(DC area) Stadium talk a/k/a "football stadiums are a bad 'investment' for (big) cities

Visitors park at FedEx Field, home of the NFL Washington Redskins. (U.S. Air Force photo by Staff Sgt. Christopher A. Marasky)

I was impressed a couple weeks ago to read in the Washington Post ("Parris Glendening helped the Redskins move to FedEx Field. Now he wonders if that was a mistake") about how the former Governor of Maryland believes every time he drives past Redskins Stadium (FedEx Field) in Prince George's County, Maryland, that the final product was a signature failure in how the stadium fails to integrate into and improve the community around it. From the article:

So with another stadium battle looming, Glendening has a message for fans, team officials, and local politicians: that FedEx Field was doomed to mediocrity from the start. That there are fundamental issues with that stadium’s placement that cannot be erased, no matter what the team attempts to do. And that the next choice must be better.

“This is the mea culpa; I was actually part of the problem,” Glendening said. “It was just the wrong location.”2. However, even a good location for a football stadium doesn't have such a great outcome either.

Glendening pointed out how the team owner owned the property and was committed to that site, regardless of its lack of connection and transit access--the Metrorail system was extended by two stations in part to add transit system access to the stadium, which is 1.3 miles from the Largo Metro Station.

If there were regional land use regulations requiring that such uses (stadiums and arenas) be sited to minimize transportation demand impact, then communities would have some leverage in addressing sprawl.

In the Netherlands, they have that kind of land use and transportation planning framework. See "The ABC location policy in the Netherlands: ‘The right business at the right place’." But we're not the Netherlands.

3. Relatedly, last week's cover story, "A Safe bet?: The city has invested big in sports stadiums as development tools. Are they worth it?," in the Washington City Paper was about assessing the value of the city's funding of sports arenas and stadiums. They were equivocal.

This came up because of the recent finalization of an agreement between the city and DC United for a new soccer stadium at Buzzards Point ("D.C. United stadium takes a key step forward," Washington Business Journal).

... Which arguably will serve as a linchpin along the waterfront, better linking the area around the Nationals Stadium--called the Capitol Riverfront district--to the Southwest Waterfront, where the multi-billion dollar Wharf redevelopment project is underway.

I have come around somewhat on this general issue, but it is very much dependent on having the right plan and program in place from the outset to ensure spillover economic benefit. I came up with a framework for considering such decisions in a past blog entry.

The following characteristics are the start of such a framework, based on what shapes the ability to generate ancillary economic development as funding a stadium in and of itself doesn't provide enough public benefit to justify public funding:

- isolation versus connection of the facility to the urban fabric/built environment beyond the stadium site;

- size of the facility and its ability to be integrated into the urban fabric;

- frequency of events held by the primary tenants;

- the number of teams using the facility, maximizing use and utility of the building;

- whether or not events are scheduled in a manner that facilitates attendee patronage of off-site businesses;

- use of the facility for non-game events drawing additional patrons;

- how people travel to events: automobiles vs. transit.

5. Meanwhile, there continues to be a great push to plan for the return of the Redskins football team to the RFK Stadium site in DC, to a new stadium.

This scares the hell out of me, because the base cost these days for a new football stadium starts around $1 billion, based on the experience in Santa Clara, California ("Levi's Stadium: 49ers happy, Santa Clara may be on hook," San Francisco Chronicle) and the stadium under construction in Minneapolis ("New Vikings stadium will be named for U.S. Bank," Minneapolis Star-Tribune).

While such a location would be better in terms of transit access and would be in the city, I do not favor this idea at all, because for the most part, football stadiums don't generate very much in the way of additional economic development.

The point of public spending on such a facility is to promote additional economic benefits, not to merely support a particular form of consumption and entertainment. If additional benefits don't obtain, then there isn't a justification for public "investment."

"Community pride" -- the reason usually touted for public funding of sports facilities -- isn't enough.

There are some in-city locations where areas proximate to the football stadium seem to be doing okay, like Charlotte, NC or Seattle, but for the most part I argue the success of proximate areas is independent of any effect from the stadium.

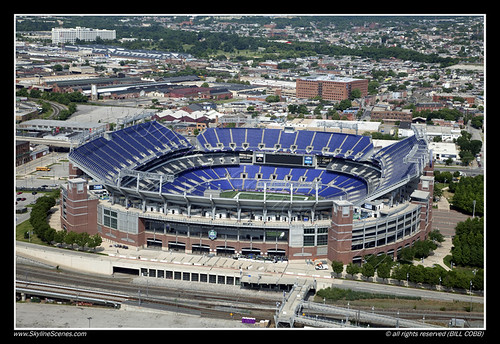

The Glendening article makes the assertion that the M&T Stadium for the Baltimore Ravens, located proximate to the Camden Yards baseball stadium does provide ancillary economic benefits. I don't think it does, but the game day experience is likely different and there is some additional benefit to local business. But otherwise, the big stadium is mostly empty every day of the year.

M&T Bank Stadium, Baltimore by Bill Cobb, on Flickr.

It is because of minimal use that I think it's better for cities to let football stadiums go to the suburbs, while focusing on keeping-attracting baseball stadiums and arenas for basketball and hockey because these types of facilities are smaller and can be better integrated in the built environment with positive economic spillover effects and experience much greater use.

And the likely movement of football teams to the Los Angeles market will yield a stadium shared by two teams ("Analysis: 2 teams needed to make Carson stadium profitable," Associated Press). The economic impact for the city is projected be about $3.5 million/year--not a huge return on a $1.8 billion facility.

RFK Stadium site, aerial view.

6. But because mayors don't like to lose out on such big projects, especially to the suburbs, Mayor Bowser of DC continues to angle for the Redskins facility. I'm happy for the stadium to shift from the Maryland suburbs to Virginia's suburbs ("Let it go: Washington Redskins and Virginia") because the economic tradeoffs between supporting urbanism in the city vs. reducing suburban sprawl are too great.

The city could reap much greater benefit from using the RFK site for housing and other uses. See the past blog entry "A park "is always preferred" by residents over development: proposals for a park on the grounds of RFK Stadium."

7. Because Richmond, Virginia is the home of the summer camp for the Redskins team and because the team is headquartered in Prince William County, Virginia already, the Richmond Times-Dispatch is covering the stadium issue almost more than is the Washington Post.

Their latest story, "National Park Service could be an obstacle to a new Redskins stadium" calls attention to the issues surrounding the underlying ownership of the land at and around the RFK Stadium is with the National Park Service.

The issue is that the city's use of the land is required to be "recreation oriented" and the stadium qualifies. In fact, for DC to use the site for other purposes NPS would have to agree to extinguish the recreation easement on the land, and the city would have to pay a big fee for its extinguishment--just as it did wrt McMillan Reservoir and the sand filtration site. The city could have received the land for free if it committed to recreational uses. Instead, the city paid $9.3 million in the late 1980s, to be able to have unfettered use.

In the meantime, I am happy to let the NPS issue cloud the desire to bring the Redskins back to DC.

Labels: building a local economy, public finance, sports and economic development, stadiums/arenas, urban design/placemaking, urban revitalization

2 Comments:

guess I have to agree with you on this one Richard- American football is very suburban/exurban and is not a city type game anymore as it once was. Baseball is clearly urban and has remained so. Football stadiums are super dependent on parking amenities- if you want to such a thing an amenitiey at all. Probably a majority of the fan base of the redskins lives in No Va anyway. They want it so bad- let them have it- but when they change the name stop calling them "Washington" whatever and hijacking our good city name and reputation...

This is an interesting post, it's shares information about football arenas are a terrible venture for urban communities.

Visit this site-Pharmacy Shop Online.

Post a Comment

<< Home