they were Western Conference finalists this year -- may require municipal subsidy. Right now, the city of Glendale, Arizona is paying $25 million per year to keep the team in their city.

But compared to other "major league communities," the Sacramento metropolitan area is comparatively small in terms of population, plus it's been devastated by the real estate crash, so housing values, property taxes, and other revenues have dropped precipitously.

Even so, the Sacramento Metropolitan Area is 60% bigger than the Hampton Roads Metropolitan Area and has a higher median household income, and while Hampton Roads is more economically viable compared to some of the smaller areas with teams such as Oklahoma City and Jacksonville ("A richer region means better odds for the NBA" from the Virginian-Pilot), the area has economic issues of its own, facing almost certain decline as military budgets shrink, as the regional economy is dependent on spending on military bases and ship construction, and sea levels rise with global warming.

Anyway, after all the scrambling by Mayor Johnson, the Sacramento Kings team pulled out of the deal. See "Maloofs, city leaders lacking trust" from ESPN and "Maloofs doubted AEG revenue estimate in spurning Sacramento arena," from the Sacramento Bee.

That would make me extremely leery, were I a government official in another locale, in dealing with them (not to mention the one Maloof lady on "Real Housewives of Beverly Hills"). In addition to the general difficulties of pulling together a deal of course. From "Va. Beach mayor: Arena could cost $275M to $400M" in the Norfolk Virginian-Pilot:

Sessoms said the city could not build it without financial help from the company, the state and the NBA.

"I would assume from out of those three, there's got to be some cash," he said, adding that he was told by Comcast-Spectacor representatives that revenue generated by the arena would pay debt service on any city funding for the project.

Several state programs could provide financial assistance.

Gov. Bob McDonnell recently offered a $4 million performance grant to the Washington Redskins as part of a $6.4 million public package to keep the NFL team's headquarters in Loudoun County and establish a summer training facility in Richmond.

If larger sums are needed for the proposed Virginia Beach project, industrial development authorities and the Virginia Public Building Authority are options. Both have the capacity to issue debt for substantial development projects.

In addition, Virginia law gives certain localities, including Virginia Beach, authority to retain some sales tax revenue collected at a facility that is a joint public-private venture - such as a sports stadium - to pay off construction debt.

Plus, the place where the Virginia Beach proposes to put the arena, next to the Convention Center, is in an outlying part of the city, where there are limited opportunities spillover benefits--e.g., the way that the Gallery Place area is filling out, with the Verizon Center being a key anchor, or how the Capitol Riverfront area is developing--although the plans predated the Washington Nationals stadium, there is no question that the ballpark is an anchor and a significant contributor to the neighborhood's branding as a place to live and visit.

.... although that location would likely be served by light rail, if the Tide light rail system is extended to Virginia Beach (past blog entry "Light rail in Norfolk, Virginia and suburban Washington, DC").

Then again, maybe the Sacramento Kings ownership group--the Maloofs--are bored with Sacramento and want to move, or figure they can sell out for a higher price to a more motivated group interested in moving the team.

Politics versus governance and handling sports teams and arena-stadium funding decisions

Okay, so my general position is that local and state governments shouldn't be funding sports teams and venues, because there is much greater economic return from spending on different kinds of programs and revitalization initiatives (especially transit).

But from an advocacy standpoint, do you just take the "no, no, no" position, when in the end the team will be landed and the venue will get public funding anyway?

Is it better from a "governance" perspective, to work on making the deal better or at least "less worse" from the public standpoint?

I think so. Therefore I offer the following as a set of recommendations to start the development of a more general agenda/set of positions on such questions, with the aim of advocates and public officials using such a checklist as a way to shape their agenda and negotiations on such projects going forward.

Stadium/arena placement, design, and mitigation

1. One of the most important decisions concerns placing the venue in the right location so that there will be additional positive economic and urban revitalization benefits, rather than expecting trickle down benefits to happen magically.

Urban revitalization and historic preservation consultant Don Rypkema argues that the economic benefits of stadiums/arenas typically peter out after 1.5 blocks. If we are purposeful about linkage, leveraging, and investing in improvements before the facility opens, rather than a decade later (like around the DC Convention Center), I think the improvement zone impact from such venues can be significantly expanded and enhanced.

SBC Park opened in 2000 as Pacific Bell Park. By far the most breathtaking of the 18 major league ballparks that have opened since 1989, it glories in its tight perch between a big city and a wide-open bay. SF Chronicle photo by Michael Macor.

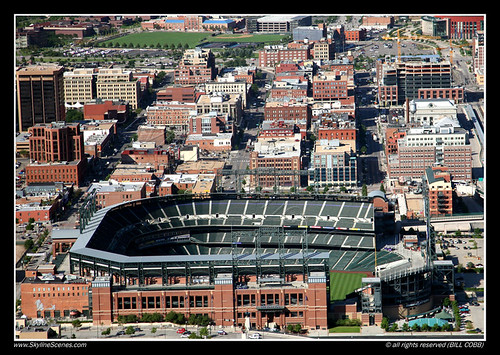

Coors Field in LoDo, Denver by SkylineScenes, on Flickr.

2. Achieving the "Camden Yards" effect (although I argue that Camden Yards doesn't do all that it could do, at least it is adjacent to Downtown Baltimore). Building a facility with the right urban design qualities is essential (past blog entry, "Tale of Two (or more) Cities"--if you click through the images will come up--plus Alex B.'s comment in yesterday's blog entry about the Cubs/Sox and his point that the US Cellular Field could have been designed to capture the beauty of the Chicago Skyline as the defining architectural element of the in-stadium experience).

Note that over the life of the Verizon Center, most of the retail locations not on 7th St. (the best place to locate) have failed.

- Philip Bess, City Baseball Magic--Plain Talk and Uncommon Sense about Cities and Baseball Parks

Photo by Mike Kepika of the San Francisco Chronicle. People leaving the streetcars to see a Giants game at PacBell Park.

3. That includes locating the facility so that transit accessibility is primary and convenient, to limit motor vehicle trips to the facility.

4. Related, that includes putting an agreement in place with regard to funding transit service (if necessary), before the team starts playing ("Incentives vs. requirements: stadiums/arenas and transportation demand management"), but also to develop package deals and incentive programs to promote transit use.

5. Mitigating the negative impacts for those businesses that are displaced in the construction of the new facility, and going the extra distance to retain them (e.g., the Nationals stadium caused the Washington Glass School art program to move to Maryland, because not enough effort was made to assist them in staying).

6. Making agreements on when events are scheduled, because the team owners will try to schedule the events in a manner that makes it difficult for people to patronize non-arena establishments, especially before the game. Instead, people go directly to the venue, and spend all their money inside, limiting spillover benefits.

7. Having a ticket tax, such as that suggested by the Hill District Consensus Group in Pittsburgh (Hill District seeks more arena-area parking money for development" and "SEA urged to use a portion of parking revenue to support Hill" from the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette) to fund economic development in the area. Other fees on the ticket can fund arena improvements sure, but there should be an ongoing funding stream to mitigate negative impacts on the neighborhood that result from events.

Economic issues

1. Localities funding stadiums should have an ownership interest/financial interest in the revenue stream from the team and stadium.

While many agreements give the locality ownership of the facility around the time the facility is no longer worth anything, communities don't make much money on the facility during the successful period.

DC paid more the Nationals Stadium than the owners paid to Major League Baseball to acquire the team, but the city gets much less back economically than the owners.

Note that this is a nonstarter with the professional sports leagues. And Congress will never step up and pass legislation that gives more power to localities vis-a-vis sports teams and the leagues. For example, Major League Baseball is legally allowed to collude.

2. Leagues should not fight local taxation on player earnings. DC is in a special place because it can't enact a "commuter" tax. Many other states take the position that income is earned by game, where the game is played, and tax player salaries accordingly. DC can't do that, and Major League Baseball lobbied to ensure that this wouldn't change. Anyway, localities where stadiums-arenas are located need to be able to tax player salaries in part recompense for the expense of siting and maintaining these facilities.

3. Metropolitan areas should create multi-jurisdictional financing authorities (Maryland does this at the state level) to fund such facilities, rather than putting all the burden on the center city, comparable to how the Allegheny County Regional Asset District and other special funding districts work.

-- Maryland Stadium Authority

These agreements and systems need to be in place long before sports teams and leagues come calling.

The non-city jurisdictions won't like it, but the fact is that these facilities need to be located in central places, and the burden for funding them needs to be more fairly distributed than it tends to be right now. Also see "Firm plan for new stadium still eludes Richmond area" from the Richmond Times-Dispatch.

-- Richmond Metropolitan Authority

-----------

I am sure there are more points to be added. This is a start.

Labels: public finance and spending, quality of life advocacy, sports and economic development, stadiums/arenas, urban design/placemaking

3 Comments:

This is a nice blog.

Visit here-pharmacy online.

Great post! Great insights on urban commuting! Shuttle Mumbai by MYLO Rides truly simplifies daily travel with reliable schedules, comfortable rides, and seamless booking for professionals. Visit us for more!

Shuttle Mumbai

Great post! Using the MYLO Rides BUS APP ensures efficient routes, safe rides, and a better commuting experience for employees every day. Visit us for more!

BUS APP

Post a Comment

<< Home