Historic Preservation Tuesday: Historic preservation and public history: whose history is history anyway?

========

This is a reprint from March 31st, 2009. Slight edits...

========

There is no question that many people don't understand historic preservation of the "every day" -- preservation of neighborhoods -- in the same way that they understand the preservation of buildings, sites, and places that relate in some way to what we might call "the grand forces of history."

Remember that I call preservation of "every day" history the nexus of place, architecture and people (history).

The same kind of movement has happened in the discipline of history (historical studies) and the development of the subfield of "public history." According to the National Council of Public History, in the webpage What is Public History?:

Over the years as the field has evolved there have been numerous definitions of public history. Recently the NCPH Board of Directors described public history as “a movement, methodology, and approach that promotes the collaborative study and practice of history; its practitioners embrace a mission to make their special insights accessible and useful to the public.”

Public history is "where historians and their various publics collaborate in trying to make the past useful to the public." (See article below). That is, public history is the conceptualization and practice of historical activities with one’s public audience foremost in mind. It generally takes place in settings beyond the traditional classroom. Its practitioners often see themselves as mediators on the one hand between the academic practice of history and non-academics and on the other between the various interests in society that seek to create historical understanding.For me, the difference is communicated very clearly through two different newspaper articles. This morning's Post reports the obituary of Theresa Brown, the "Theresa F. Brown Dies at 86; Advocate for Preserving Historic D.C. Neighborhood" -- but the headline in the paper is better "Tenacious Protector of LeDroit Park."

She led the effort to stabilize and improve the LeDroit Park neighborhood of Washington, DC, one that had been home to the city's "upper crust" African-Americans for many decades, but had declined along with other neighborhoods in the city due to population loss and then the impact of the riots.

From the article:

Hammered by the 1968 riots and the flight of both residents and businesses, LeDroit Park took on a shabby appearance. Homes were left vacant, drug dealers moved in, and Howard University's expansion ate away at the edges of the area. Mrs. Brown, who worked for the old Chesapeake and Potomac Telephone Co. and was one of the first black women hired for its Baltimore office, told whoever asked that although she couldn't afford to live in the best neighborhood, she could work to make her own neighborhood the best. So she set to it.

She formed the LeDroit Park Preservation Society and began educating residents about their area's history. The tree-lined streets and landscaped traffic circles remained, as did 50 of the original 64 large homes, featuring beautiful tile roofs and gingerbread trim, expansive chimneys, iron grillwork, solid wood porch columns, bay windows and high ceilings.

In 1974, the neighborhood became an officially registered historic district. Some of her neighbors thought it silly, Mrs. Brown told The Washington Post in 2001. "I didn't care what the neighbors thought," she said. "There weren't enough of them to get in my way. I just kept going."

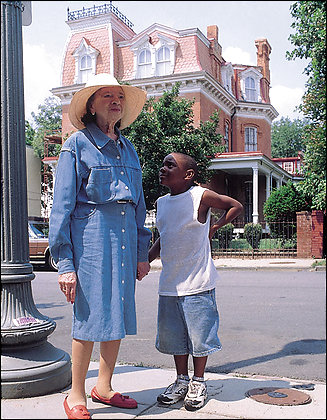

Theresa F. Brown poses with a child in her beloved LeDroit Park, a neighborhood filled with history. (By James Kenah)

I feel a kinship with Theresa Brown because we both got involved in our neighborhoods in the face of disinvestment, and in searching for strategies for improvement, we came to understand the value of historic preservation as the foundation of successful urban revitalization.

I met her in 2002, at the Annual Meeting of the National Trust for Historic Preservation, which was held in Cleveland. The year before, she received an award from the Trust, as a "Pioneer Preservationist."

I had talked to her on the phone once in 2001, when I was desperately seeking insight on how to present and portray the value of historic preservation in the H Street NE neighborhood.

I had applied for a grant on behalf of the Near Northeast Citizens group to begin a survey of the neighborhood. But opposition developed (at the time, I didn't realize that the opposition had been organized by supporters of the H Street Community Development Corporation, which did not favor preservation-based strategies). (She sent me on to her protege, Alan Rogers, who was very helpful.)

Amanda Rivkin for The New York Times. Some residents say the East Village is not as significant as other city landmark districts.

Then, there is an article in the New York Times, "Challenge to Landmark Law Worries Preservationists," which discusses how Carol Mrowka is suing the City of Chicago, because she believes "her neighborhood isn't a landmark." From the article:

Carol Mrowka considers her East Village neighborhood here attractive, comfortable — and ordinary. So when the city deemed the area an official landmark, Ms. Mrowka found it absurd and went to court.

“Sure, it’s a nice neighborhood,” said Ms. Mrowka, a real estate agent who moved 12 years ago to the neighborhood, north and west of the Loop, with its cottages and small, flat buildings that were home to immigrants in the late 1800s. “The basic style of the buildings is pretty, but this is not a landmark.”I didn't know about this suit until the article, but it would be pretty simple to lay out the argumentation in favor of the designation of neighborhoods as landmarks.

Simple bungalows in Chicago. Woodstock Institute photo.

And it is no surprise that "real estate" interests are fighting preservation, just as they did in the H Street neighborhood. Especially given that Chicago laws are very loose in terms of allowing teardowns of traditional buildings, and replacement with condos.

Preservation Chicago has called attention to this by including neighborhoods on its year to year lists of threats to preservation, the Pilsen Neighborhood in 2006, and the Sheffield Historic District in 2005.

And the Chicago Tribune has two incredible series of articles on how business interests run roughshod over preservation and neighborhood livability in the city, see "Neighborhoods for Sale" and "Squandered Heritage." [Active links to "Squandered Heritage" are in the right sidebar. "Neighborhoods for Sale" still works.]

But it does communicate very well this dilemma over what is and isn't history.

I think too often that people learned in school that history (and the process of research and writing also) is something that is not part of us, that we aren't part of history and we don't make history

That in a nutshell encapsulates the difference in approach to what historic preservation and history is and could or should be. History of "other people" vs. history of the every day, but history of the every day that explains and informs the history of urban development, and the creation and maintenance of neighborhoods, of transportation, of metropolitan regions, of architecture, of municipalities, etc.

And of course, we have the same dissension over this dichotomy in Washington. In fact, opposition to the survey effort in the H Street neighborhood in 2001 was an early instance of the kind of opposition we see as a matter of course in DC today, in places like Tenleytown (Armsleigh Park), Brookland, Chevy Chase, and Lanier Heights.

In the same vein as how do you record and recognize history, today's Seattle Times reports that "Jimi Hendrix childhood home torn down." One issue with "house museums" is that there generally isn't the interest and demand as well as the ongoing funds to maintain a "preserved" house, once it has been "saved."

Also see "'Uncle Tom's Cabin' Will Open to Visitors" from the Washington Post, about the preservation of a building in Montgomery County that was thought to be the place that inspired the book Uncle Tom's Cabin., [but it turned out that wasn't the case ("Turns out $1M 'real' Uncle Tom's cabin isn't the real one." USA Today).]

Or I remember when real estate interests put Brookland's Ralph Bunche house on the market at a price at least higher by $500,000-$800,000 than what the house would be worth as a place to live in... but the "exchange value" of the price difference in this case wasn't intended to go towards preserving history, but to the pockets of the sellers. (They weren't able to sell it at that price.)

Tough issues.

Labels: cultural heritage/tourism, historic preservation, public history, real estate interests, urban history

1 Comments:

Wow, what an amazing giveaway!! Thanks so much.

Post a Comment

<< Home