Tear it down/Don't tear it down

Nigel sends us notice of an interesting article from the Schenectady Gazette, "Amsterdam: Development or demolition?," about plans for redeveloping an old manufacturing building (mill) into housing, in Amsterdam, in upstate New York. From the article:

The debate is not just about whether to tear down the building, it has become a divide between two factions of Amsterdam residents: those who believe change will come by adapting the city to attract new residents and private investment from the outside and those who want a good quality of life for the residents already living here.

Well, for one, I don't see how having an empty lot, and yet another loss of the region's architecture and history helps the quality of life of extant residents.

But this is in fact the number one conundrum of revitalization. The reason a community "needs" "revitalization" generally is because the local economy is defective/broken/declining. (In terms of cities and region, you can break this down according to submarkets/neighborhoods.)

The job of revitalizers is to work at fixing broken economies. The problem is that it is not a "one-strategy" kind of job. You have to apply many strategies and tactics simultaneously. And, if part of it has to do with working to reverse serious, often, multi-generational poverty, you are looking at extremely long time frames over which to measure success.

In regions that have been declining for decades--many Midwestern metropolitan areas have not grown much over the past 40 years and most cities in upstate New York continue to decline as well--you are more focused on stabilization, maybe you'd call it "running in place," or reducing the impact of shrinkage, rather than on real growth. In other words, relative improvement within a landscape of decline.

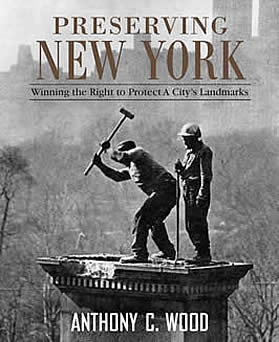

Right now I am reading the book Preserving New York: Winning a Right to Protect a City’s Landmarks, which is about the history of preservation there, leading up to the passage of NYC's local landmarks preservation law in 1965, and it is interesting in that the debates of the two different threads of preservation (patriotism, preserving the places where great historical events occurred vs. what the author calls "aesthetics" but what I also call the nexus of place, architecture, and people, a more "people's history") were present then, just as they are today, a long with the focus on "the new" and that by definition, "new" is always better. Maybe these debates will never be resolved.

The peak period of U.S. economic and manufacturing growth occurred during the creation of a mass market in the United States, and the period when U.S. manufacturers dominated the global scene. As the global economy further connects, manufacturing corporations in other countries have become economically competitive and ascendent if not dominant given the economic conditions of today.

The real problem, as far as revitalization is concerned, is that there aren't enough "good jobs" in the United States, especially for those with limited educational attainment, in the context of a global economy.

And that is something that no politician and no brilliant commercial district revitalization specialist can truly overcome.

Labels: commercial district revitalization, economic development, education, national economic competitiveness, urban revitalization

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home