Improving intra-city bus service in DC: a reaction to the DC Policy Center report on improving transit access East of the Anacostia River

Note that in my December postings on holiday buses and trains, I somehow missed the fact that DC's own Circulator bus system has a Winter Wonder Bus treatment of its own.

Note that in my December postings on holiday buses and trains, I somehow missed the fact that DC's own Circulator bus system has a Winter Wonder Bus treatment of its own.Separately from the WMATA story that I wrote about on Monday ("Improving bus service overall vs. reversing falling Metrobus ridership"), the DC Circulator intra-city bus program is going through changes too, after being evaluated in the 2017 update to the program's Transit Development Plan. The Washington Post wrote about it earlier in the week ("DC Circulator will get new buses, streamline routes").

And writing for the DC Policy Center, a unit of the Federal City Council, transit writer-blogger Alon Levy made recommendations for improving transit service in one of DC's primary transit-dependent districts, the Ward 7 section of the city (Improving bus service east of the Anacostia River).

Reading the TDP and the DCPC documents together, in line with my voluminous past writings on the topic, I'd say that the DCPC report raises some interesting points--ones I've made in the past, in particular how WMATA charges by mode so that a bus + rail trip = two fares--but fails to discuss the tensions between center city and suburban interests concerning transit which are beyond WMATA's control and which decidedly shape fare policies and practices.

And that the relatively low ridership figures for most Circulator routes suggest that maybe there are better ways to address transit needs with different kinds of services that better serve transit dependent riders.

DCPC report. (1) Makes the point that people ride buses because they are cheaper ($2) than riding Metrorail, which is especially expensive if it includes a bus ride to get to the station, since two fares are charged. People satisfice cost over speed, as Metrorail-based rides are faster.

(2) suggests that fares be lowered, modeled after intra-city bus systems like New York's--which don't charge two fares for rail + bus, provided you have a transit pass.

(3) Besides making suggestions for various route improvements, suggests an infill Metrorail Blue line station at Minnesota Ave and East Capitol Street SE (I think, the graphic isn't particularly clear) to make it easier to transfer between bus lines and the Metrorail Blue Line.

(4) Doesn't say much about Ward 8.

DC Circulator TDP. (1) The system has six routes: Georgtown-Union Station; Dupont Circle to Rosslyn; National Mall; Woodley Park to McPherson Square; Union Station to Navy Yard; Eastern Market to Skyland.

(2) The system has a $1 fare, which is half the cost of other area bus systems.

(3) Most DC Circulator lines have fewer than 2,000 riders/day, with one line, Dupont Circle to Rosslyn, at about 3,000 riders/day and the highest used route, Georgetown to Union Station at 5,500 riders/day. But because of the way the metrics have been set up, most lines meet the basic standard expectation of at least 20 riders/hour.

(3) The plan makes various recommendations on route changes to deal with low ridership and overlap with Metrobus services, and/or to serve other areas. Besides various tweaks, the major changes are to the Union Station-Navy Yard line, which shifts the line to Eastern Market to the SW Waterfront (Wharf development) and away from Union Station, and the Eastern Market-Skyland route, which will be shifted to Congress Heights from Skyland Center.

While not discussed in the report, typically high frequency bus services -- 5-6 buses per hour -- are delivered only on routes with high ridership, for example in the Metrobus system, that would be for lines with at least 10,000 riders per day.

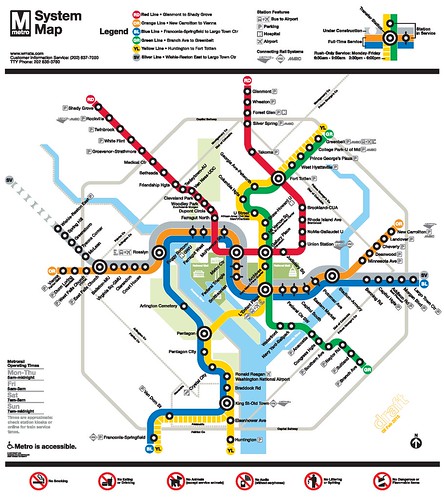

WMATA Metrorail map. There are 40 stations in DC and 2 on the DC-Maryland border, but which are considered Maryland stations.

WMATA Metrorail map. There are 40 stations in DC and 2 on the DC-Maryland border, but which are considered Maryland stations.Thinking about the transit system as a network. Based on concepts outlined in the Arlington County Master Transportation Plan, I outlined a network of transit services operating at and within the metropolitan area, at three scales:

(1) a metropolitan and regional network built on the subway and passenger rail program

(2) complemented by suburban and center transit networks;

(3) organized as three tiers or sub-networks: primary; secondary; and tertiary. These networks overlap and are not necessarily mutually exclusive.

For example, the metropolitan transit network is built on Metrorail but at the same time, I argue that the subset of stations in the core of the center city (31 stations, roughly from the Navy Yard station on the south, RFK on the southeast, Foggy Bottom on the southwest, and Van Ness on the northwest and Brookland on the northeast) along with certain trunkline bus services + certain Circulator lines, constitutes DC's primary transit network.

31 Metrorail stations at the core of the city

The DC or center city secondary transit network is the other 11 Metrorail stations and Metrobus services + the remaining Circulator lines.

And excepting certain kinds of shuttle services, the tertiary network is mostly theoretical, and is conceived as being intra-district/intra-neighborhood.

(The ideas behind the tertiary network concept are also discussed here, "Making the case for intra-city versus inter-city transportation planning," and theoretically DC Circulator bus routes are intra-district, but on a much larger scale than the framework suggests.)

The model for the tertiary network is the Orbit bus system in Tempe, Arizona. It provides intra-city transit between neighborhoods and main activity centers, complements the metropolitan bus and light rail system, and is free to use.

The Dash bus system in the City of Los Angeles operates similarly, but rides aren't free but still extremely cheap--35 cents per ride, and cheaper with passes.

Note that since my original writings on this, tertiary transit services are often termed, "microtransit," and can include "shared taxi/taxi collectif" and other kinds of shuttle and ride hailing services like Via or the Chariot service purchased by Ford Motor Company (see "A product in search of a problem: getting the right mobility product for the right market segment," 2016).

WMATA fare regime. The idenfitication in the DCPC report that the WMATA fare structure of charging two fares for bus and rail being a problem for low income residents isn't particular new nor pathbreaking.

But the policy goes beyond WMATA to the member jurisdictions and is in part the result of the hybrid system that Metrorail is, part commuter railroad, part subway.

When you prioritize access and also, transit as a transportation infrastructure supply matter (more people using transit means that fewer lane miles of roads are required, and less parking), fares are lower because you want to encourage transit use.

DC wants to prioritize access and lower fares, while suburban jurisdictions prioritize minimizing appropriations to the WMATA transit agency. This means that the two fare system remains in place and the fare structure is quite high compared to peer cities, where the structure of the transit system doesn't have elements of commuter rail.

From "What it will take to get WMATA out of crisis (continued)" (2016):

- Use of the federal transit benefit by commuters inflates the farebox recovery rate beyond comparable systems;

- Distance based-fares also inflate the farebox recovery rate compared to peer systems;

- WMATA charges two separate fares for bus+rail or rail+bus when most other systems do not, further inflating farebox recovery rates compared to peer systems;

- Combined, the comparatively high proportion of fare-related revenue has allowed WMATA to build a higher cost structure than would normally be sustainable compared to a peer transit agency;

- And until now, the comparatively high proportion of fare-related revenue has allowed the jurisdictions to pay less into the system than normally would have been required compared to peer systems;

- Fare pricing for revenue to reduce financing demands from local and state governments causes conflicts between DC and the suburban jurisdictions because of incongruent policies concerning transit use--DC is more focused on "transit as a utility" and as a preferred substitute (along with biking, walking, and car share) for car use and ownership, which requires a lower fare structure comparable to NYC or San Francisco's MUNI system;

- The [suburban] jurisdictions believe that they don't need to pay more money into the system than they are currently paying.

While rail fares are higher, bus fares are lower than most peer agencies. The one compromise between the city and suburbs is over the cost of bus service, based on DC's constant advocacy for lower fares. The base fare is $2, which is significantly lower than most peer cities, with the exception of Los Angeles and Baltimore.

Equity and low income transit fare products. I hate to admit that I have been remiss on this issue in the past. For example, my transportation wish lists in 2007, 2008, and 2015 (part 1, recaps the old lists; part 2) did not mention the need for a special transit pass fare schedule for low income riders, although I have written about this in other contexts.

Cities like San Francisco and Seattle/Puget Sound ("Seattle Cuts Public Transportation Fares For Low-Income Commuters," NPR) have specially-priced fare passes for low income riders. (Many systems also have free or low priced fare products for students, e.g., "Free Muni for low-income youth starts Friday," San Francisco Chronicle. DC, and Arlington and Montgomery Counties have youth transit pass programs.) The SF program does not include BART, but the Seattle program includes the regional light rail system.

Some bicycle sharing systems, such as DC and Boston, have extremely low priced memberships for qualifying low income residents, subsidized by participating organizations (DC's rate is practically free!).

And the Edmonton transit system has proposed introducing a "pay as you go" fare calculation system that would charge low income riders no more per month than the cost of a low income transit pass.

From the Edmonton Journal article "New smart cards for Edmonton Transit boast a 'social justice' edge":

People with steady jobs and good paycheques are the most likely to buy a monthly pass. They have cash on hand at the beginning of the month.Recommendations. Reacting to the DC Circulator Transit Development Plan and the equity concerns expressed in the DCPC report, Improving bus service east of the Anacostia River, I'd recommend a different course.

Those who might need their last nickel just to keep the lights on are the most likely to pay cash for every trip. It means they pay $3.25 per ride, more money for the same service.

That’s one reason Ken Koropeski is excited about Smart Fare.

With a card and an online account, the system can track how many times a person uses transit during a 30-day period, said Koropeski, director of special projects for Edmonton Transit. No one would have to commit to a monthly pass on Day 1. Instead, the system could automatically track use and once the rider hits that monthly maximum, all other rides are free.

“When you have capping, it has inherent benefits for people with low income,” said Koropeski.

Note: these recommendations would be in keeping with the recommendations in the Monday post, "Improving bus service overall vs. reversing falling Metrobus ridership," which suggests the best way to increase bus ridership is to reposition bus service as a premium product and by creating an integrated bus network across the metropolitan area, with a common branding system and other features.

Short term

1. Reconceptualize DC Circulator services into two types, higher ridership lines serving major activity centers or tourist districts, defined as part of the DC Primary Transit sub-network set of services (Union Station to Georgetown; National Mall; Dupont Circle to Rosslyn).

2. And the creation of a new type of intra-neighborhood service as part of the DC Tertiary Transit sub-network, modeled after the Tempe Orbit and Los Angeles Dash systems, focused on moving people between home, neighborhood business districts and transit stations and long distance bus routes, especially in the transit dependent areas of Wards 7 and 8.

3. For equity reasons, make the tertiary sub-network bus services free, which will address the cost disadvantage to low income and transit dependent riders resulting from the WMATA practice of charging separate fares to ride buses and the subway, even when the trips are linked.

(4. Note that ironically, Ward 3, the city's highest income ward, has some of the same issues identified by the DCPC report concerning the street network, bus lines, topography, and long distances to Metrorail stations, and so Ward 3 is likely deserving of a similar kind of intra-neighborhood transit service as well.)

Intermediate Term

It's not likely that impasse between the suburbs and the center city over the cost of fares, WMATA's distance based pricing system for Metrorail, and the practice of charging by mode rather than per linked trip can be solved any time soon.

5. Therefore, comparable to the Youth Transit Pass, DC should consider developing a separate transit pass product for qualifying low income riders, modeled after the Community Partners program for Capital Bikeshare and transit agency programs in San Francisco, Seattle, and potentially Edmonton, to be paid from social-human service appropriations, not funds normally allocated to transit.

The Orca Lift program was budgeted to cost about $7 million annually--$4.5 million in fare subsidies and $2 million in administration--and $3 million in one time costs for development, software, IT, and other costs ("Discount fares for low income riders will be offered," Seattle Times).

Because riding on WMATA costs more, such a program would cost more here, but even at triple or quadruple the cost, it's practically a rounding error in DC's $12+ billion annual budget, and should be considered on equity grounds regardless.

Long Term

Graphic from the DC Policy Center.

6. The DCPC report suggests an infill Metrorail station to better link Ward 7 and Ward 8 bus services to the Metrorail system.

While the diagram is unclear, it appears to be at Benning Road and Minnesota Avenue, which is very close to the existing Orange Line station at Minnesota Avenue, and not on the existing Blue Line alignment east from the Stadium-Armory Station.

At the cost of many hundreds of millions of dollars, that particular configuration is likely not supportable, although theoretically, an infill station at Minnesota Avenue and East Capitol Street may be worth considering, as it about 1.8 miles east of Stadium-Armory and 1.4 miles west of the Benning Road Station. It would still be a very high price to build. At the very least, the concept should be studied, and costs and benefits calculated.

Currently, the area isn't particularly dense, which makes it hard to justify the cost, especially given the likelihood of neighborhood opposition* to increasing population density/height of buildings to justify the cost of a new Metrorail station by leveraging the public investment in ancillary economic development.

========

* As a comparable example of likely neighborhood opposition to land use intensification, I don't understand why the report was produced/who commissioned it/that AECOM just did it on their own, but AECOM produced a report/conceptual vision plan proposing significant housing production in Southwest Brooklyn's Red Hook and Sunset Park neighborhoods and the waterfront, paired with a three-station extension of the 1 Subway Line, because they argue this area has the most opportunity to add housing units of any area in New York.

But the neighborhood reaction and response by local elected officials was not positive ("1 train extension into Red Hook pitched by engineering firm AECOM," AMNY), even with the proposed gain of new subway connections to the 1 Line in Manhattan and the F/G/R lines at the 4th Street/9th Avenue station, and the potential to connect to the D/N lines there also.

Labels: change-innovation-transformation, equity planning, infrastructure, transit, transit marketing, transportation equity, transportation planning, urban design/placemaking

4 Comments:

Again, going back to "mental models" or rather examples of "how government really works".

We don't have tools set up to get people to hospitals, or other socially beneficial activity, but we can keep bus fares low.

RAISING bus fare to $3 --then giving specific handouts to population groups that need it -- seems a better approach.

Likewise, you're right that as long as the feds are paying nothing it makes no sense to do a bus/rail integration.

(Another model -- which I am a fan of -- is follow the money)

"Today, because the fare system encourages low-income riders to take buses all the way from their homes to downtown D.C., many buses east of the river divert to Pennsylvania Avenue. The only bus that goes along the entirety of Minnesota Avenue, the V2, comes every half hour off-peak. Instead, WMATA could be running a bus down Minnesota and rely on connections to Metrorail and to high-frequency buses on Pennsylvania Avenue. With less branching, fewer meanders, and less need to run buses across the river, there would be room for much higher frequency on each trunk. Minnesota Avenue could get a bus every ten minutes off-peak, maybe even every eight minutes."

That is from the report and largely rings true.

Same with the DC-Union station circulator - people are going to Union station to save some $$.

... the federal transit benefit pays for either bus or rail. But I don't think that's what you mean.

It's to the advantage of the transit system for it to be legible. Likely it will be a little cheaper -- excepting the wage and pension issue -- if it is integrated.

The Raleigh-Durham way shows that the bus side can be integrated on a network and organization basis while still being comprised of legally separate agencies.

2. wrt follow the money. Yep. And it's possible that even with free intra-neighborhood bus service people would still take the one ride primary network bus because it's cheaper.

That's why I say subsidize transit for the people who need the subsidy.

AND YES, I have always argued the point you made about $3 etc. fares. People frequently argue against raising parking prices, etc., "because of the differentiated negative impact on the impoverished."

But then people who have the ability to pay pay less too.

Better to charge more, and provide subsidies to the people who need it, rather than leaving so much money on the table.

... but if you're charging a $3 fare, then you have a great pass system, have a maximum charge per day, and should have a great bus network.

SF area transit systems considering a discounted single fare price for low income households.

https://www.sfgate.com/bayarea/article/Bay-Area-s-transit-agencies-looking-at-fare-12822833.php

nice blog.

Post a Comment

<< Home