DC and parking, parking, parking

I laughed three Sundays ago, when I saw an op-ed ("D.C.'s .’s plan to make it even harder to park") in the Post about the horrors of DC reducing requirements for the provision of parking in new buildings in the city, in what the Office of Planning defines as high quality transit service zones (subway stations, high frequency bus service).

I laughed because the piece was co-authored by Sue Hemberger, someone that OP was trying to massage through her participation in the "Citizen Planner Initiative" over the summer and Mahlon Anderson of the Mid-Atlantic chapter of the American Automobile Association. Clearly, OP's machinations had no effect.

Citizen planners + the AAA is a bad combo to my way of thinking.

The "government" countered last Sunday with an op-ed ("Parking rules for a 21st-century D.C.") by Harriet Tregoning and Terry Bellamy, respectively the directors of DC's Office of Planning and Department of Transportation.

The debate continues.

Lord Grantham's relevance to DC's zoning update

The hullaballoo about changes to parking regulations in the city, ranging from discussion in blogs, including this one, newspaper articles, community meetings, and a recent "op-ed" in DC Watch about how the city is anti-suburban and how this is counter to the symbiotic positive relationship between cities and suburbs by Gary Imhoff (note that this alleged positive symbiotic relationship is not an element of academic scholarship on the topic), made me think about Lord Grantham and Downton Abbey and the relevance to planning for the future of cities and DC specifically of that show's story line about responding to societal changes.

Robert Crawley's failure to adequately plan for the economic future of Downton Abbey first, by not diversifying his investments but instead putting most of his (via his American wife) money into the Grand Trunk Railroad in Canada which went bankrupt so he lost virtually everything, and his opposition to modernizing the farming operations of the estate, preferring instead to direct the windfall received via Matthew into "investments" with Charles Ponzi, put everything at risk.

They would have lost the estate--the fate of some of their other relatives up in Scotland--had Crawley not eventually acquiesced to Matthew's plans for modernization.

The 20th Century required new ways of conducting business and managing the estate, just as cities keep needing to adapt as the way people live, work, and get around changes as the centuries change.

Although the reality is that the best ways for getting around the city haven't really changed over the last 100 years, from the standpoint of modes.

Strong cities are built around urbanism and transit, not automobility

Cities are good at being some things and not others, and it is important to recognize and focus on your advantages, rather than making the city over for something it is not suited.

That is the case with the walking-biking-transit city versus the spatial patterns that support automobilty. (Image from The House Book by Keith DuQuette.)

That is the case with the walking-biking-transit city versus the spatial patterns that support automobilty. (Image from The House Book by Keith DuQuette.)Which I write about all too frequently, but apparently this reality still escapes many.

The city was designed to optimize walking first, and then biking and transit.

See Adams, J.S. “Residential structure of Midwestern cities.” Annals of the Association of American Geographers, 60: 1, pp. 37-62 (1970). Melosi, M.V. “ The Automobile Shapes the City: From ‘Walking Cities’ to ‘Automobile Cities.’ and Muller, P.O. “Transportation and urban form: Stages in the spatial evolution of the American metropolis,” in Susan Hanson and Genevieve Giuliano, eds., The Geography of Urban Transportation (New York: Guilford Press, 3rd rev. ed., 2004), pp. 59-85.

Fortunately today, trends for living and commerce favor (some) cities once again--those on the coasts, those with transit systems, those with walkable urban places, those not focused so much on automobility--so they are gaining population, and these new residents are bringing vital investment to places that had for so long experienced only disinvestment.

The thing is, do you plan for the future, or do you continually aim to adopt planning practices, particularly those focused on automobility, that ultimately are inappropriate for ensuring success of the city? Do we invest in car-based mobility--the equivalent of a risky, dangerous, speculative investment--or do we invest in sustainable modes--walking, biking, and transit--complemented by car sharing, electric vehicles, and significant investments in transit expansion?

Seattle as a better example of how to change parking policies

Seattle as a better example of how to change parking policiesIn 2007, at the Main Street national conference in Seattle, I saw an amazing presentation by the City of Seattle Planning Department on their "neighborhood business district" program, which included significant zoning changes, including an element of Seattle's longstanding policy to reduce automobility centrality in their planning and development practices.

In the mid-1980s, Seattle removed minimum requirements for parking provision in new construction Downtown. THe city did not die, in fact (of course, assisted first by Microsoft and then by Amazon) the city, especially investment Downtown, improved.

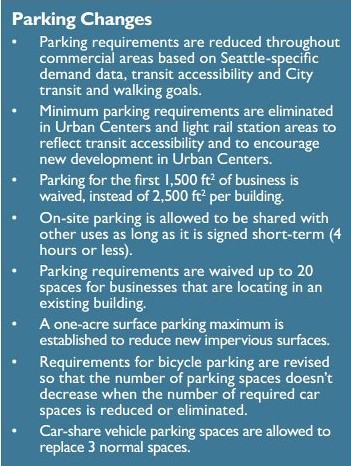

Around 2006, in advance of the launch of light rail service, and as part of a wide ranging comprehensive set of changes focused on improving neighborhood business districts they extended this policy to the next level of urban centers (neighborhood business districts such as University Village by the University of Washington) and commercial districts to be served by transit stations (such as Beacon Hill), not unlike what DC proposes to do in the context of the Zoning Update.

In fact, I was so impressed with this presentation that I immediately sent email to various people at DCOP and wrote a blog entry about it ("The City of Seattle has the most amazing planning for neighborhood business districts").

Seattle as an example of how to justify changes to parking regulations: a data-based approach

Seattle as an example of how to justify changes to parking regulations: a data-based approachThe thing is, knowing that such policies are likely to be met with a great deal of opposition, just like what has been happening in DC with regard to the zoning update and the Chicken Little responses, I have been disappointed at the failure to plan for opposition by having voluminous data to support the position for change.

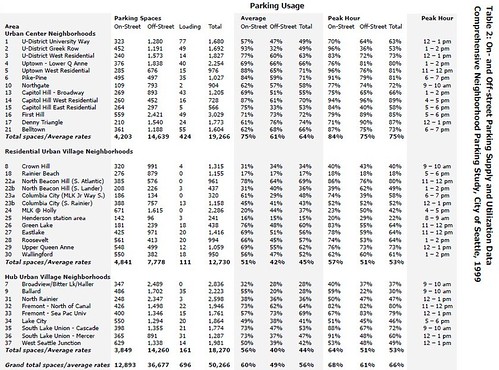

To wit, data on parking usage and availability throughout the city. Seattle conducted parking studies for the entire city in 2000 and 2004, and had solid data on the experience Downtown, and this data shaped the changes, provided support for the changes, and provided real data rather than supposition about changes. (I have not seen DC produce comparable data on parking practice at the neighborhood and district level in the manner in which it has been done in Seattle.)

Part of the problem in DC is that we are really two cities, the urban city at the core, and the more suburbanized outer city--much of this part of the city was developed after 1920, during what Muller calls the "Recreational Auto Era," where both broader urban spatial patterns and housing design began to adapt to the automobile.

In the outer city, more residents own and rely upon cars to get around, even if they are near to transit, the neighborhoods tend to be less dense, making walkability less efficient in many areas, although there are many neighborhoods outside of the core that are dense enough and well served by transit, so that automobility isn't in fact required.

But that's not what they think.

King County as an example of how to develop and market new practice: developing parking-specific tools to support reductions in parking requirements

The Puget Sound Business Journal reports, in "How many parking stalls does an apartment complex need? New tool gives some answers," about a new tool, the King County Multi-Residential Parking Calculator, for determining the right amount of parking at multiunit housing developments.

The project, called Right Size Parking looked at parking use at more than 200 different developments across the county in developing the tool and the recommendations. From the article:

The long-held belief is that almost every household owns at least one vehicle. But the reality is that a combination of factors — location, price of parking, proximity of housing to jobs and access to good bus service — are the true drivers of parking demand.

Metro officials said that while one household may need two cars, a growing number of households living in denser urban areas are choosing to go carless.

The findings of the study show that on average, multi-family residential developments offer 1.4 parking spaces per unit — yet only one space is actually being used.

The research also concluded that the right number of spaces per unit varies among locations, which suggests parking requirements that work in Seattle are different than those in Bellevue, Kirkland or other cities.

This extends the work done in Seattle previously, and is the kind of data-based approach that we seem to be lacking in DC, as it relates to justifying the proper course of future action, by strengthening the city's focus on sustainable mobility rather than automobility.

Note too that in 2005, WMATA did a study, the Development-Related Ridership Survey, to determine the utilization of transit versus other modes in different types of development. The WMATA study found that proximity to transit stations--the closer the better--shaped how much residents and workers. And in-city locations demonstrated greater transit ridership compared to denser suburban and outlying suburban stations.

Data and education is necessary to quell opposition to pro-urban, pro-city zoning changes

Otherwise we are going to continue to experience the ongoing battle between the suburban and urban city, the young and old, and the innovative versus the mossbacks--pick your issue grouping and argue accordingly--and we will continue to suffer the consequences.

Similarly, for years I have argued that the Office of Planning, rather than move immediately into a zoning update phase after the Comprehensive Plan was approved in 2006 should have instead then spent the next 2+ years educating people about the plan and the city's future.

The way I read the Comp Plan, it supports sustainable mobility and de-emphasizes the kind of suburban development and spatial practices that were enshrined in the 1956 Zoning Code, the code which still guides current planning and development practice in the city.

Apparently many people disagree with my interpretation because they are arguing that the Comp Plan language does not support focusing on transit and other forms of sustainable mobility, does not support accessory dwelling units, and incorporating mixed use developments in commercial districts, etc.

The lack of consensus we have on what the city is and should be is the outcome of the failure to use the Comp Plan and the process as a tool for education and building a common vision.

I am not too hopeful about the Zoning Update process as it relates to parking, accessory dwelling units, and other elements, regardless of the "soaring language" present in the Comp Plan.

It's clear that there is a major disconnect between cherishing the past and focusing on maintaining the status quo, rather than preparing the city as a place to live, work, and play in the 21st Century.

New section of links on the webpage

Note that the King County Metro Transit Right Size Parking study and calculator and the very good blog Reinventing Parking (check out its various resources on the issue including an awesome bibliography) have led me to create a subsection of links on parking within the various long list of "Dr. Transit" related links in the right sidebar.

I hope to be adding to this section over time.

Labels: car culture and automobility, parking and curbside management, sustainable transportation, transportation planning, urban design/placemaking, urban revitalization

10 Comments:

The only disconnect is with a relatively small, but vocal group of Ward 3 and Ward 4 residents whose entire existence is centered around automobility.

OP and urban advocates should move forward with the city and region in the ways that are crystal clear.

The problem is not only are they vocal, they are connected. And many of the city's councilmembers aren't fervently committed to urbanism.

And I don't think OP is doing a good job countering.

Frankly, when I was writing this piece yesterday I was thinking about the preservation "debate" and how it has been mishandled so often in DC over the past 10+ years, and how preservation advocates haven't learned from their defeats, and upped their game.

I worry that the zoning update is showing a similar pattern.

I am not part of the ProDC effort, maybe it will make a difference.

i'd love to know what more you believe OP could do to placate this group. Why even bother having these people on the committees?

My take is that it is a waste of time to engage them because no matter the soundness of the logic or argument, the bottom line will be that they oppose any new development. I believe it is more about preventing building than preserving the car and that the smarter ones use the "war on cars" to enlist those who really don't car one way or the other.

The problem is OP wants to do away with parking minimums at the same time DDOT is saying residents in new buildings in commercial zones can now get RPP. The combination is a one-sided windfall for developers whose tenants can now park on surrounding RPP streets. Arlington waives parking requirements for buildings that give up RPP.

The costs of cars should be internalized in a new project- either by the developer handling them or possibly giving up some demand in order to not have any parking available in house or on street.

As with many "progressive" ideas DC gets this half-right which still is wrong.

While as always I appreciate Richard's efforts, I think his advocacy is misplaced here.

Big picture: parking minimums don't mean you can't build building w/o parking. It means developers have to jump through a few hoops. Regulations is about drawing the line, and I'd rather give city planners an additional tool in bargaining.

I'm cognizant that there is overwhelming presssure in American public life to bow down to the automobile. I admire resistors. However, sometimes even the resistors are wrong.

As I've said before, it is car-lite, not car-free that we are moving towards.

there are a lot of fathers in this parking minimus debate, but lets get back to an earlier idea -- actually cities benefit by staggering development and not creating a monoculture. right now I'm sure there are developer who would love to plaster DC with 6 story cheap buildings with no underground parking. There is demand, right now, for that, and you can get the financing.

In 10 years? In 25? In 50? That is how we create slums and pockets.

So constricting growth a bit -- and causing property values to go up for everyone -- isn't such a lose.

Why do we having residental parking problems -- simple. We are converting houses into condos, doubling the density, and asking the rich new residents to park in the street. It isn't the mythical maids coming down to park all day -- it is your fellow residents.

I love the comparison of the pro-parking minimums, pro- drive everywhere for everything crowd with Lord Grantham. It's perfect! They are both so caught up in the past that they fail to recognize much less adapt to the changes happening around them.

Investing in parking and other automobile-centric infrastructure in a walkable city with good transit in 2013 is exactly like investing in a redundant transcontinental railroad in Canada during WWI. Frustratingly, if gas costs $8-$10/gallon a decade from now, which it very well could, I can see many of the car crowd screaming bloody murder about how the city failed to invest in transit, especially in their neighborhoods. (I'm sure many of them also wring their hands about childhood asthma rates in our city. They just cannot understand why they are so high and why somebody doesn't do something about it...)

On a side note: interestingly, the Grand Trunk Pacific was absorbed by the Canadian National Railroad and the route is still open today, including a passenger train. But the dreams of Prince Rupert growing into a port and city to rival Vancouver remain just that -- dreams. It's population is 12,000...

1. well, the interesting thing about Grand Trunk, while it was duplicative, is that just like the presumptive Crawley heir, the Chairman died on the Titanic. I wonder if that contributed to the firm's demise.

2. rg, wrt your point about transit and reach into various neighborhoods, it's very interesting in how the book _Between Justice and Beauty_ recounts how various DC neighborhoods clamored for streetcar service, back in the late 1800s.

3. Charlie, you're right that there is a difference btwn. no parking and some parking, and some parking vs. lots of parking, and induced parking and driving.

And to be fair to the antis, there is a difference wrt transit access and proximity in Columbia Heights vs. Friendship Heights, and how this shapes car usage.

But at least I am willing to look at the issue in a nuanced fashion, and the antis, mostly, are not.

I mean, some woman criticized my mobility scenario as something for younger people only, when it is something I do, and it turns out I am a year or two older than she is...

Although speaking of "current conditions" I have to admit thinking about biking up hill back to FH after a day's work might be a bit daunting.

4. I came up with the Lord Grantham thought first wrt Gary Imhoff, and his paean to suburban-city integration and love.

Charlie,

Of course, DC's zoning revision is not getting rid of parking minimums at all - but rather adjusting the levels of what those minimum requirements should be. And, in some parts of the city, the minimum requirement ought to be zero.

If anything, those kinds of regulations should always err on the side of under-mandating, given the cost of providing the resource. Allow the market to work a bit, give it some flexibility in meeting the requirements - or else be prepared for suffering the ills of unintended consequences.

The point about parking-free developments becoming slums is bullshit.

As for the case about restricting growth a bit - that's fine. You can make that argument. However, we aren't constricting growth just a bit, we're constricting it a lot. And we're paying a price for that.

@AlexB: "We?" The city? the regulations? Or the ongoing problems with financing multi-unit condos? Or the commercial real estate market?

All of it, as all of those parts are inter-related.

Post a Comment

<< Home