Transportation infrastructure as a key element of civic architecture/economic revitalization #1: the NoMA Metrorail Station

I became committed to switching to transportation planning after witnessing the impact of the creation of the NoMA subway station on the revitalization of the H Street neighborhood in Northeast Washington. I came to the conclusion that dollar for dollar, when done right, public investment in transportation infrastructure (especially when it is a part of a robust network) has the fastest and best return on investment in terms of spurring neighborhood revitalization.

-- "NoMa: The Neighborhood That Transit Built," Urban Land Magazine

-- Project Profile: NoMA-Gallaudet University Metro Station, Innovative Project Delivery, Federal Highway Administration

-- "NoMa's Transformation, Courtesy of Metro," Washington City Paper

The station was funded by DC, the federal government, and a tax on property owners with land west of the railyard, and was intended to support the intensification of this area into a business and office district. The station was created to provide even easier access to the subway system.

While the focus of the tax district was the western side of the Metro station, the station also impacts the eastern side. The reason I argue it was super important to H Street (people would argue with me, saying I don't understand geography) is because the Metro station changed the willingness of people with choices to live north of H Street.

A few years ago I calculated the increase in residential property value of about $200,000 per property on average. At 1,700+ properties, that was about $350 million--it's probably doubled now.

And that doesn't include the station's impact on the area north of M Street, which is being developed more intensively in a mix of commercial and high density residential, including north of Florida Avenue/Union Market.

In short, the economic impact of the station will be incredible, between $1 billion and $3 billion on the eastern side of the station--which wasn't even part of the original calculation, and many many billions on the western side of the station.

Note that other studies have found similar extra-normal economic effects from investment in infrastructure, such as the High Line Park in New York City ("The High Line Park and Timing of Capitalization of Public Goods") and Millennium Park in Chicago ("Millennium Park: 10 years old and an economic boon," Chicago Tribune).

Civic architecture. This isn't exactly a lesson about "civic architecture." Those come with the following pieces in this series.

As I have written in the past, the zoning changes allowing for big buildings in the NoMA district didn't come with special urban design requirements--although since then city has invested in public space improvements on 1st Street NE as well as bicycle infrastructure. And later the city agreed to provide $60 million or so to create parks and open spaces that weren't part of the original plan either.

Sadly, many tremendous opportunities to do integrate cool urban design and placemaking elements have been lost, at least in my lifetime, such as how an arcade could have been created as part of the Metro station and the buildings around it ("NoMA revisited: business planning to create community").

New York Avenue Metro station walkway

Nickels Arcade, Ann Arbor, Michigan.

Why the NoMA station worked and has had such high economic return. In Sacramento, a light rail extension was created to serve a newly developing area called Township 9, where the developer created a great station for the end of the line.

The problem is that since the line was created, little has moved forward in terms of new construction, and fewer than 500 people per day ride the trains, so the system is considering shutting down the line until the area becomes more developed ("Light-rail Green Line may shut," Sacramento Bee).

That's an example of building transit/transportation infrastructure to lead development forward. But it's much easier to do when critical mass has already been achieved. It's a tough decision to make about when to move forward on such projects. Developers want it early, when from a transit perspective that may not make sense.

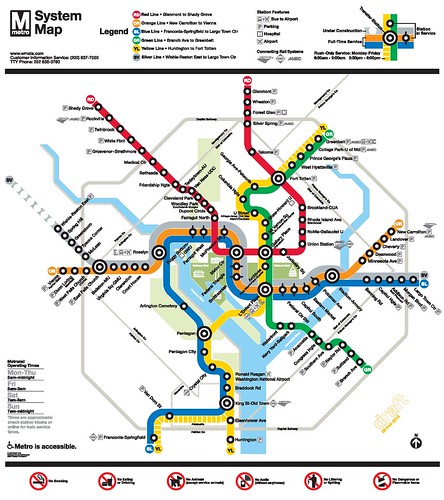

A robust transit network already existed. The NoMA station was different from Township 9 in Sacramento for a number of reasons. First, and most importantly, the WMATA Metrorail system is a wide scale network--at the time with 5 lines and 85 stations. The NoMA station was the 86th.

Since, the system has been further expanded with the creation of the Silver Line in Fairfax County and the addition of 5 stations, while a further extension into Loudoun County and to Dulles Airport is under construction.

The Metrorail system serves hundreds of thousands of riders. As a result the system is highly used, with about 700,000 daily riders during the work week--although the system's ridership has been on the decline because of operational issues.

Proximity to Downtown and the Height Limit. Because of the height limit, DC's business district spreads outward rather than "building up" as is typical of other cities, where buildings can be double, triple the size and even taller than the 160 foot base height maximum.

Since the area west of DC's central business district is mostly built out, it is spreading east (NoMA/H Street) and southeast (Wharf/Waterfront, Capitol Riverfront). The NoMA district is well positioned, being very close to an already developed and thriving Downtown, and is also served by train service centered on Union Station.

Note that in the city, commercial office space is most likely to stay centrally located, while transit oriented development outside the core tends to be residentially focused complemented with retail. (In the suburbs, commercial office space is shifting to a set of transit-connected business districts as well.)

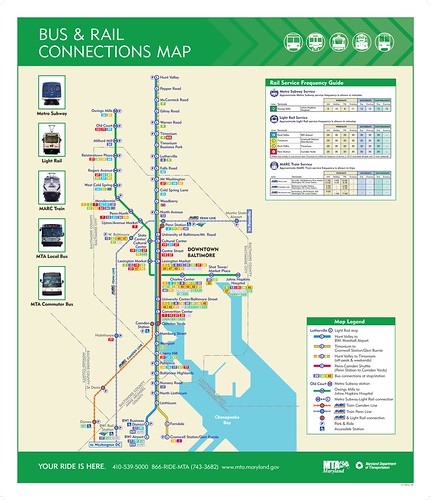

Baltimore as a counter example of the cost of not having a transit network. Having a network rather than a line or two is very important. A robust transit network makes locating around transit stations highly desirable. This increases the value of the land and supports intensification.

By contrast for example, Baltimore doesn't have a transit network, it has a couple lines which aren't well connected and need to be extended to have more value ("From the files: transit planning in Baltimore County"). About 80,000 people daily use the subway and light rail lines, compared to 700,000 in Washington.

Baltimore transit map. Most stations are in Baltimore City and Baltimore County, with limited connections to Howard and Anne Arundel Counties, and the there are limited inter-connections between railroad, light rail, and subway services.

That's why it's very difficult to move forward "transit oriented development"--intensified development--because sites next to transit stations don't increase in value because access to transit isn't seen as particularly valuable, while it would be if the transit system had more lines serving more places and people.

The one exception is the area around the Amtrak station, Penn Station, which is proximate to Downtown and two universities, and even there the process is slow ("Amtrak slow to move on Penn Station redevelopment," Baltimore Business Journal).

Just like with the long process around Penn Station, the State of Maryland has worked for more than 10 years to do TOD at the State Center campus, which is served by subway and within easy walking distance to the light rail ("The $1.5 billion State Center redevelopment is back on the radar screen," Baltimore Business Journal.

And Owings Mills Mall, touted as a great candidate for TOD and the endpoint of the western leg of the subway, has failed, although many state-funded TOD related investments have been made there ("Metro Centre at Owings Mills Office Building Rising at Transit-Oriented Development," press release).

Conclusion. The NoMA infill Metrorail station has been an economic development success of the highest order, providing the means to intensify development both west and east of the station, benefiting property owners, tenants, and residents alike.

But it's important to understand why this has been so, it wasn't like building the station was the equivalent of a magic wand. As mentioned the station was added to an existing robust transit network. Second, the area is well located, close to Downtown and Capitol Hill. Third, it's replete with transportation access--not just Union Station for railroad and inter-city bus service, and Metrorail and Metrobus, it also has easy access to I-95 north via New York Avenue and to I-95 and National Airport south via I-395.

Fourth, the city has been on an upward resurgence for 15 years, some business--DC is gaining retail, probably losing office, especially because of federal government agency contraction and moves out of the city, but lots of residents as trends have turned and now favor living in the center city. But even so the NoMA district has added some office, but not as much as developers expected.

So with those pre-existing conditions, dollar for dollar, when done right, public investment in transportation infrastructure has the fastest and best return on investment in terms of spurring neighborhood revitalization.

"When done right" is the trickiest element, and the subject of the following pieces.

There are lessons of what hasn't been done right from the NoMA experience, and sadly those lessons don't seem to have been captured and built into the economic revitalization and transportation infrastructure development process going forward.

That's especially true in DC, and true in many other places as well.

Labels: civic architecture, special tax districts, transit and economic development, transit oriented development, transportation infrastructure, transportation planning, urban design/placemaking

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home