State versus local control of roads (and sometimes parks) sometimes comes down to money

In many states, major roads--primary arterials--are controlled by the state department of transportation while local roads are under control of communities.

This developed historically in part because of the way gas excise tax money is collected and managed, which is mostly done at the state level.

But managing arterials as part of a state-wide network often leads to conflicts when the land use context of particular stretches of roadway are atypical compared to how the road network is conceptualized and managed more generally.

When I first got involved in this stuff almost 20 years ago, I came across a publication from the Oregon Department of Transportation called Main Street: When a Highway Runs Through It, which provides a process and more detailed guidance for communities trying to work somewhat disconnected state highway departments.

Later, the Smart Transportation Guidebook was published by the Delaware Valley Regional Planning Commission, the Metropolitan Planning Organization for Greater Philadelphia. It was intended for use by Pennsylvania and New Jersey, but only NJ adopted it.

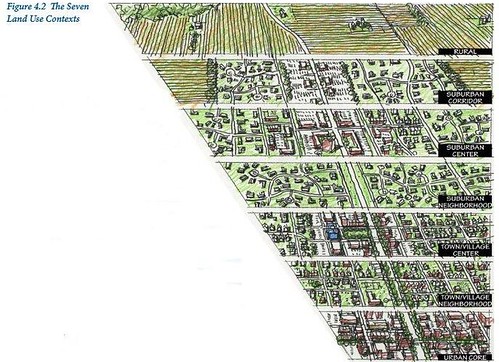

It has important discussion on managing roads in terms of land use context and the expectations that land use context set on roads in terms of expected speed of traffic, roadway characteristics, roadside characteristics, and whether or not the road is "community serving" or "a through road" used by motor vehicles to get to and from other places.

And, roads oriented to placemaking have higher urban design requirements and cost more to build and maintain.

Wikipedia photo.

Aspen, Colorado. This comes up because the City of Aspen is interested in taking control of its Main Street ("Who should own Aspen’s Main Street? The city or CDOT?," Aspen Times), because they wanted to re-time traffic signals in favor of pedestrians but now various elected and appointed officials are stepping back from this because they have reservations about taking on total financial responsibility for paying for a road at the level of quality that they want.

Takoma Park, Maryland. Similarly, but in reverse, a few years ago when reviewing legal documents concerning road ownership, the Maryland State Highway Administration discovered that part of the 410 arterial (mostly called East-West Highway, but in Takoma Park is called Ethan Allen Avenue and Philadelphia Avenue depending on the section) in Takoma Park had never been properly conveyed to the State, and therefore they wanted to push the financial responsibility of maintaining the road onto Takoma Park.

Wikipedia photo.

Eventually the State Highway Administration agreed to continue maintaining the road (Letter from SHA to the City of Takoma Park).

New Parks. Many cities, especially DC, aren't interested in taking on financial responsibility for maintaining and managing new park spaces.

DC even gave land away, to the National Park Service, for a waterfront park in Georgetown, rather than create a park that it controlled.

So in situations creating new parks, usually the city will maintain ownership of the land, but have a separate nonprofit manage and program the park and fund on-going operations.

======

Maryland SHA also has a guidebook on these issues, although it's more about the process, and doesn't provide detailed design guidance.

-- When Main Street is a State Highway

Virginia has a 2016 report:

-- WHEN MAIN STREET IS A HIGHWAY: ADDRESSING CONFLICTS BETWEEN LAND USE AND TRANSPORTATION, Virginia Transportation Research Council

Labels: provision of public services, public finance and spending, transportation planning, urban design/placemaking

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home