May is 2018 Historic Preservation Month: 59 ways to celebrate | Part 1: Items 1-16 (Learn; Get involved)

For many years, May has been designated as Preservation Month by the National Trust for Historic Preservation. Many state and local preservation groups organize events and programs during the month to call attention to historic preservation and its positive impact on communities.

This post is updated and expanded annually, to encourage us to acknowledge and celebrate historic preservation, ideally not only during Preservation Month but throughout the year, by pointing out things that we can see and do.

In the past I've run this as one very long post, which grows each year as I add items. Last year I started breaking up the post into thematic groups.

-- May is Historic Preservation Month: 59 ways to celebrate | Part 1: Learn; Get Involved (1-16)

-- May is Historic Preservation Month: 59 ways to celebrate | Part 2: Explore your community (17-33)

- May is Historic Preservation Month: 59 ways to celebrate | Part 3: Preservation at Home (34-40)

-- May is Historic Preservation Month: 59 ways to celebrate | Part 4: Cultural Heritage Tourism (41-59)

A preservation organization in Snohomish, Washington marching in a local parade.

Preservation Month aims to encourage increased engagement by supporters, and to reach broader audiences, in communicating the message that preservation is essential to community vibrance, identity, and quality of place. The National Trust suggests using its "This Place Matters" promotion program as a way to draw attention to historic properties.

-- This Place Matters Toolkit: How to Create a Campaign for a Place You Love, NTHP

Some organizations do a much better job of organizing activities throughout the month than others. Agencies that stick out positively include the State of Indiana Historic Preservation Office and the City of Boston Landmarks Commission.

Bringing media attention to preservation. It's also a great opportunity to try to engage local media on preservation topics.

For example, the statewide preservation group Indiana Landmarks releases their list of most threatened resources just before the onset of Preservation Month, as a way to get publicity and draw attention (see "Indiana Landmarks names '10 Most Endangered' sites for 2014," Indianapolis Star, "A new pastime: Preservation Month brings plenty of events in May in Southern Indiana," Jeffersonville News and Tribune).

(On the other hand, you can argue that releasing a list of endangered properties at another time of year may bring additional publicity to the cause outside of the May period when more attention is likely to be focused.)

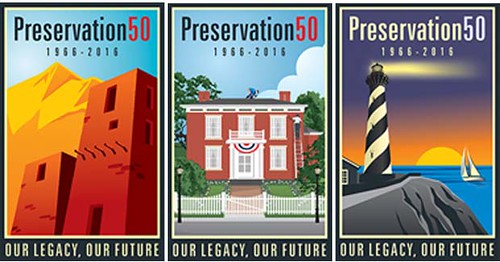

50th anniversary of the National Historic Preservation Act. 2016 was the 50th anniversary of the National Historic Preservation Act, which was passed in 1966. The law was spurred by public protest against the impact on existing neighborhoods from urban renewal and highway construction projects, "undertakings" funded for the most part by the federal government.

-- Preservation 50

Learn; Get Involved

1. Learn about the history of your community. For example, for DC, read Dream City: Race, Power, and the Decline of Washington, D.C., 1964 -1994 and Between Justice and Beauty, and more.

In DC, knowing about the original L'Enfant Plan and follow up planning by the McMillan Commission, allows you to understand the antecedents of the city, and make better land use decisions going forward, for your neighborhood and for the city.

Start with Washington in Maps by Iris Miller and Washington: Through Two Centuries by Joseph Passonneau. And see "Washington: Symbol and City," a permanent exhibit at the National Building Museum.

Start with Washington in Maps by Iris Miller and Washington: Through Two Centuries by Joseph Passonneau. And see "Washington: Symbol and City," a permanent exhibit at the National Building Museum.Many university presses publish books on local history and architecture that are well worth reading.

For example, the Wayne State University Press published a fabulous book on railroad stations, Michigan's Historic Railroad Stations.

The book, by Michael Hodges, doesn't have an extensive section of introductory text, but what's there is golden--a succinct discussion of public space and the importance of railroad stations in the civic realm, and a good survey of the key texts in the field.

Johns Hopkins University Press (catalog on railroads, regional interest, including architecture) and the University of Chicago Press (architecture) have extensive publishing programs on history and architecture, with many many excellent items. So do the MIT Press and Princeton Architecture Press, as do most university presses, from the University of California to the University of Tennessee.

History Press and Arcadia Publishing Company have extensive publishing programs on community history.

2. Become a member of your citywide/countywide/regional preservation organizations such as the DC Preservation League, the Municipal Arts Society in New York City, Baltimore Preservation, Historic Districts Council in New York City, Cleveland Restoration Society, Preservation Resource Center of New Orleans, Landmark Society of Western New York (which serves Rochester, among other places), etc. I am a big fan of the Chicago Bungalow Association.

3. Before you get too involved, you might want to take the time to read your city, county, or state historic preservation plan. This will educate you about preservation issues in your area. (Although generally such plans are pretty positive, and don't go into enough detail about the "threats" nor do they outline ways to address "opportunities" in a process design approach.)

In order to implement the provisions of the National Historic Preservation Act, the National Park Service was tasked with the responsibility of working with states to create a process for designating resources for the "National Register of Historic Places." All states have historic preservation offices to coordinate efforts at the state level. And in order to be "certified" at the state and local level--this means that the agency is eligible to use federal historic preservation funds--the entity has to have a plan.

-- DC Historic Preservation Plan

However to fully protect historic resources, you need local laws and regulations. Note that something that many people find confusing is that the federal law only concerns federal undertakings--federally-owned buildings (the Post Office is exempt) and federal programs spending money locally (like aging programs or road and transit projects).

Getting national recognition from the National Register of Historic Places for a local historic district isn't enough to protect resources from local, state, or private action. Separate local laws are required.

Unfortunately, I'd argue that the 50th anniversary of the law was an opportunity for assessment and evaluation, and setting an agenda for improvement, and in most places that did not happen.

4. Learn about why historic preservation is important, in and of itself, as well as a urban revitalization strategy. The reason I am a strong supporter of preservation is that I have come to believe that it is the only approach to economically sustainable neighborhood and commercial district revitalization that works for the long haul.

Hands down though, the best speech on the power and centrality of beauty and historic preservation in civic life is that by recently retired Mayor Joseph Riley of Charleston, SC.

Probably the best two books to read are Cities: Back from the Edge and Changing Places, in terms of getting up to speed on the issues quickly without having to read dozens of other tomes.

If you want to get into more detail, I suggest reading some of the work by Donovan Rypkema, such as his speeches, including "Culture, Historic Preservation and Economic Development in the 21st Century" and "Economic Power of Preservation," and his report on the economic value of preservation for New York, New York: Profiting through Preservation.

If you want to get into more detail, I suggest reading some of the work by Donovan Rypkema, such as his speeches, including "Culture, Historic Preservation and Economic Development in the 21st Century" and "Economic Power of Preservation," and his report on the economic value of preservation for New York, New York: Profiting through Preservation.The book published a couple years ago by the World Bank, The Economics of Uniqueness: Investing in Historic City Cores and Cultural Heritage Assets for Sustainable Development, extends these arguments more broadly.

5. Join a neighborhood/local preservation group, such as in DC the Capitol Hill Restoration Society, Historic Takoma, or Historic Mount Pleasant).

6. Nationally, you can join the National Trust for Historic Preservation while you're at it. If you join, you can visit NT owned sites and affiliate organization museums at a discount/free, get discounts at Historic Hotels, and discounts on products you purchase.

7. Preservation Action is a 501(c)4 advocacy group that advocates for specific legislation and is also a membership group. Their "Preservation Advocacy Week" is held in March, where members lobby Members of Congress for legislation favorable to preservation.

7. Preservation Action is a 501(c)4 advocacy group that advocates for specific legislation and is also a membership group. Their "Preservation Advocacy Week" is held in March, where members lobby Members of Congress for legislation favorable to preservation.8. At the state level, most states have statewide preservation organizations. In the DC-VA-MD area, that means Preservation Maryland and Preservation Virginia/Association for the Preservation of Virginia Antiquities, as well as the DC Preservation League. Many sponsor annual or bi-annual conferences, journals, and other provide other resources.

I am always impressed by the quality of the annual conference of Colorado Preservation. (The Saving Places Conference is in February, so we missed it.)

So join your statewide group.

9. Volunteer/1. Get involved in a preservation issue in your neighborhood or the city-county at large, which could include attending meetings of your local historic district/preservation commission, which in DC is the Historic Preservation Review Board, or working on a particular project affecting your neighborhood or city.

Issues common to many communities are inadequate protections for "old" buildings that may be historic but not necessarily designated (e.g., "Boston-area towns seek ways to slow razing of historic homes," Boston Globe) and teardowns, where older smaller houses are bought solely for the opportunity to build a new and bigger house on the same property ("Demolition Derby: As high-dollar houses crowd onto tiny lots, teardown fever is sickening neighborhoods across Nashville ," Nashville Scene) which is likely well located. This is an increasing problem in high value real estate markets, and less of an issue in weak real estate markets.

Median, Monument Avenue, with a monument in the background.

Another example is in Richmond, Virginia, where the Save our Statues organization is focused on restoring and maintain the city's statues, for example, those along Monument Avenue. See the article from the Richmond Times-Dispatch.

There are always issues with "old" commercial buildings being demolished in favor of new architecturally homogeneous buildings (e.g., preserving diners in Baltimore County, Maryland, or historic theaters in various places).

10. Volunteer/2, in a traditional commercial district revitalization initiative. A "division of the preservation movement" is the Main Street commercial district revitalization program, which links economic development with historic preservation focused on the revival of local commercial districts and downtowns in smaller communities.

There are affiliates in every state, in many provinces in Canada, and in other countries as well. In the DC region, Maryland and Virginia have state level programs--Baltimore's program at the city level is independent of the state program, and there are a number of Main Street programs in DC.

The Main Street Approach is ground up, where residents and other stakeholders join in with merchants and property owners to work on improving the commercial district overall. Typically, programs have a manager and may have additional full-time or most likely, part-time staff. It's volunteer.

Note that big downtowns and large business improvement districts tend to be members of the International Downtown Association, and are more focused on clean and safe activities and tend to be run by full-time staff, although in some cities such as San Diego, many of the business improvement districts are run using the Main Street Approach.

In my experience, interestingly, volunteers in Main Street programs tend to be 10-15 years younger than those in traditional preservation organizations, and the most active Main Street volunteers tend to live closest to the commercial district.

This makes Main Street commercial district revitalization programming a tremendous opportunity to draw new and younger audiences to the preservation movement.

There are more than 1200 Main Street programs around the county, including active programs in every state.

11. Work to preserve historic schools as schools. The DC Public School system has an archives and museum that is also a meeting center, Sumner School, at 17th and M Streets NW.

Sprawl-supportive building accreditation standards for school buildings push the concept of larger campuses served by school buses.

-- Historic School Preservation help page, NTHP

-- Why Johnny Can't Walk to School: Historic Neighborhood Schools in the Age of Sprawl, NTHP

-- Helping Johnny Walk to School: Policy Recommendations for Removing Barriers to Community-Centered Schools, NTHP

A tougher issue is preserving school buildings that are no longer needed. This is a big problem in large cities that once had much bigger populations and a large set of school buildings spread throughout the city to accommodate.

In stronger market cities the school buildings are in high demand for conversion to housing. In weak market cities, typically there isn't much demand for the buildings and they moulder, although sometimes they can be converted to social housing with the use of various tax credit programs. (See Why Vacant Schools Still Sit Empty, a publication of The Pew Charitable Trusts.)

12. Another way to learn a lot but very quickly is to attend a preservation conference such as the annual meeting of the National Trust for Historic Preservation (this year it's in San Francisco starting November 13th) and the National Main Street conference, which was held in Kansas City in March, some sessions materials are available).

13. Check out the history resources at your local library or a specialized collection such as in DC at the Washingtoniana Collection at the Martin Luther King Central Library or the Peabody collection at the Georgetown Branch, the Kiplinger Library at the Historical Society of Washington, the Jewish Historical Society, or the Moorland-Spingarn Collection at Howard University. Many city libraries have history collections.

14. Read a historic district brochure (or historic building or district nomination form). In DC, they are available online or in hard copy at the Historic Preservation Office. Many communities produce and publish these kinds of publications. Two of the best I've ever read is one on Jefferson County Indiana including Madison (One of the first Main Street communities) and Hanover, and the other on the Kansas City public market, called City Market. Both lay out their respective histories chronologically but thematically.

Relatedly, to win designation, the group organizing the creation of a historic district has to create a "context statement," which outlines the architectural, social, and cultural history of the area. While the writing quality varies, they are usually great resources and fun to read. One example is the nomination form for the Hyattsville Historic District in Prince George's County, Maryland.

The difference between a brochure and the full context statement is the detail. A brochure is succinct and the highlights version, drawn from the full document.

Also note that there is a variant of context statements, called thematic studies. These documents set the stage at a larger scale, that of the landscape, period, or a particular type of building, structure, or site (warehouses, schools, telecommunications facilities).

For example the National Register Publication Historic Residential Suburbs is an excellent discussion of suburban development, recognizing that this type was a part of late stage development within center cities also, at the outskirts but still within a city's boundaries.

The City of San Jose commissioned a Mid-Century Context Statement to document the city's "contributions to California Modernism, [focusing] on resources built between 1935 and 1975 ... [delineating] architectural styles, historic themes and associated property types, and catalogues local practitioners."

15. I am a big fan of reading the design guidelines publications produced for cities or neighborhood historic districts, which describe local historic districts, such as those from Montgomery County Maryland, Richmond, Virginia, Roanoke, Virginia, and the Philadelphia Rowhouse Manual.

The Roanoke Virginia Residential Pattern Book is a stand out!

16.. Listen to a preservation focused podcast. Podcasts--"radio shows" are a new addition to preservation-based media. Preservation Maryland produces a great series, PreserveCast, which is worth checking out.

Labels: land use planning, transportation history, urban design/placemaking, urban history

16 Comments:

Great speech by Mayor Riley.

He was lucky that a lot of Charlestown was already human scale.

Not sure how he would have felt about Uline, for instance.

But I think the larger point he makes are:

Memories

Public Space

One of the interesting things in the last few years is the hostility to HP by GGW and other millennial based groups.

Part of it is financial links to developers. Adopting supply side views on housing is also a part.

But I'd throw out is that in DC, we don't want to have memories, because it awakens latent white guilt about moving into the city and removing black tenants.

Puhleez.

There's no question $ makes a difference -- where you stand depends on who fills your pockets.

That being said, there's a huge disconnect between why the city is where it is today. I argue that preservation based placemaking saved the city. The thing is that the preservationists need to be flexible too. And the SGers need to acknowledge how and why what happened.

e.g., my story... I liked the buildings. Went on a road trip with a friend from college from Ft. Lauderdale to NJ. Realized in visiting places like Savannah that my neighborhood was no less beautiful, just different, even in the context of neighborhoods like Capitol Hill, Dupont Circle, or Georgetown.

I spoke at a class a couple weeks ago, met and talked with a young guy at a neighborhood library. Was asked what I think of H Street now? Sort of flummoxed me. I can't imagine anyone wanting the area to be like it was in 1987.

For me, gentrification and displacement is pretty complex, not much to do with HP. In the H St. area, so many houses were vacant, outside of rental conversion (including small four unit apt. buildings) there was little displacement.

The area was mostly black middle class, govt. workers. But the commercial district lagged considerably (most of -- there were pockets of bad s***) the residential part. It was a CD mostly serving people not from the area.

Even now, outside of HOPE 6 fueled displacement East of the River, much of the influx hasn't come as a result of displacement but from new housing, or people leaving the city. E.g., if there hadn't been new white and latino residents in W4, the population would have shrunk drastically in the face of black outmigration.

Maybe I should feel guilty but I don't. I chose to live in the city when trends and attitudes were absolutely opposite, and cities suffered from outmigration, poverty, and disinvestment.

People who came in the last 10 or so years are a completely different cohort. They did very little or do very little to improve the city, generally, although there are plenty of people who do contribute (such as all the various initiatives that have grown in the Petworth neighborhood as an example).

In the context of a city more than 200 years old, DC was majority black for about 50 years. Even my house has been only owned by white people since it was built in 1929.

OTOH, I lack the financial means to compete for housing in the new vastly appreciated market and am "protected" only because we already have a house.

The challenge, using the lGillette trope of "social justice" vs. architecture/place, is making the two congruent approaches.

Don't see why it isn't possible. But the SJ people expect total capitulation on every issue. There is very little interest in compromise and mutual satisfaction of multiple objectives.

yes about Charleston, but a couple weeks ago there was an interesting op ed in their local paper about the city's aggressive annexation program under Riley and how while it added to the property tax base, the new areas were much more sprawl oriented and less dense.

But yes, I've never heard a public official more eloquent than Riley on these issues.

He was big in the Mayor's Institute of Civic Design. But for me the problem with that initiative is that it needs to be deeper and "effect" legislators, not just the executive.

There just isn't consensus on urban design, design, what are the elements of a successful city.

All good points.

How do you respond to

1). MAybe HP works best in smaller cities (less than 100,000 people to pick an arbitrary limit;

2). Why does DC had so many landmarked/historic districts and is that good or bad?

FWIW, I think creating design review districts is the way to go. HP may be too much.

Part of the skepticism concerning historic preservation is it is so blatantly used as an tool by wealthy to prevent change and protect their interests. Groups use it because they can. Make a good narrative in your nomination package, and anything old can be spun as "historic". The most hilarious and infuriating example of this was about a decade ago in Alexandria where some poor homeowner had to appear before the historicism nannies because he took down a rusty chain link fence. The board was not ok with this desecration of the vernacular of the period, blah, blah, blah. The historic preservation movement had its time and place. It didn't preserve history per se, but it preserved a lot of urban form when it was most under threat. Today, urbanity is very much in demand. Historic preservation, as it is commonly applied today, serves as a counter to greater urbanity, and those who have the influence and the $$ can use it to those ends.

First, thank you for sharing and wrt "vernacular of the period," to me it all comes down to the "era of architectural significance." If it's congruent, fine, if not, not fine...

Anyway, I put what you say a little differently, but yes, too often HP is misused, I would say by anti-development interests, rather than the wealthy, but that's an element, sure.

Since you're in VA, there is a great book about the history of preservation in Virginia, _Preserving the Old Dominion_, and also the general book _History of Urban Places_.

Both discuss how HP is used by upper classes to define what history to codify, record and project, and the diminishment of other histories.

The thing is because in zoning law mostly HP is the only aspect of building regulation that "privileges" citizen input in a manner that doesn't occur when otherwise changes are "matter of right" and conform to the regulations.

===

so here goes with how I refer to what you described...

Preservation came to the fore when cities were declining, losing business and population, and neighborhoods needed to be stabilized.

Now that preservation has succeeded with that and helped to spur renewed interest in living in the city, some cities are in the position of being able to grow, and preservationists haven't figured out how to update their approach vis a vis the opportunity to grow, rather than being primarily concerned about stabilization.

I try to meld both. Not always successfully.

That being said, a friend-colleague who is on a planning commission argues that I am being theoretical, that advocates of today would still be against surgical intensification, because their natural inclination is to be against, that it isn't a matter of stabilization in the face of shrinking vs. growth.

=====

when trying to get the titles for those books, I came across this book chapter:

https://www.cambridge.org/core/books/evidence-and-innovation-in-housing-law-and-policy/historic-preservation-and-its-even-less-authentic-alternative/E6BEF89BE47FC05677A1B1321E98C5E3/core-reader

It seems to be worth reading.

The points you bring up are also worth writing up in an entry this month. Thanks. Hopefully I can get to it.

charlie --

neighborhood HP was created in response to change. Before that efforts focused on landmarks. Mount Vernon and Monticello were key examples.

Ironically, it was a response to the need to locate gas stations in commercial districts and neighborhoods. The idea took about 10 years to become codified into law (I think 1931, with the first historic district in Charleston).

Anyway, I don't agree with the idea of small cities. Because cities aren't monoliths. It comes down to neighborhoods-districts.

That being said, your point that design review may be more important than "preservation," is probably right.

I hate to concede it, but Glaeser may have a point. Not that he's right about setting an arbitrary number of buildings to preserve and removing restrictions on the rest. For one thing, it really only is applicable to super strong markets like NYC, Boston, SF, West LA County, DC and isn't relevant to most others, because they don't have the same opportunities for growth.

But where Glaeser might have some relevance is that because preservationists became so doctrinaire, integrating change, even done well, becomes very difficult.

WRT your DC question, I'd say -- again because we don't have design review, we don't have enough districts. I see some really bad work happening all around.

But the short answer is that HP was a response to Urban Renewal and freeway plans and DC had plenty of both.

The NHPA only pertained to federal undertakings and DC was then considered a dept. of the federal govt., so creating historic districts was seen as a key lever for protection. (Think about UR in SW, the SE-SW Freeway and planning for other freeways, and the post-riot "Project Action Committees" creating urban renewal plans for places like H St., Shaw, and Adams-Morgan + station area planning for Metrorail which was very UR oriented.)

Plus, in the early days of the law it was much easier to create a historic district. You just had to do a "sample," not a basic documentation of every building. And the approval process was much simpler. In short, most of the districts were created by decree.

Now that you have to do a "vote," document every building, and have to deal with 40 years of neoliberalism anti-government talk and how it has energized property rights discussions, it is almost impossible to create a historic district of substantive size in DC.

2. Note that the DC law was created out of a recognition that the national law only protects against national (federal) undertakings. That to protect against local acts, you need a local law. In part it was response to a church on Capitol Hill tearing down buildings for parking, with the justification that they couldn't afford to maintain "the old buildings."

This was cited in the Cambridge book chapter:

https://www.amazon.com/Information-Exclusion-Lior-Jacob-Strahilevitz/dp/0300123043/ref=ntt_at_ep_dpt_1

from the description:

Nearly all communities are exclusive in some way. When race or wealth is the basis of exclusion, the homogeneity of a neighborhood, workplace, or congregation is controversial. In other instances, as with an artist's colony or a French language book club, exclusivity is tolerable or even laudable. In this engaging book, Lior Strahilevitz introduces a new theory for understanding how exclusivity is created and maintained in residential, workplace, and social settings, one that emphasizes information's role in facilitating exclusion.

Thanks, the background on the DC law now is much more clear to me.

RE: Small cities, yeah good point that is a "neighborhood" effect.

RE: Glaesar. Outside of SF has any large city really managed to stop new growth/construction?

The primary effect of all the regulations seems to slow the pipeline, not stop it.

If you want to continue to drive capital investment into declining assets you need to make those assets expensive and valuable.

the trick is that the strongest markets need some intensification. (e.g., my arguments about the height limit)

This is necessary to respond to market conditions of the 21st century, rather than 19th and early 20th centuries, when legacy cities were mostly constructed.

The problem now in DC isn't just that the city has the opportunity to grow. It's that it was mostly built when the nation's population was slightly less than 40% of today's population. Plus HH sizes were much bigger.

SO there is a huge mismatch in demand vis a vis the built environment/housing stock.

That more than anything is the problem. We've been fortunate that multiunit has been added, mostly in ways that don't impinge on existing housing stock, and I think in ways that mostly complement neighborhoods.

Although plenty of people think the multiunit buildings on 14th St., U Street, H Street are travesties and ruin the city. Obviously I disagree.

Another problem is "overhousing." People living in houses "too big" relative to their need. (That includes my HH.) But it's difficult to carve out ADUs/accessory apartments, or the pay off is kind of long vis a vis the initial investment, it complicates mortgages, etc.

Then there is selective intensification and a lack of a means to shape it more directly, something I will write about in a follow up to the Mt. Pleasant piece, but something I've been meaning to write about in a couple different contexts for some time.

Then there is the opportunity cost issue for not building bigger, both vis a vis current zoning, and vs. allowing larger stuff.

... and the whole f* development stuff going on now. How anyone can credibly argue that by not building, housing prices will remain affordable, is astounding to me.

cf. https://www.flickr.com/photos/rllayman/26892701747/in/dateposted/

You do realize that it was the personal vision and philantrophy of one woman which saved and restored Mount Vernon, don't you? http://www.mountvernon.org/library/digitalhistory/digital-encyclopedia/article/ann-pamela-cunningham

-EE

Wasn't trying to avoid that, but I am more into the neighborhood preservation movement, not so much the preservation of individual landmarks, as important as it is.

As it happens, that too was sparked by a woman, Susan Pringle Frost, in Charleston. There is a book on her too, but sad to say I haven't read it (yet).

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=1BSCqcUurqw

Knowing what I have to do this month, I don't think I can get to it, but I really should try. It's deserving of an entry on its own.

In any case, the history of preservation is quite interesting and important to know about.

"...but I am more into the neighborhood preservation movement..."

My point was not to suggest you were avoiding anything. IMHO, it (neighborhood historic preservation, individual landmarking, history, etc.) is all inextricably intertwined, and in many ways dependent on individuals with the means, connections and energy to make what they see as the proper thing happen.

Another illustration about how the history of planning in the US has many elements that are women-related. Planning partly comes out of community beautiful/garden clubs, but also in the early period of codification (better housing in NYC e.g.) women were key players.

Post a Comment

<< Home