Winning isn't everything when it comes to the value of (some) US sport franchises

Location, location, location; fans who still support losing teams; great stadium deals; and good media operations are key to high values.

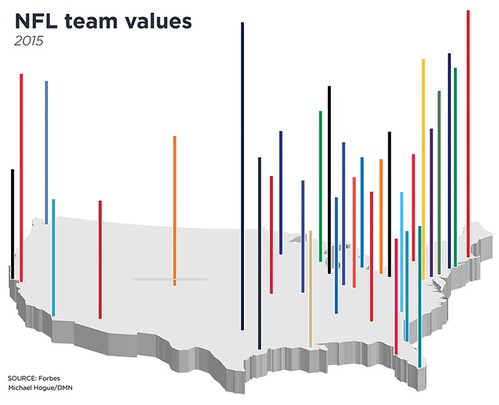

Based on data first presented in Forbes Magazine ("The Business Of Football;" "The World's 50 Most Valuable Sports Teams 2015"), the Dallas Morning News reports ("The soaring value of the Dallas Cowboys") that the Dallas Cowboys are the nation's most valuable sports franchise, despite not being successful in terms of win-loss records for many years. (This happens to be the topic of a current segment on "Real Sports with Bryant Gumbel"). The owner of the team, Jerry Jones, is also the general manager.

They chalk up the value to the remarkable stadium. Interestingly, the highest value teams tend to have newer stadiums which likely came with great deals and a lot of public financing. The Redskins too are highly valued, although their win-loss record is bad. The SF 49ers are highly valued--more than the Redskins--and have just moved into a new stadium in the Bay area, and are no longer located in San Francisco.

I've covered this broad issue in "An arena subsidy project I'd probably favor: Sacramento" and "Stadiums and arenas as the enabling infrastructure for "money-making" platforms," where I've made the point that since stadiums and arenas are the essential enabling elements of "teams as entertainment media platforms," when public financing is involved, there needs to be an allocation and realization of value made to the public purse in return.

2. In "An arena subsidy project," I discuss those characteristics:

- isolation or connection: how well is the facility integrated into the urban fabric beyond the stadium site and does it leverage, build upon, and extend the location and the community around it;

- size of the facility (baseball, football, basketball, hockey, soccer), bigger stadiums--football stadiums specifically--are harder to integrate in the urban fabric;

- frequency of events held by the primary tenant--baseball has 82 home games/year, football about 10 including pre-season, basketball and hockey have 41, soccer about 17--so football stadiums are very rarely used (according to the Chicago Sun-Times article "Emanuel mulling 5,000-seat expansion to Soldier Field," the facility holds about 22 events including annually, 12 non-football events);

- how many teams use the facility, maximizing use and utility of the building--for example, Verizon Center in DC is used by professional men's and women's basketball, hockey, and one college basketball team for more than 100 sports events each year;

- are events scheduled in a manner that facilitates attendee patronage of off-site businesses--a business isn't an anchor if it aims to not share its customers; the earlier events are scheduled, the harder it is to patronize retailers and restaurants located off-site, at night during the week, there is limited post-game spending as well, on the weekends it's a different story with more opportunity to patronize off-site establishments--teams manipulate scheduling to reduce spending outside of their on-site and 100% controlled facilities;

- use of the facility for non-game events drawing additional patrons--such as concerts and other types of programming; and

- how people travel to events: automobiles vs. transit--if automobiles are the primary way people get to events, then large amounts of parking usually in surface lots needs to be provided, making it difficult to foster ancillary development because of lack of land and poor quality of the visual environment, whereas if transit is the primary mode, then more land around a facility can be developed in ways that leverage the proximity of the arena.

Metropolitan trends: sprawl vs. refocusing at the core. I have to concede that these are criteria focused on those factors that favor in-city locations, especially communities well served by transit. In those regions still characterized by sprawl and where the "back to the city" movement is still anemic such as Atlanta, facilities are still moving from the city to suburban locations, whereas the professional basketball and hockey teams moved from suburban Maryland back to DC and the New York Islanders have moved from suburban Long Island to Brooklyn..

Also, there are different considerations for minor league teams in what we might call minor league cities and practice facilities (see "Sport team practice facilities and public subsidy (a practice facility for the Washington Wizards)"), such as the new facility being constructed by the Washington Nationals and Houston Astros in Palm Beach County, Florida ("Major-league celebration: Work on spring training stadium begins," Ft. Lauderdale Sun-Sentinel).

And for lightly used behemoth football stadiums, which in my opinion are better located in the suburbs than in center cities, at least those cities like Washington or San Francisco, where alternative uses for the space are likely to generate much greater benefits than what typically comes from football-related events.

3. From stadiums and arenas to sports districts. There is another trend with teams building allied multifaceted mixed use developments around the stadium/arena in order to generate greater economic term more days of the year. Staples Center in Los Angeles was the first and perhaps best example of doing this.

This is an evolution from what we might call "naturally occurring sports districts" like Wrigleyville adjacent to the Chicago Cubs' Wrigley Field in Chicago. In the naturally occurring districts, the economic benefits of proximity accrue to other property and business owners.

In the new iteration of districts where the properties (not necessarily all of the businesses within them) are owned by the same interests as the sports team, the team ends up capturing more of the ancillary revenue opportunities associated with the team and its events.

The way that the Washington Nationals stadium is anchoring a new Capitol Riverfront district and the way Barclays Center anchors the Atlantic Yards development in Brooklyn are more recent examples.

But compared to Staples Center, the Nationals aren't benefiting from the ancillary development--even though the owners are real estate developers, they don't control much in the way of other property around the stadium, while the lead owner of Barclays Arena, Forest City, is the master developer for the Atlantic Yards project, and will continue to benefit as it pursues ancillary property development adjacent to the arena.

Developments like Ballpark Village in St. Louis, a $650 million mixed use development built on the site of the old Busch Stadium, next to the new one ("Heading to Ballpark Village? Here's your guide," St. Louis Post-Dipatch), and Buffalo's HarborComplex built by the owners of the Sabres hockey team ("$200 million later, HarborCenter is among the city's biggest developments," Buffalo News) are examples of this type of ancillary integrated real estate development associated with sports teams in smaller cities.

And big "sports district projects" are underway in Detroit and Sacramento ("Dreams of a Hip, High-Tech Sacramento Hinge on Kings' New Home Court," New York Times) too. The arena district in Detroit is branded as "The District/Detroit" ("Display provides a glimpse into Detroit arena district," Detroit Free Press).

4. The increasing value of media broadcasting rights to sport teams. Earlier this week, it was reported ("New Comcast SportsNet deal for Wizards and Caps," Washington Post) that Monumental Sports, the parent of the Washington Wizards basketball team and the Washington Capitals hockey team, has bought into/received a portion of the Comcast regional sports television network for the Baltimore-Washington region.

Washington Post photo by Sarah Voisin.

While it is the case that the predecessor firm paid for the arena without direct public financing when it was first built, significant public investments in infrastructure by the DC Government were made in association with the construction of the facility, and later, admission tax rebates (technically a TIF) have been provided to fund arena improvements. Also, the city has changed signage laws to allow the placement of large video screens on the arena building ("Verizon Center's flashing billboards," Washington Post), which are used to market events and for advertising.

Labels: public finance and spending, sports and economic development, stadiums/arenas, tax incentives and abatements

5 Comments:

Some nascent thoughts (from February 2014) about your concept of the "space/arena" as the "platform" for the "content" of sports team:

While I would agree that is probably descriptive, isn't every physical building/structure a potential "content" platform? e.g. a school is an arena for learning; a university is a platform for advanced learning, research; a library is a platform for literacy, community; factories (such as they are these days) are platforms for manufactured goods. Who pays for these arenas/platforms?; who benefits?; who exploits; How should they be built/financed to achieve equitable outcomes for the entire community?

-EE

and how should they be planned.

e.g., while I argue that a library is a platform for knowledge, community, culture, media, etc., that's not how library systems typically conceptualize their mission or how they do facilities planning and programming.

I saw the economist for AvalonBay speak a couple years ago, he wrote a book on the economy and real estate development. He makes the points that buildings are envelopes for economic activity, that real estate development is merely a support function.

... but some of these questions are about the purpose of society, our social and economic relations (a la Marx) etc.

although there was a piece by John Kay in the Financial Times the week before about shareholder capitalism. He wrote that shareholders don't really own a company, that they buy an entitlement to a portion of the profit stream.

and in college I came across a body of work in the UK about "social audits" and developing a broader framework for the consideration of the role of corporations. It would be what is called "corporate social responsibility" now.

and it's probably where the concept of stakeholder as opposed to owner was first developed.

... I am trying to read a book on "social urbanism" which is what the people in Medellin and other countries call their approach to building civic assets as way to strengthen community trust and reduce violence.

The author cites the work of someone else, who writes a lot about violence and power. That author writes about four types of power-violence: social (intra-family, intra-community); economic; institutional; and political.

the author of the book on social urbanism attributes the change to a willingness (because they had no other choice) of the political and economic elites (a/k/a the Growth Machine) to give up some control of resources and systems because otherwise violence was out of control and it had to be staunched.

oops, I know Medellin isn't a country. That sentence should be "and other cities in South America and elsewhere".

I just learned many things about this topic and improved the sense of the readings. Thanks much

Dummy Dome Camera

Well written post! This article is really clicked in my mind and easily finds various resources. Thanks for sharing here.

Samsung Galaxy S7 Edge

Post a Comment

<< Home