Learning from Vienna and from Vienna's Social Housing Model

The latest piece in my series of articles on European cities for the Europe in Baltimore blog is on the social housing program in Vienna, spurred by an exhibit on the program at Baltimore's D Center. The exhibit will be traveling to DC in mid-November.

-- "The Vienna Model: Housing for the 21st Century City and its relevance to urban planning in Baltimore (and the US)"

Vienna has a number of interesting lessons for us, each of which is deserving of deeper treatment. I hope to write more about these topics on this blog over the next few months.

First, in Vienna, the municipal government (like Hamburg, Vienna is a city-state, which gives it more financial capital, and like DC, it is the national capital, which gives it a strong economic market for revitalization, although it's stoked by the role of the city in Europe and as a headquarters city for international organizations such as the UN) is the driver of the residential real estate market.

For a variety of reasons, the majority of the city's housing market is in rental housing, as much as 75% of the market. During the Socialist period from 1919 to 1934, the foundations for the city's municipal housing production and management program were laid, and more than 60,000 units, housing more than 200,000 people, were built during that time.

After a conservative-initiated civil war, Anschulss with Germany, and World War II, this program ground to a halt, but was revived again after the end of World War II. Today, the city doesn't directly construct new housing, but much of the housing that is produced is constructed as a result of city planning and financing.

A deeper presentation than available within the exhibit is available here: Housing in Vienna: Innovative, Social and Ecological; and one of the roundtables that helped shape the development of the presentation was written up in the Architect's Newspaper, “Roundtable: Housing in Vienna."

Second, Vienna, like many European cities, is focused on building new housing at the core of the city, for sustainability and other reasons. It's ironic that we say that's what we're for in places like DC, but the intra-city suburbanist opposition to pro-urban changes makes that difficult to attain here.

Instead, in the US, for the most part urban sustainability planning has focused on making cities "more green" rather than more urban, which is counter to the points made in the book Green Metropolis, which says that the reason that Manhattan borough of New York City is hyper-green is because even though the city imports water and food, it uses less energy per capita than anywhere else in the US, because people have smaller domiciles, for the most part they use transit instead of driving an automobile, and they buy less stuff.

Instead, in the US, for the most part urban sustainability planning has focused on making cities "more green" rather than more urban, which is counter to the points made in the book Green Metropolis, which says that the reason that Manhattan borough of New York City is hyper-green is because even though the city imports water and food, it uses less energy per capita than anywhere else in the US, because people have smaller domiciles, for the most part they use transit instead of driving an automobile, and they buy less stuff.I wrote about this in the context of the DC Sustainability Initiative more recently, "Realizing all aspects of Sustainable DC: it all comes down to chickens...," and I do intend to do a follow up in the context of the arguments of Green Metropolis.

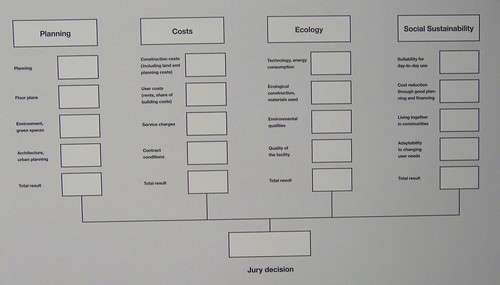

Third, to ensure that Vienna achieves the objectives in its master land use plan and housing plan, they have a detailed and rigorous planning process, including rigorous competitions for selecting developers and architects. They call this the four pillar process (pictured at right).

Fourth, I am really struck by how social and civic infrastructure elements are integrated into the Vienna social housing development program. It's much different from how planning is done in the US.

There are meeting rooms, day care, retail amenities, laundries, and depending on the development, even concert halls and cinemas, and a great deal of attention is focused on public spaces and the elements within them, although the creation of such infrastructure is not always easy--especially the retail, which isn't something that nonprofit social housing agencies seem to be very good at.

I am planning to discuss this general idea in the context of certain examples of revitalization planning in the US soon. In the meantime, this article from the Guardian, "Work begins on Drumbrae's new library, day care centre, and youth cafe," and this from the New York Times, "Next Time, Libraries Could Be Our Shelters From the Storm" give you an idea of the direction of the concepts.

Fifth, because Vienna borders the old "Eastern Bloc," it is situated to be able to take advantage of European integration but is also threatened by migration from Eastern Europe, were the city to be overwhelmed and unable to integrate new populations.

This is reflected in how they develop social housing, where they aim for social mixing, although they concede that it's easier to achieve in new housing developments, where all tenants come in to the development at the outset of its opening, and more difficult to achieve in older housing developments, where housing turns over much more slowly.

It's also reflected in how the European Union has facilitated cooperative planning, by bringing Vienna together with Bratislava, the capital of Slovakia, the Czech Republic, certain counties in Hungary, and other Austrian states to focus their attention on the joint development of their combined Metropolitan Area, in an initiative called Centrope.

It's sort of humbling to think of how difficult it is to get DC, Maryland, and Virginia to work together (the DC Metro Area also includes a couple counties in West Virginia, and the combined DC-Baltimore Metropolitan Area includes at least one county in Pennsylvania), because the three "states" share the combined Washington Metropolitan Area, whereas in Greater Vienna, it's bringing together four different countries, and the larger Metropolitan area is named for Vienna and Bratislava.

Sixth, like how Baltimore organized its cultural planning agency, the Baltimore Office of Promotion and the Arts into a somewhat independent city agency, but with the ability to do outside funding, and with protection from meddling, Vienna's realization of its economic development goals from support of the creative industries comes through a separately branded city agency, called Departure, although it doesn't have the same level of independence as BOPA.

Departure is another example of a government agency executing what I call "action planning" which integrates program delivery with planning, branding, process design, and social marketing.

Then again, so is Vienna's social housing program, which is organized through a single agency, Wohnfonds_wien, the Fund for Housing Construction and Urban Renewal.

Labels: action planning, civic assets, comprehensive planning/Master Planning, housing policy, provision of public services, public realm framework, public/social housing, urban revitalization

9 Comments:

"the intra-city suburbanist opposition to pro-urban changes makes that difficult to attain here."

More likely, its probably because as you mentioned in the beginning of the post, in that market 75% of the housing market is rentals, so households have less of a stake in change for good or bad. A homeowner is rightly concerned about the impact of change to their way of life and their financial well being.

That was something discussed at the presentation. In Vienna, they don't have the sense that renters participate less in civic affairs than residential property owners who occupy their homes.

I think the issue in general isn't that owners are more likely to be involved in civic affairs, although that is true.

I think it's more that we haven't built participation structures and systems that engage renters.

Because the Vienna piece was already so long, there was a lot I didn't write about.

One of the things they have are planning field offices, where architects, sociologists, and planners work together and engage in a variety of public planning processes.

Similarly, in HafenCity, they have a couple of "information offices" where planners work with the community on planning engagements as well. The offices also serve a public information function.

These kinds of endeavors assist in engagement, but of course, don't make it happen.

The IBA program engages in massive critical analysis of each iteration. The IBA_Haburg has published 7 volumes of analysis, including one specifically focused on civic participation and engagement.

It's volume 6 of the Metropole/Metropolis series: http://www.iba-hamburg.de/en/knowledge/iba-books.html

Again, many of the residents in the Wilhelmsburg district of Hamburg are not owners.

Vienna is, hands down, my favorite city in all of Europe. Also- of the large German speaking cities in WW2- it was not completely wrecked and only suffered about 20 percent damage to its center city .Much of the historic building stock remains untouched.

Hundertwasser is critical to all discussion on public housing ideas in Vienna

https://www.bostonglobe.com/2020/03/13/opinion/maybe-more-us-should-live-public-housing/

this article discusses mixed income housing, and social housing as"

Social housing refers to social ownership — an arrangement in which housing is owned either by taxpayers or a collective of residents.

Better yet, social housing is built to encourage integration between social classes. The mixed-income nature of Vienna’s social housing means that you’re just as likely to live next to a subway-car driver or a lawyer.

========

Thanks for the reference to Hundertwasser:

https://nasslit.com/friedrich-hundertwasser-i-give-houses-back-to-the-people-f9e59f4dc551

https://www.bostonglobe.com/2025/01/28/opinion/boston-housing-accelerator-fund-bunker-hill-complex/

In Vienna, most residents qualify for public housing. Can Boston combat soaring rents with the same model?

By offering a large proportion of the city’s residents places to live that are largely run, managed, and financed by the state. I’m not talking about neglected, dilapidated public housing like the kind you encounter in many regions of America — housing that too often concentrates poverty and violence.

In Vienna, well-maintained public housing complexes are distributed across the city’s neighborhoods and come with amenities like gyms, schools, and even shopping centers. Far from being places to avoid, these complexes housed more than 60 percent of the city’s 1.8 million residents in 2022.

The Viennese call such housing “social,” to reflect its broad usage — nearly 75 percent of the city’s residents qualify for it. This means that a supermarket cashier and a software developer can be neighbors, with each paying less than 30 percent of their income in rent. In Boston, only households making 80 percent or less of the city’s median income are eligible for Boston’s scant 17 percent of subsidized housing.

The HOC works because it is a revolving fund, meaning the HOC lends developers housing accelerator money to fund the construction of a building, with substantially lower interest rates than they would get from private lenders. Once the building’s units have been leased to tenants, the HOC refinances the project, takes a majority stake in the project to establish municipal ownership, and pays itself back for the initial loan. With the housing funds replenished and the HOC having collected interest from the developers, the HOC is better able to fund more mixed-income public housing. Montgomery County Council member Andrew Friedson says, “The Montgomery County housing fund started with $50 million and now it’s $100 million. This is one of the most cost-effective ways to create housing.”

With that formula for financing mixed-income social housing, more cities and states are warming to the idea. City officials in Atlanta and state officials in Rhode Island have announced plans to form their own public development bodies, and Boston’s housing accelerator fund is a step in the same direction.

Santana thinks this approach will yield dividends for the community. “In the United States, public housing has been traditionally viewed as this last resort for low-income families,” Santana says. “The stigma of public housing is tied to disinvestment and neglect. When you drive across the city and you pass a public housing structure, you know it’s public housing.”

Does Santana see a substantive difference between the terms “public housing” and “social housing”? “I think that ‘social housing’ reflects the philosophy that housing really should be a collective responsibility,” Santana says. “The term helps us reposition housing as a public good, rather than a commodity.”

Although that may be a tough sales pitch, Santana believes people are becoming more open to bolder interventions. “What I’m hearing constituents asking for, in all Boston neighborhoods, are options that provide stability; not just temporary fixes,” Santana says.

Maybe more of us should live in public housing

Economically diverse housing complexes, owned by the community, could answer the need for affordable units in Boston and other cities.

https://www.bostonglobe.com/2020/03/13/opinion/maybe-more-us-should-live-public-housing/

It’s a spritzing winter morning in Vienna and I’m standing, Hobbit-like, before a tower of greenery: baby spruce, gnarled vines, bushes that will bear flowers in a few months. They’re all exploding from balconies on one of the curved 27-story high rises that make up the Wohnpark Alterlaa — a massive housing complex built by a city-owned nonprofit and occupied by low-income and middle-class Vienna residents alike. Walnut trees, gardens, swimming pools, fitness centers, kindergarten classrooms, and even an in-house shopping mall and subway station are among the perks that Alterlaa residents enjoy, on top of their permanently affordable, rent-stabilized apartments.

This is one of the ways Vienna does public housing. Ever since the early 20th century, when housing shortages, grotesque living conditions, and rampant disease outbreaks brought Vienna to the brink of chaos, the city has embraced housing projects that can seem downright utopian if you’re a renter or aspiring homeowner in a city like Boston. Today, more than 60 percent of Vienna residents live in housing units owned and managed by the city government or nonprofits. They don’t call this public housing, however. Instead, the affordable housing stock here is referred to as “social housing.”

social housing is built to encourage integration between social classes. The mixed-income nature of Vienna’s social housing means that you’re just as likely to live next to a subway-car driver or a lawyer. You could hang out with them in your building’s centralized courtyard and catch up over a few bottles of beer, or you might bump into them at the built-in library. You’re each paying a quarter of your income in rent.

One of the reasons why public housing in America has often failed to flourish is because we’ve treated those units as a last resort for those with nowhere else to go. This model has concentrated poverty, further marginalizing the poor from the middle class. And, according to state Rep. Nika Elugardo, it reduces public housing to a top-down act of begrudging philanthropy, which is not the same thing as social ownership. “Our conception of public housing was sort of born out of a federal program for housing, and that includes a certain unhealthy dependency on national political dynamics for not only our housing funding, but our idea of what public housing even is,” says Elugardo, who ran for office on a housing equity platform. “We’re just chasing that funding. That’s a charity model of public housing. We need to shift to a local investor mindset, where the taxpayer is the investor.”

https://www.nytimes.com/2023/05/23/magazine/vienna-social-housing.html

Imagine a Renters’ Utopia.

It Might Look Like Vienna.

https://www.theguardian.com/lifeandstyle/2024/jan/10/the-social-housing-secret-how-vienna-became-the-worlds-most-livable-city

The social housing secret: how Vienna became the world’s most livable city

https://shelterforce.org/2023/12/19/how-we-can-bring-viennas-housing-model-to-the-u-s/

How We Can Bring Vienna’s Housing Model to the U.S.

Post a Comment

<< Home