The intersection of the rule for commercial district revitalization and the rules for restaurant-based revitalization

Interior, Uniontown Bar & Grill, Anacostia. Photo: Marvin Joseph, Washington Post.

Over the weekend, the Post had a nice article about the Uniontown Bar & Grill in the Anacostia neighborhood of DC, "Food, ambiance and a symbol of potential in Anacostia." The restaurant is an example of what I call Richard's Rules for Restaurant-Based Revitalization, of how approachable restaurants help drive revitalization of commercial districts by encouraging people to resample the area.

From the article:

Indeed, east-of-the-river residents are buzzing about Uniontown. But it's not just the food, late hours or ambiance of the 1,460-square-foot restaurant that has them excited. For many old-timers and newcomers alike, it has become a symbol of their community's potential to become a neighborhood with the same services and amenities found in more affluent areas of the city. A sign, they hope, of its rebirth. "Uniontown" is what the neighborhood was called when it was first developed in the 1850s.

"Every neighborhood needs a Cheers, and maybe this can be ours," said Tonya Kelly, 37, a consultant who recently moved to Congress Heights. She was at Uniontown with a group of friends opening week and marveled at the crowd.

But the article illustrates another point about revitalization that people often don't like to acknowledge. The reasons that neighborhoods and commercial districts fail is because at the micro-level, the economy is broken.

There are methods for improving neighborhoods and commercial districts through people-based improvement strategies, but they take a long time--decades--and the jury is still out.

While you need to implement proactive strategies to limit displacement and the negative impacts of high velocity change, neighborhood and commercial district revitalization is sparked in part by people with choices seeing value in the neighborhood, and their moving in and beginning the process of reinvesting in communities. (See the past blog entry, "More about contested spaces and gentrification.")

But in heterogeneous neighborhoods--where people may differ in terms of income, ethnicity, class, level of educational attainment, household and family type, sexual preference, level of religiosity, etc., even if they don't differ in terms of race--change is a very difficult and contentious process.

From the article:

Dasher and the community's other entrepreneurs are not without their critics. Anthony Muhammad, an Advisory Neighborhood Commission member who is Muslim, was concerned that Uniontown would be serving alcohol and challenged Dasher's liquor license, delaying the restaurant's opening by several months.

In an interview, Muhammad raised concerns that Dasher, who signed a 10-year lease, and some of the younger professionals who are moving into the area were not sufficiently committed to the area.

"We've seen people come and go before," Muhammad said. "I just would like to know how long she will be in this community . . . and whether this is the type of business, one that serves alcohol and is surrounded by four churches and a school, we need to embrace."

People do come and go.

And I get so tired of the restaurant/alcohol vs. school/church issue. For one, one of the unintended consequences of density and mixed use settings is that a variety of land uses are in close proximity. This can be a problem with "blue laws" regarding the consumption of alcohol and proximity to schools and churches.

For one, I would argue that laws with regard to church proximity and alcohol consumption are a violation of the first amendment to the US Constitution, and in any case, DC no longer has that restriction in its laws and regulations. But even so, churches are very quick to file protests against restaurants over liquor sales.

Even though for the most part, churches (and schools) are open when restaurants aren't selling liquor.

The real issue is how the consumption is managed. For the most part, alcohol consumption inside restaurants is much different than alcohol consumption that ends up occurring in the public space, usually abetted by the sales of singles and other single consumption alcohol products from Class A (liquor, beer and wine) and Class B (Beer and wine) licensed establishments.

Regardless, these kinds of oppositional movements occur all over the city in changing neighborhoods (H Street, Trinidad, Shaw, Anacostia, Columbia Heights, etc.) and it is incredible that in 10 years or more, we've gained little ground (other than the change in the law with regard to proximity to schools in commercial districts).

There is no question that without restaurants, you can't have successful commercial districts. And without the sales of alcohol, it's difficult for restaurants to succeed at the dinner business.

What's more important? A church that is active for a couple hours a week, mostly on Sunday morning, or a vibrant commercial district functioning 7 days/week? Similarly, schools close around 3pm, what is the deal with restaurant-based alcohol sales near a school, when the consumption for the most part is inside?

As I say, disinvestment isn't the only reason that neighborhood revitalization is so difficult.

It's also a matter of backwards-looking community leadership. What kind of business storefront do you want in your neighborhood? One like the Uniontown Bar & Grill, or the empty storefront below? Which is a sign of investment, and more likely to contribute to neighborhood and commercial district revitalization?

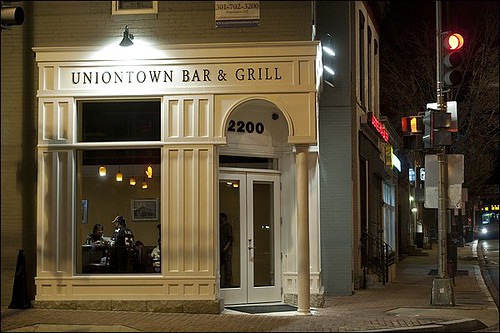

Exterior, Uniontown Bar & Grill, Anacostia. Photo: Marvin Joseph, Washington Post.

Imagine Your Business Name Here, Martin Luther King Ave. SE, Washington, DC. Photo from August 2007.

Labels: commercial district revitalization, gentrification, invasion-succession theory, neighborhood change, neighborhood planning, restaurants, urban revitalization

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home