An arena subsidy project I'd probably favor: Sacramento

Spending on sports is a substitute for other forms of entertainment, not additive. Most of the research on the economic impact of professional sports is pretty clear that the actual spending merely substitutes for other spending on entertainment. This means if you don't have a sports team event to go watch, you spend roughly the same amount of money on movies or concerts or plays and other media, so that at the scale of a metropolitan area, the spending is about the same with or without a sports team.

DC United soccer team rendering of proposed stadium at Buzzard Point.

BUT there are some subtle issues involved when making decisions about public subsidy for sports facilities. This is relevant to most every city being asked for money.

For example, in DC now there is a deal brewing to provide support for a new soccer stadium (see "Here are 8 ways DC can get the most out of a new soccer stadium" via GGW for an argument about why the deal being developed doesn't make sense) and even more insane crazy machinations by City Councilmembers for a study about building a super-duper football stadium and entertainment complex to bring the Washington Redskins football team back to the city ("Jack Evans: RFK site ideal for Redskins stadium," Post, "The 5 Strangest Parts of Vincent Orange's RFK Stadium Plan," Washington City Paper).

Next City has an article about this problem more generally, riffing off a $450 million deal for the Detroit Red Wings hockey team

But there is no question that certain types of facilities have better results than others.

It may be worth considering providing public subsidies if the stadiums/arenas are key elements in helping to reshape communities in ways in which transportation and land use projects are intertwined and supports simultaneously the creation of mixed use districts and the attraction of new residents and new commercial activity to the center city versus the suburbs.

If it does that then it is worth considering. If it doesn't, it's not.

The difference in opinion concerns how much is it worth spending to do so and whether or not to do it, especially given the zero sum game of available funds at the local level and the loss of ability to fund other projects, and the reality that most of the benefits confer to upper income segments.

Some people argue yes, always, give sports teams the money, while others argue no, almost always.

What are the characteristics of sports facility subsidy projects that may be revenue positive for a community? Where I think we need to focus is on identifying the characteristics--positively or negatively--that shape the success of sports facilities in terms of community economically supportive impact, rather than merely reflexively oppose or support public subsidy of such facilities categorically.

Support what makes sense economically. Oppose what doesn't make sense. Have arguments for why particular ways for siting and building facilities matters.

It's hard to measure accurately ancillary real estate development spurred by the presence of a sports facility. The reason I have argued pretty vociferously about the broader economic impact of baseball and basketball-hockey facilities in DC is because much of the adjacent development proximate to those buildings would have happened anyway, and so it is misleading to argue that the sports team gets all the credit.

BUT, I have come around on the idea that sports teams based in cities attract suburban visitation, and depending on whether or not other things are going well for the city, they can be a kind of recruitment and marketing effort that makes a difference in city branding and positioning in the context of the metropolitan economy.

And when much of the traffic generated by such a facility going to and from games is captured by transit, this minimizes significantly potential negative effects also, increasingly the value. In-city locations are likely to have better transit connections than suburban locations.

Teams located in cities can help cities rebalance spending vis-a-vis the suburbs--even if at the metropolitan scale spending stays the same. Depending on the nature of the taxation regime, spending at a stadium-arena absorbs spending from somewhere else. A facility in the city generates revenues that might have otherwise been spent in the suburbs. This kind of effect isn't picked up when looking at data at the metropolitan scale.

Depending on urban design and other considerations, center city arenas and stadiums can anchor new real estate and retail activity. In a metropolitan area, when teams are often based in center cities, and center cities typically have lost out to the suburbs overall in terms of commerce and residential, center city-based teams can attract new economic activity to the city, as part of the reproduction of the city as an entertainment and tourism center and less focused on production.

Characteristics that support successful ancillary development associated with professional sports facilities:

- isolation or connection: how well is the facility integrated into the urban fabric beyond the stadium site and does it leverage, build upon, and extend the location and the community around it;

- size of the facility (baseball, football, basketball, hockey, soccer), bigger stadiums--football stadiums specifically--are harder to integrate in the urban fabric;

- frequency of events held by the primary tenant--baseball has 82 home games/year, football about 10 including pre-season, basketball and hockey have 41, soccer about 17--so football stadiums are very rarely used (according to the Chicago Sun-Times article "Emanuel mulling 5,000-seat expansion to Soldier Field," the facility holds about 22 events including annually, 12 non-football events);

- how many teams use the facility, maximizing use and utility of the building--for example, Verizon Center in DC is used by professional men's and women's basketball, hockey, and one college basketball team for more than 100 sports events each year;

- are events scheduled in a manner that facilitates attendee patronage of off-site businesses--a business isn't an anchor if it aims to not share its customers; the earlier events are scheduled, the harder it is to patronize retailers and restaurants located off-site, at night during the week, there is limited post-game spending as well, on the weekends it's a different story with more opportunity to patronize off-site establishments--teams manipulate scheduling to reduce spending outside of their on-site and 100% controlled facilities;

- use of the facility for non-game events drawing additional patrons--such as concerts and other types of programming; and

- how people travel to events: automobiles vs. transit--if automobiles are the primary way people get to events, then large amounts of parking usually in surface lots needs to be provided, making it difficult to foster ancillary development because of lack of land and poor quality of the visual environment, whereas if transit is the primary mode, then more land around a facility can be developed in ways that leverage the proximity of the arena.

In DC, the old RFK Stadium, surrounded by parking lots, never was an economic powerhouse, while the Verizon Center is integrated into downtown and sits on top of three subway lines.

Similarly, in Chicago, New Comiskey Park was specifically designed to disconnect from the surrounding neighborhood and to eliminate businesses that competed with the stadium for attendee expenditures on food, drink and momentos, while Wrigley Field is integrated into its commercial area and the differentiated impact from these choices is glaringly obvious as the neighborhood by Comiskey Park remains forlorn, while Wrigleyville-Lincoln Park is successful.

The Meadowlands football stadium is isolated with limited spillover economic benefit, while Madison Square Garden is in the heart of the city and event attendees are shared with businesses around the arena ('Local Businesses Pay for NHL Lockout," Fox Business).

Transit usage is key. One way to minimize negative traffic effects is to locate stadiums-arenas proximate to high capacity transit, subway and railroads preferably.

Patrons can be induced to use transit, by reducing available parking and charging high prices for it. This reduces two of the biggest negative effects of sports arenas and stadiums-- automobile traffic and the obscene amounts of land dedicated to parking. Both make it hard to spur adjacent development.

For DC proper, when baseball, hockey and basketball games occur, there can be congestion on transit--especially for baseball, which is only served by one subway line, while the Verizon Center has all five lines within 4 blocks, including 3 right at the arena--but not so much on the roads.

But because the professional football team's stadium isn't well-located on the transit system, when there are football games, especially night games that intersect with rush hour, there is terrible road congestion on freeways and arterials.

Note the freeways and parking lots around Atlanta's football and baseball stadiums.

But it's not merely having transit availability, transit has to already have a presence and a willingness to be used, and have high capacity, in order for transit connections to make a difference in terms of mitigating negative impacts from such facilities.

Difficulties finding data on transit use associated with sports event attendance. I've had a difficult time finding good data on transit ridership associated with facilities proximate to high speed transit with two exceptions.

The Chicago Cubs commissioned a study, Wrigley Field Game Day Traffic and Parking Management Plan, which found that 40% of event-goers rode the Elevated, but minimal bus use.

Another example is how the Long Island Railroad has experienced ridership gains of 400% or more, for events held at Barclays Arena in Brooklyn ("LIRR: Ridership boost from Barclays events," Newsday). Transit officials argue that subway ridership has increased also, but haven't provided figures, because it is hard to track significant spikes in subway ridership, which is already high. From the article:

LIRR ridership has surged an average of 334 percent on event nights at Barclays, pushing the transit system's 2012 ridership numbers slightly ahead of the previous year's, according to railroad officials.While it would seem like data would be more widely available for Madison Square Garden in Manhattan, because the location is so well-connected to subways and suburban railroad service, and because of high usage anyway, it's difficult to sort out spikes associated with sports events and MSG doesn't have data on how attendees get to the facility.

Similarly, I haven't been able to track down data on DC's Verizon Center and transit use, from either the owner of the facility or WMATA.

Bus or limited light rail connections aren't as good as high-capacity transit options--in recent years, transit systems in Seattle, Dallas, and New Jersey ("'Mass-Transit Super Bowl' Hits Some Rough Patches in Moving Fans," New York Times) have failed miserably in providing service to special sporting events that exceeded the capability of their systems to absorb extra-normal crowds. (Although this isn't a problem unique to the US. See "World Cup: Transport system lets down fans" from the New Zealand Herald.)

-- Transportation Planning for Planned Special Events, Federal Highway Administration

The new North Shore Connector in Pittsburgh provides light rail connections to the city's baseball and football stadiums.

Special marketing promotions involving transit use. Some transit authorities or teams promote transit use for patrons. In DC, the Verizon Center has a contract with WMATA to pay for service for patrons if games end after normal operating hours for Metrorail. Unfortunately, the Washington Nationals baseball team refuses to sign a similar kind of contract. (Such participation should have been required as part of the lease agreement for the stadium, which was built and is owned by the city.)

In Pittsburgh, a light rail extension to serve Northside and its stadiums and a casino provides free transit service, paid for in part by the Pittsburgh Steelers football team and the Pittsburgh Stadium Authority. See "Trips on North Shore T will be free" from the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette.

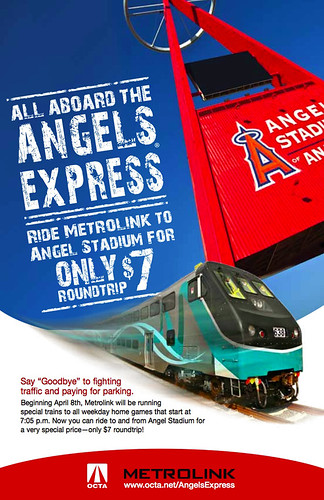

And Metrolink, the Southern California passenger railroad system, has a variety of programs focused on promoting use of their service to get to professional sports events. See "Incentives vs. requirements: stadiums/arenas and transportation demand management."

And Metrolink, the Southern California passenger railroad system, has a variety of programs focused on promoting use of their service to get to professional sports events. See "Incentives vs. requirements: stadiums/arenas and transportation demand management."The need to improve transit wayfinding for game-day riders. Since many event-goers are unfamiliar with transit, to fully leverage transit usage and to limit station congestion and other problems, improvements in wayfinding are often necessary. See "How to improve CTA traffic flow to Wrigley Field for Cubs games" from Chicago Now as an example.

Suburban benefit from stadium-arena presence seems negligible. For some reason, it doesn't appear as if locating arenas and stadiums in suburbs has the same positive effect on ancillary economic development.

This is definitely the case in the Detroit area for the suburban basketball arena and the since demolished Pontiac Silverdome, once home to the Detroit Lions football team.

I would argue this is the case in the DC suburbs, where neither the now demolished Cap Centre nor the extant FedEx football stadium have provided much additional economic development to the areas around those facilities.

The same goes for the Meadowlands football stadium in New Jersey, the hockey arena for the New York Islanders in Nassau County, etc.

Left: Sacramento Bee graphic on proposed siting of a new basketball arena in Downtown Sacramento.

A new arena for the Sacramento Kings: can it reposition their Downtown? Even though some residents are calling for a referendum on whether or not to subsidize a new arena that is being proposed for the Sacramento Kings basketball team, which narrowly missed being moved to Seattle ("No ruling yet in STOP arena lawsuit," Sacramento Bee), the reason that I think it could be worth it for the City of Sacramento to spend heavily on a new arena for the Sacramento Kings basketball team is that it will help to recenter economic development on the city away from the suburbs, when much of the commercial and residential activity has already moved to the suburbs ("Kings’ arena is the only real plan to revitalize downtown Sacramento," Bee).

-- Arena coverage webpage, Sacramento Bee

It took me a long time to concede a similar process with regard to the Verizon Center's impact on Downtown Washington, partly because as developed in the western and center parts of Downtown maxed out a movement east was preordained, but even so there is no question that the building and its activity has contributed positively (it helps that Georgetown U plays its basketball games there too, which is an added benefit) by making a part of Downtown particularly active and populated in the evening and weekend hours, when much of Downtown--especially those districts that are primarily office--are seemingly empty and somewhat forlorn.

When the basketball and hockey teams moved to the city from Suburban Maryland it was a bold step because at the time Washington, DC had real problems economically (the city was in bankruptcy), politically, and in terms of public safety.

Sacramento needs that kind of economic jumpstart.

The SF Giants baseball stadium is well integrated into the urban fabric and many event-goers get there by transit. Photo by Mike Kepika of the San Francisco Chronicle.

Repositioning the value of transit in Sacramento. As importantly, by locating the arena to take advantage of the metropolitan area's light rail system (38.6-miles of track, three lines, and 48 stations) which isn't heavily used now (just under 50,000 riders daily), the metropolitan transit system could get a significant boost in sampling--use during games--and increases in ridership at other times, because of the better linking of high-demand destinations to the existing system footprint.

Interestingly, the transit authority has suggested that a mandatory 50 cent surcharge be added to tickets, to contribute to increased transit service and public safety. And in return they would provide free transit to ticket holders, which they estimate would be used by 10% to 20% of patrons. That's not that high compared to the well connected stadiums and arenas in San Francisco, DC, New York City, Chicago, Boston, or Philadelphia maybe, but it is a start.

-- "Light-rail officials: Trains could be key route to downtown arena," Bee

-- "Kings expected to pay $500,000 to support streetcar line," Bee

Note that UTA in Utah treats a University of Utah sports event ticket as a game day all-day transit pass ("Use Your University of Utah Game Day Ticket as Transit Fare") and in Blacksburg, Virginia the transit system charges a $5 flat rate fare for buses on Virginia Tech football game days for three hours before the game and one hour into the game, but after that, transit is free until 90 minutes after the game.

Conclusion. Rather than being reflexively for or against public subsidy of sports teams and their facilities, it's important to dispassionately analyze why certain facilities are successful at sparking additional development while most are not.

Factors include whether or not the facility is connected or isolated from the community outside the facility, its size, how many events are held there, whether or not people are discouraged from spending time and money off-premise, and whether people drive or use transit to get there.

As an example, reshaping and repositioning Downtown Sacramento as a place to visit, shop, and live is valuable economically. Is a publicly subsidized arena better integrated into the Downtown fabric the right way to spur revitalization energy and attention on Sacramento, both in the core and elsewhere? Maybe the arena + the related proposals for retail and other development is the way to bring about revitalization after more than 30 years of fits and starts, even though it comes at a significant cost.

These are tough questions to answer, but it is easier to do so when an independent and robust evaluative framework is used, rather than relying on the attestations of teams and public officials who are enamored with them. The following characteristics are the start of such a framework:

- isolation or connection of the facility to the urban fabric beyond the stadium site;

- size of the facility and its ability to be integrated into the urban fabric;

- frequency of events held by the primary tenant;

- the number of teams using the facility, maximizing use and utility of the building;

- whether or not events are scheduled in a manner that facilitates attendee patronage of off-site businesses;

- use of the facility for non-game events drawing additional patrons;

- how people travel to events: automobiles vs. transit.

Labels: action planning, capital improvements planning, civic assets, public finance and spending, sports and economic development, stadiums/arenas, tax incentives, tax increment financing districts

4 Comments:

Absolutely -- although I could shortern your post to "No footbal stadiums."

A few other points:

1. Fan experience. Look a lot of the places that fans love (Wrigley, Fenway, Baltimore, etc) as sports sites are regions, not just a stadium. The key is capturing some of that extra revenue and throwing it back. Align incentives.

2. Walking vs. transit. Look, transit is all good, but you have to be careful. What happened in cleveland (destorying the FLATs to build a stupid light rail to the staidum) is transit for the sake of transit. Ultimately it is the ability to walk.

3. If city planers don't get retail, I think they get the event booking business even less.

your first sentence made me laugh, thanks!, although it isn't that simple.

You're right about the walking being even better.

And plenty of arenas-baseball stadiums are poorly situated or set up to be deliberately isolated so it isn't just size per se but urban design and form.

2. I'm all ears for more expounding on your point #1. In some ways that goes against the desire and trend of the team to capture as much as 100% of total spend by the attendees. (... e.g., the post on sports team facilities as revenue platforms).

That makes it hard to align incentives to encourage the team to allow spending at other facilities.

In preparing this piece, I e-talked with the Newark Star-Ledger journalist who wrote the piece I cited about MSG and we talked about isolated facilities. He used that word specifically ("isolated") and I thought that was a better sum up of the issue and I incorporated that work.

I asked him about the Nets in Newark and we didn't come to a common understanding in terms of +/- effect and why the team left.

Now I am thinking that there were not enough fans in NJ and a reasonable amount of pain-in-the-assedness to get to Newark from the places where the fans live, reducing the potential for positive impact.

the counter-example of LA:

https://www.bisnow.com/los-angeles/news/commercial-real-estate/when-it-comes-to-professional-stadiums-los-angeles-prefers-its-owners-to-pay-for-them-87476

4/19/2018

The negatives of a new soccer stadium for West Ham, London. Was the Olympic Stadium. The problem is the stadium wasn't designed in advance for soccer too, and the game day experience isn't so great for fans:

https://www.lrb.co.uk/v40/n08/helen-thompson/short-cuts

4/19/2018

2. Plus I've written about the Miami Marlins. They got a new stadium but the team didn't invest in better team, and attendance didn't grow, year by year record among the worst in baseball.

Post a Comment

<< Home