Even more about bicyclists, bicycling as a challenge to motor vehicle primacy

(This piece is in response to a letter to the editor in yesterday's Washington Post.)

Last week, in the discussion about the barrage of articles in the Washington Post about cycling, cyclists as terrorists, as riders on sidewalks, and non-demons, I made ("Urban-suburban divide and cycling") a number of points. The main ones are:

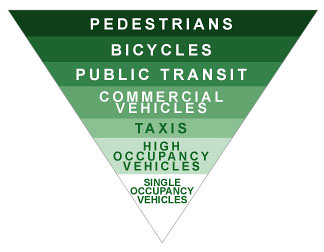

Sustainable transportation hierarchy. Image source: Transportation Alternatives. (This is sometimes called the Green Transportation Hierarchy.)

Sustainable transportation hierarchy. Image source: Transportation Alternatives. (This is sometimes called the Green Transportation Hierarchy.)1. For efficiency and to best promote exchange*, urban transportation policy should prioritize sustainable modes, that is walking, biking, and transit.

This is in contrast to suburban transportation policy, which prioritizes motor vehicle movement, and has dominated US transportation since the 1940s,

2. Promotion of cycling as a preferred mode should prioritize the ability of cyclists to accomplish trips of up to 5 miles as efficiently and quickly as possible to be competitive with motor vehicle trips.

For reasons of physics and the transfer of energy ("Why bicyclists hate stop signs," Access Magazine), it is disadvantageous for cyclists to stop at every stop sign and red light, which otherwise cripples the ability of a cyclist to "compete" time-wise with a car trip over "short distances."

3. Traffic laws prioritize motor vehicle movement in virtually all situations, with one exception.

The exception is most commonly referred to as the "Idaho Stop," because this type of bicycle traffic movement--that when there is no oncoming traffic or significant breaks in traffic, cyclists should be able to run through stop signs and traffic signals--is legal in the State of Idaho.

4. In my opinion (but frankly, most of the time by the time I write something here or elsewhere, it's pretty clear that I'm right) most opposition to bicycling and cyclists as expressed by motor vehicle operators is not a reaction to cyclist behavior but to their perception that cyclists are usurping the priority and privilege of motor vehicle movement within the perceived "hierarchy" of transportation modes and the "rightful place" of motor vehicles at the top of the hierarchy.

5. But opposition to cycling is mostly couched in terms referring to the "reckless behavior" of cyclists running stop signs and red lights.

While there is no question that some cyclists do engage in reckless action--running stop signs and red lights when there is oncoming traffic and riding on sidewalks at speeds that can endanger pedestrians--reckless action is a different question than "following the law," something advocated in a Sunday Washington Post column by Petula Dvorak ("Hey, infuriated D.C. bikers and drivers, can’t we all just get along?") and by Linda O'Brien in a letter in yesterday's Post.

Linda O'Brien makes me realize that "I am living in my own private Idaho" and I am fine with it. She writes:

The July 11 Style article “In D.C.’s bike wars, here come the spokespeople,” peddling civility by and toward bikers downtown, revealed the reason cyclists should be aggressively ticketed by D.C. police when they break the rules: in the one brief capsule of time described in the article, five cyclists sped through a red light. An ambulance, fire engine or police car could have been speeding into the intersection, and the cyclists would have caused a tragedy, among many possibilities. If rude and rule-breaking cyclists start receiving fines for their behavior, maybe they would reconsider their importance over the importance of every other individual on the streets. If that doesn’t work, the bike lanes need to be considered a failed experiment.Her letter makes a bunch of under-founded statements and jumps to a conclusion which is illogical. She comments that cyclists ran a red light, that it could have been catastrophic if there had been emergency vehicles coming--but there weren't and the article doesn't discuss if there was any oncoming traffic, and then she makes the claim that bike lanes are likely a failed experiment, based on a set of information that has nothing to do with the efficacy of bike lanes.

Not to mention she re-llustrates the point I made in the earlier piece, that most of the time, suburban residents don't have standing (the right combination of knowledge and experience) for making recommendations on how center cities should manage transportation policy.

The traffic laws written for motor vehicle traffic don't work in terms of optimizing sustainable mobility in urban settings and should be changed.

So long as they aren't, I won't be apologetic for "practicing" the Idaho Stop and I won't stop advocating for it.

* With regard to exchange, this is from a review from Green Electronic Journal of David Engwicht's Reclaiming Our Cities and Towns: Better Living Through Less Traffic:

Engwicht begins by examining the reasons he believes cities exist -- to maximize opportunities for exchange by concentrating people, goods, and facilities within a limited area. Transport should enhance exchange opportunities, but Engwicht finds that it sometimes does the opposite. Consider what often happens as traffic volume increases. First, new roads are built, or existing roads expanded, to accommodate the heavier use. Next, more space is designated for parking and housing the growing number of cars. As more space is taken by cars, opportunities for exchange, whether in the form of the corner store, the local playground or park, or someone's backyard, are soon affected. Stores move to the suburbs, children are transported to sports facilities to play, and people restrict their socializing to a smaller area of their neighborhood. Finally, with the distance growing between exchange opportunities, public transport becomes less feasible and, as a result, many people, particularly the poor, the disabled, and the elderly, are denied access to these opportunities.And today's Post has another article ("Cyclists explain why they sometimes ride on the sidewalk in downtown D.C.") on the topic, a followup by John Kelly to his article from last week about reckless cycling on sidewalks. But that's grist for the next piece.

Labels: bicycle and pedestrian planning, bicycling, car culture and automobility, change-innovation-transformation, demographics, media and communications, social change, sustainable transportation

2 Comments:

sidewalk cycling must be legalized in downtown DC. Safe and marked areas for cyclists need to be put into place where cycle tracks do not presently exist. Ways to implement this in an inexpensive fashion need to be explored. It should not need a super expensive re-engineering of the entire streetscape to work. Yes- it is not a solution to every street- but must be tried before it is denied.Yes- this is total heresy for anyone in the planning community to speak about.. sidewalk cycling is akin to breaking the most sacred taboos among planners and vehicular cyclists

This is a great post.

Wellbeing parts of everyday cycling have picked up consideration from the wellbeing division meaning to expand levels of physical activity, and from the vehicle and arranging segment, to legitimize interests in cycling.

Post a Comment

<< Home