(Most of the time) it isn't the technology, it's the process

There is a breathless press release ("Urban Planning Meets Online Gaming: NYU-Poly Introduces Betaville, Digital Tool to Revolutionize Public Planning") out from New York University, about a community visioning software program called Betaville. From the press release:

Betaville allows all stakeholders in a development project—from architects and builders to neighborhood residents — to participate in and influence the end result.

By fusing the technology that drives online games such as Sim City, where users interact in a virtual world, with the type of modeling software used by urban developers, Betaville aims to revise the traditional urban development process. Rather than a closed-door environment where near-final proposals are revealed to the public, the Betaville process relies on the continual refinement of a design through group participation. Because it is so easy to use and provides quick 3D images that can be viewed from many angles, Betaville will encourage early, collaborative change.

My reaction though is that the issue isn't the technology made available to all the potential stakeholders, it's the process. Not to mention that most of the stakeholders in planning and development matters prefer a somewhat static process with pretty narrow parameters.

Digital tools or access to them, don't change the underlying process, either from the government side or the developer side.

Just the other day, Philip Kennicott, the architecture critic for the Washington Post wrote a piece complaining about the National Park Service and a dog and pony show public "workshop" about potential security-related changes to the grounds and method of entry to the Washington Monument. See "Commentary: Washington Monument security plan didn't allow for public opinion."

He writes:

Although the meeting was well attended, Park Service officials announced that audience participation would be limited to a "workshop" format, with no opportunity for public questions or comment at the microphone. Several members of the audience, who came expecting a chance to submit input on the record about changes to how monument visitors would be screened before entry, vigorously protested the format, but officials refused to open the floor for comment.

"I've been asked to really push the workshop format," Timothy Canan told the crowd after several audience members raised their hands and asked to address the meeting. Canan, a planner with Louis Berger, an architecture and engineering consulting firm, led the meeting for the Park Service. Much of the official presentation was devoted to a technical explanation of the legal process for environmental and historic review -- which mandates public comment -- but involved no actual time for on-the-record public discussion. Instead the audience members were told they might address Park Service employees privately after a informational presentation on the design options under consideration.

No transcript of the meeting was created and Park Service official Stephen Lorenzetti said that the only way for public comments to be officially registered is online, via mail or on preprinted forms.

The workshop format is well used in planning and public administration circles. Basically, you set up a bunch of stations, on subtopics of the issue, and people go around and give comments. But yes, there aren't opportunities for the group to come together and for citizens to raise issues and get the audience engaged and supportive, providing the necessity for a response by the government people.

The book by Saint Consulting, Nimby Wars: The Politics of Land Use, is an excellent discussion of how to constrain the public process and/or how to shape the process better for the likings of various interest groups. But when you are limited to the workshop format, there is little opportunity to push the boundaries. (Saint Consulting was in the news lately over the disclosure that anti-WalMart campaigns are often paid for by supermarket chain competitors. See "Rival Chains Secretly Fund Opposition to Wal-Mart" from the Wall Street Journal.)

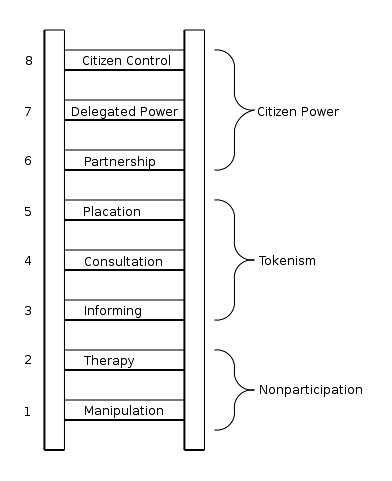

There is a classic article in urban planning about citizen participation, "A Ladder of Citizen Participation," Journal of the American Institute of Planners, 35: 4, July 1969.," by Sherry Arnstein (which by the way, isn't usually on the syllabus for intro courses in urban planning). Many of today's public processes would be graded pretty low according to this structure.

And I have been a participant on the other side, when the workshop method got hijacked by the citizens (see "DC Library Planning and Listening Session: A Bit on Last Night" and "John Hill, DC's new 'Reading Teacher'"? about a DC public library planning session in 2006) and in the H Street Transportation planning process in 2003--when I erupted about a really bad direction in the overall streetscape concept (I called it "urban brutalist faux shopping mall aesthetic" and it led them to abandon that direction for something that is proving to be much better as the streetscape is being constructed).

But getting back to the technology thing, it's just a tool. But the belief in the profession, ranging from Apps for Democracy type efforts to journal articles about how great the DC Town Meetings were under Mayor Williams, that technology is the cure fails to acknowledge that the control and constraints on the process are really more important.

From my disgust with groups like America Speaks (see "Can't seem to face up to the facts... or citizens/public meetings as 'arm candy'") comes what I call the Action Planning approach. This entry, "Social Marketing the Arlington (and Tower Hamlets and Baltimore) way," discusses the approach, although the idea continues to be further developed.

But I have to admit that the Action Planning approach has a fatal flaw too (plus it takes longer). It expects that everyone comes to the table with a basic consensus on some foundational processes:

- that public participation is a good thing

- that democracy is to be respected

- that participants also have a responsibility to learn and be knowledgeable about the matters at hand

- that it will take some time

- and that people will have to make some compromises.

I guess another lesson from this is that for the most part, zoning and planning processes and the rights involved with property ownership mean that development will happen. So it's best to shape that development in ways where all the stakeholders benefit to the greatest extent possible.

But action planning won't work when people don't come to the process with a commitment to that basic value set.

And it doesn't work very well when people have pretty mediocre expectations, or can be mollified pretty easily with bullshit and scraps (e.g., the Ward 5 people with regard to the John Ray and Vincent Orange led effort to redevelopment Florida Market; see "Florida Market destruction legislation hearing, Weds. October 11th").

Participation is both a right and a privilege, but at the same time, the public participation process can't be gamed by the government or the property owners either.

Labels: change-innovation-transformation, civic engagement, land use planning, participatory democracy and empowered participation, protest and advocacy, provision of public services

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home