Schools #2: Successful school programs in low income communities and the failure of DC to respond similarly

Building on the previous post, "The bilingual Key Elementary School in Arlington County as another example of the "upsidedownness" of community planning," which makes the point community planning should focus on creating and maintaining great neighborhood schools as a fundamental anchor for strong neighborhoods, DC Public Schools just announced that it is ending its extended school year program for schools (called "Title I") serving primarily impoverished children ("District eliminates extended school year, invests more in classroom technology," Washington Post).

For all that has been touted about the DC "school education reform" movement, the reality is that it hasn't accomplished much, primarily because it hasn't directed the kinds of resources that are necessary to improve in substantive ways the outcomes for impoverished students.

In 2016, the Washington City Paper had a great cover story about this a couple years ago (cited in the entry "Fawning coverage of DC school "reform" doesn't push better practice forward"), making the point that very few additional supports and funding have been provided to the 40 lowest performing schools in the city.

For all the talk about charter schools, mostly they've proved that if you provide more daily instruction time, and with certain schools, longer calendars, so more instruction time, plus more resources, you'll achieve better outcomes.

But this finding isn't unique to charter schools. Many traditional school districts have figured this out also.

For example, Montgomery County Maryland has an award winning program for providing more resources to Title I schools, providing more resources to schools, teachers, students and families. They are building on this almost 20 year program by adding an extended year calendar starting this year ("Montgomery County Will Seek Extended School Years at Two Elementary Schools," Bethesda Magazine).

See "When ‘Unequal’ Is Fair Treatment" from Education Week. From the article:

When Jerry D. Weast became the superintendent of the Montgomery County, Md., public schools in 1999, he spent the summer poring over student-achievement results and demographic trends. Then he created a map to illustrate what he’d found.

The map divided the suburban district, just outside the nation’s capital, into two distinct areas, which he dubbed the “red zone” and the “green zone.” Most poor, minority, and English-language learners lived in the red zone, an urbanized core that was attracting a growing immigrant population. The green zone was predominantly white, affluent, and English-speaking. Academic performance closely mirrored the demographic trends, with the lowest-performing schools overwhelmingly concentrated in the red zone.

Without swift and deliberate action, the district faced the prospect of becoming split in two, divided by opportunity. To Mr. Weast, the solution was obvious. Montgomery County needed a differentiated strategy that funneled extra attention and resources to schools in the red zone, while increasing academic rigor for everyone.

“There’s this American thing about treating everybody equal,” he explained recently. “Our theory was, the most unequal treatment is equal treatment.”(A couple years ago, Bethesda Magazine published a great piece, "Hope Lives Here," on Daly Elementary School, a Title I school in Germantown, which covered in great detail the lengths to which teachers and school personnel go to help children and families.)

Why DC's extended year program failed: it was more like day camp. The biggest problem with DC's extended year program, a program that is successful in many other jurisdictions ("Powerful story of how Bristol Virginia elementary school deals with extremely impoverished students") was that it was poorly conceived.

A conversation I had with a DCPS employee last summer indicated that the program wasn't much more than the equivalent of "summer camp" with little emphasis on achieving improved instructional outcomes and growth.

DC's continued failure to provide different types of resources to address poverty in neighborhoods and schools. Comparable to how I argue that the problem with a disinvested property is lack of investment and the solution to disinvestment is not demolition but investment, the problems around teaching low income children aren't solved by forcing students to spend lots of time studying for and taking tests or to fire the teachers, but are solved by providing additional, focused and the "right" resources necessary to address economic and other gaps that make it much harder for children from such households to succeed.

I used to get furious in how former Chancellor Michelle Rhee was allowed to shift the argument from resources to teacher blaming, when just about any successful charter school is successful because they have more resources in terms of special programs, more instruction time, etc. For example, the Harlem Children's Zone model ("The Harlem Project," New York Times).

But rather than argue for more targeted resources and innovative programs for children and schools in need along the lines discussed in various past blog entries ("Creating cultures of excellence in schooling," "International Baccalaureate program at an impoverished high school in Seattle as a way to improve academic outcomes," "Back to school as a reason to consider schools issues comprehensively") along with extended year, the focus in DC has been on tests and demonizing "bad teaching" (and failing to acknowledge that "bad teachers" were produced by the system, and that therefore, the system has some responsibility for dealing with that, rather than tossing people out).

(Note that DC does have some of these kinds of programs, but they don't seem to be having the kind of positive effect amongst low income populations that they do when implemented elsewhere.)

Community Schools model as an alternative. A model for delivering an actual program for the "40/40" schools is the Community Schools concept, which is not new and pre-dates programs like the Harlem Children's Zone. It's about bringing to impoverished schools a wide variety of additional types of resources.

Austin, Texas is one place where the Community Schools model has been shown to be particularly successful ("Years Into Austin’s Community Schools Experiment, National Policy Catches Up," Texas Observer).

The initiative came at the instigation of the advocacy group, Austin Voices for Education and Youth.

According to the report, Community Schools: Transforming Struggling Schools into Thriving Schools, two previously failing schools, Webb Middle School and Reagan High School are succeeding.

From 2010 to 2015, Webb went from the lowest-performing middle school in Austin ISD, based on its test scores, to one of its best. Its enrollment has grown 55 percent, and fewer students are leaving the school mid-year. Reagan’s enrollment has more than doubled and its graduation rate has improved from 48 percent to 85 percent.The Observer says the report:

lauds Webb and Reagan’s discipline policies built on restorative justice, early college partnerships, daycare programs and mobile clinics for student mothers, new mental health and trauma support programs, on-campus English classes for parents, and new band, orchestra and dance troupes.And the Webb and Reagan schools are demographically comparable to the many school buildings that DCPS closed in Wards 7 and 8 ("Rethinking community planning around maintaining neighborhood civic assets and anchors").

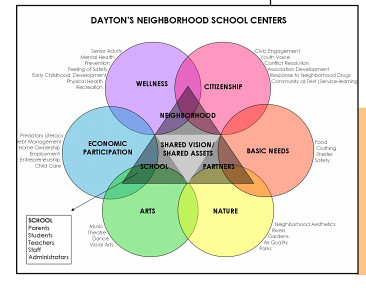

Dayton's Neighborhood School Centers. Dayton Ohio developed a community school program for five schools, which has since been expanded to include a sixth. Called "Neighborhood School Centers," it is a year round program involving multiple community organizations and the University of Dayton, offering 40+ additional programs to each school, serving children, youth, and families ("50-plus ways you can help 6 Dayton schools, thousands of students," Dayton Daily News).

Civic campus/co-location. Similar to the community schools approach is the co-location of multiple programs alongside a school. I'd call it a community or neighborhood civic campus. DC used to do a form of this in the 1920s and 1930s, but limited to schools, where typically elementary, junior and senior high schools were located contiguously.

One current example is from Austin, Texas, separate from the "community schools" approach, where Pickle Elementary School in the St. Johns neighborhood was built alongside a public library, recreation center, public health clinic, and neighborhood police station ("One-stop community - The challenge: Fill 5 needs for a Northeast Austin neighborhood The result: A smart and innovative building that does it all," Austin American-Statesman, 6/1/2003).

In Lincoln, Nebraska, the Moore Middle School was built in conjunction with a YMCA that provides community center and recreation center functions.

Family resource centers. Many schools have created focused family resource centers as part of their program to assist low income families. One example that impressed me is at Rothenberg School in Cincinnati ("Poverty surrounds OTR kids, doesn't define them," WCPO-TV).

Because of soaring need, half of the schools in Vancouver, Washington have added social services programming ("As need soars, schools rally behind families in Vancouver, Wash. — and other cities take notice ," Seattle Times). From the article:

These Family-Community Resource Centers appear to be making a difference, with attendance and graduation rates on the rise, especially among low-income and homeless youth. And while students living in poverty here still fall well behind their peers on state proficiency exams, their growth on district-level tests suggest the gaps could close soon.

The approach — which researchers consider promising, but not yet proven — could serve as a potential model for schools in Seattle and King County, where educators have dabbled with a similar program but continue to struggle with rising student homelessness and poverty rates.

... the district has pledged to expand Family-Community Resource Centers to all its schools by 2020 and has dedicated space for the centers in construction plans for new campuses. ...

In the years since Fruit Valley opened its center, student attendance and reading achievement have improved. Suspension rates declined, as did the number of students moving in and out of the school, a sign that families found some stability at home.

Financial Opportunity Centers, Kentucky. Another example, not connected to schools, is the Brighton Center in Northern Kentucky ("Helping people in poverty help themselves, WCPO-TV), which offers 37 different programs, in a comprehensive and integrated fashion, to help families become financially stable.

Mobile classrooms for summer learning enhancement. A more temporary enrichment effort is a mobile classroom in Cincinnati, which travels around the city in the summer ("Mobile classroom brings fun, learning to kids over summer vacation," WCPO-TV). From the article:

Learning shouldn't stop when school does -- especially not for children. The Cincinnati Early Learning Centers , which fight the "summer slide" by offering fun, educational activities for children, will hit the road this summer in a mobile classroom bus to bring that message to a larger audience than ever.Parent involvement. Chicago has a model program of parent involvement ("Lessons for locals on power of parents in schools," Seattle Times). From the article:

"The mobile classroom, of course, allows us to go to whatever neighborhoods desire the needs," vice president of CELC Outside Services Deanna Lane said. "Versus before, when we were in schools and in a classroom, we couldn't really move out into the communities."

The parent mentor program run by the Logan Square Neighborhood Association shows it doesn’t have to be that way. Over the past 18 years, it has recruited about 1,800 parents to spend two hours a day, five days a week for a semester or more in their children’s schools. ...

But Logan Square’s program goes further, installing a cadre of 10 to 20 moms and dads in each participating school on the belief that teachers in the longtime immigrant neighborhood would learn as much from parents as parents would gain from watching and talking with teachers.

“It is pointing the way for how schools can build much deeper, richer, more productive relationships with parents as collaborators in improving student success. It’s not just a series of random acts of family engagement, which is what you often see,” said Anne Henderson, one of the authors of a 2002 review of 50 studies of parent involvement. ...

The program starts out with a week of training that focuses on the parents themselves, encouraging them to further their own education and become leaders. That’s based on the belief that better-educated parents lead to stronger students, and stronger communities.

After the training, parents are matched with teachers who request mentors, although never their own child’s instructor.

Those who speak little English often work in dual-language classes, and those with little formal education are placed in kindergarten or preschool. The only requirement is that the parents work with students — not photocopy work sheets or grade homework.

Those who complete 100 hours in a semester receive a stipend of $500.

(This article from Northwest Asian Weekly reprints part of the article, with an appendix of similar but less visionary programs in Washington State.)

Conclusion. According to the book Developing Community Schools, Community Learning Centers, Extended-service Schools and Multi-service Schools, these types of programs are categorized by the type and breadth of added programs (education vs. social services) to schools, whether or not families are included, or time to the school calendar.

It's not that DCPS hasn't implemented bits and pieces of such programs and specialized curricula like Montessori or I.B. here and there across the system.

But they haven't developed and implemented a comprehensive program. Especially directed to what they have already defined as 40/40 schools. From the Washington City Paper article "Left Behind: How Kaya Henderson Failed At-Risk DCPS Students":

... A 40/40 school is among the 40 lowest performing schools in the District. When she announced her plan, Henderson said her second-highest priority—“invest in struggling schools”—was to increase proficiency rates in those schools by 40 percentage points by the end of the current school year. Initially, DCPS defined “proficiency” according to the D.C. Comprehensive Assessment System (DC-CAS), designed to test mastery of English, math, and science according to local “content standards,” but it abandoned that metric after the 2013-2014 school year.What has prevented development of comparable stories of success in DC is the failure to develop, fund, and implement a real plan for improvement--asking and answering the right questions instead of the wrong ones.

Schools designated as 40/40 schools have certain traits in common: They mostly reside in parts of the city plagued by high crime, high unemployment, high rates of disease and mortality, and high numbers of single-mother households. More than half are elementary schools, which experts agree is the educational stage that is most critical to any future prospects for success in academics—or life. ...

As Kaya Henderson departs DCPS, the schools are nowhere close to the goal she set, with marginal or inconsistent gains in some schools, stagnation in some, and losses in others, according to a City Paper review of DCPS performance data. DCPS, after four years, still lists 10 of the 40/40 elementary schools as “priority” schools, meaning they still need “intense support to address low performance of all students” and require “special quality monitoring and professional development.” Six are labeled “focus” schools, meaning they need “targeted support to address large achievement gaps,” according to the DCPS website. Just five are considered to be either “rising” or “developing.”

Which is not surprising, given that investment in 40/40 schools has ranged from non-existent to inequitable to compromised, according to DCPS funding data, proficiency scores, budget experts, and education watchdogs.

Labels: capital planning and budgeting, civic assets, civic engagement, integrated public realm framework, land use planning, neighborhood planning, public education/K-12, public finance and spending

5 Comments:

https://www.edsurge.com/news/2019-03-15-this-school-was-failing-at-its-mission-to-graduate-every-student-then-it-opened-a-day-care?

For all that has been touted about the DC "school education reform" movement, the reality is that it hasn't accomplished much, primarily because it hasn't directed the kinds of resources that are necessary to improve in substantive ways the outcomes for impoverished students.

The reform wasn't just for low income and impoverished students, it was to get DC off the floor of school district rankings.

Are you aware of the Save Shaw Middle School movement? It is an effort by activist parents and some plain old activists to get the city to keep its promises to make the old Shaw Jr. High building into a feeder school for the three elementary schools in the Shaw neighborhood, instead of letting Banneaker HS have it.

I attended an informational event at the school my son is in the boundary for, which would feed into Shaw Middle School if it existed. Right now Seaton feeds into Cardozo, which is not acceptable, we'd rather do private or home school. Anyway, I bring this up because the people in that room fighting for Shaw Middle School would not have stuck around the city, or at least east of the Park, if it weren't for the school reforms and the changed educational environment that convinced middle class families not to flee the city.

It's a shame that this has to be done, that it is news. Of course schools with the greatest needs should get more resources.

https://www.washingtonpost.com/local/for-one-dc-couple-education-doesnt-stop-with-just-their-son/2020/09/22/579d0a20-fced-11ea-9ceb-061d646d9c67_story.html

Looked at the WP story.

Not everyone does well in a virtual environment. It's a learning style and it's a style that has been imposed on millions of students who may have other learning styles that this conflicts with.

The kid in the story has two college educated parents who live in the same house. That is HUGE. Schools, no matter how well or poorly funded, cannot make up for a stable, well educated 2 parent household.

In Dc the highest achieving schools don't necessarily receive the most funding per student- https://dcpsbudget.ourdcschools.org/

https://www.startribune.com/whittier-school-community-education-coordinator-leads-and-learns-from-neighborhood-kids/600207557/ (access via printfriendly.com)

low income school, big summer outdoor education program, community hub elements of the school.

Post a Comment

<< Home