The so-called myth that cities are growing when suburbs are still growing more

The other day, the New York Times ran a story, "Return to Cities an Urban Legend, Mostly," making the point that despite all the talk of population growth in the cities, more people are moving to and more growth is happening "in the suburbs."

I think this story misses very important points, a kind of "burying the lede."

Suburbs make up a much greater proportion of a metropolitan area's land mass and population. It should be obvious that as metropolitan areas continue to grow, more people live in suburbs. It should be clear why this is so. Compared to the entire land mass and population of a metropolitan area, the formal center city, such as Washington, Baltimore, Boston, New York City, etc., is but a small proportion of a metropolitan area's total population and land mass.

For example, the DC metropolitan area has a population of about 6 million. Less than 15% of this population is located in DC. DC comprises about 1.5% of the total land area of the metropolitan area (less when you take into account how much of the land is controlled by the federal government and not subject to development). Given these facts, it's unlikely that the city could capture a majority of population and economic growth.

New York City is part of a three-state metropolitan area greater than 13,000 square miles. The total population of the metro is slightly more than 20 million. New York City has about 8.5 million residents, in an area a cotch larger than 300 square miles.

What is significant first is that center cities are dense, with a large population in a small area. DC is about 60 square miles and has about 680,000 residents. The suburbs Fairfax County, Virginia and Montgomery County, Maryland are each about 400 square miles in size, and each has about 1.1 million residents. Each is about 6.5x larger than DC physically, with less than twice the population.

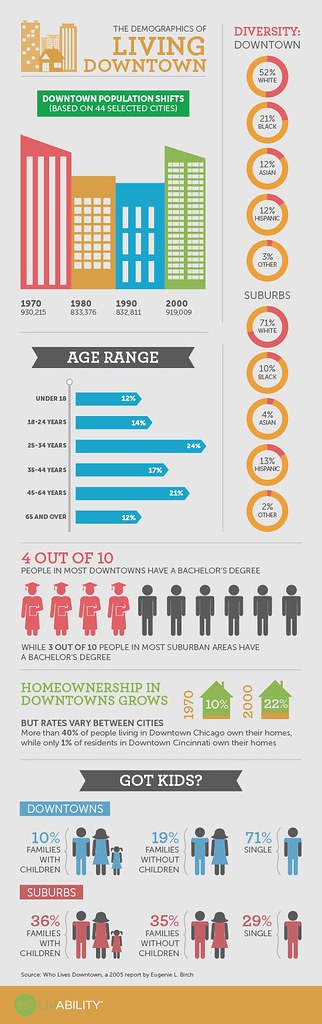

What is significant second, is rather than a story of center city shrinkage--which was the case from the 1950s to around 2000--there is a renewed interest in living and working in center cities, and center cities are capturing more residents and more business than they had previously. Since roughly 2000, there has been a change in demand for urban living. It's marginal, but significant enough to demonstrate significant "relative" levels of population in-migration, new construction especially of multiunit housing, etc.

Much of this in-migration has been centered upon downtowns or the "central business district," which has shifted from a unidimensional office canyon active only in the daytime to a mixed use district including a significant proportion of multiunit housing and night-time districts supported in large part by residents.

-- Downtown Living, Lincoln Institute of Land Policy, 2002

-- Who Lives Downtown, Brookings Institution, 2005

Downtown Living Infographic

This is true for most major cities, Chicago being an exception in terms of experiencing population shrinkage, but growth in terms of business headquarters capture.

Baltimore too is an exception, which is why I have suggested that Baltimore City and Baltimore County re-merge--they de-merged in 1851--becoming the nation's seventh largest city ("Baltimore Business Journal).

Interestingly, in DC specifically, we have been less successful than other cities like Boston or Chicago, in capturing large businesses relocating from the suburbs. E.g., Hilton moved from California to Tysons, and Choice and Marriott stayed in the suburbs with their moves/announced moves. A large Nestle division is moving from California to Rosslyn, not DC. (Although Caterpillar recently announced a move from Peoria to Deerfield, not Chicago proper, because they want easy airport access). Etc.

The suburbs are intensifying too. The NYT article does make a crucial point, that suburbs are moving to a newer stage of development that is confusingly also called "urbanization" in the academic study of land use.

The phenomenon called the "edge city" 30 years ago is moving to a new stage that is moving towards greater accommodation of transit and walking, more focused on developing placemaking qualities, and somewhat less automobile-centric.

This is demonstrated within the suburbs in how the "intensifying areas" are succeeding in terms of adding population and business activity, the more disconnected and car-dependent areas of these places are languishing.

The fact is that the market is bifurcating along the lines of concentration vs. disconnection. See "Continued Strength In Suburban Office Markets Dispels Myths, Bisnow versus "Big foreclosure suit ensnares suburban office, industrial buildings," Crain's Chicago Business. I have written about this in terms of the Fairfax County market, which is going through "reproduction of space" as a result of the Silver Line subway refocusing development in the Tysons-Reston Corridor.

With opposition. Although intensification in the suburbs is accompanied by a great deal of angst, as suburban residents often believe that suburban intensification is somehow a kind of repudiation of the "suburban ideal." See "End of free parking is the last straw for some Reston residents" and "In downtown Bethesda, residents and county debate whether more height is right," Washington Post, and "Reston: On a Collision Course," Connection Newspapers.

Suburban growth accompanied by growth in poverty and demand for aging services. Just as suburbs continue to capture "more growth," as suburbs mature they are capturing more poverty ("Suburbs and the New American Poverty," Atlantic).

When the original "unique selling proposition" of the suburbs was how center cities functioned as a metropolitan area's "poverty sink" with a disproportionate share of the region's poor, and the demand for social services to serve them. I used to call that reality a type of "quality of life subsidy" to the suburbs, one dumped on the cities, but now there is a turnabout.

-- Confronting Suburban Poverty website

-- Build a Better Burb website

-- First Suburbs Consortium, Greater Cleveland

Similarly, as people age, suburbs are forced to meet a greater demand for aging services, with limited financial means to address the need ("Aging in the American Suburbs: A Changing Population," Aging Well Magazine.

Center city proponents need to be conversant with the nuances. In any case, there are many ways to look at this issue, and proponents of center city primacy must be able to discuss the objective and subjective elements of the argument. A particularly good argument is presented by Steve Belmont in Cities in Full, which argues for "recentralizing growth" on the center city. And in some respects, that is what is occurring, with a lot of opposition from states, suburbs, and Republican legislators.

I have argued for a long time ("DC as a suburban agenda dominated city") that the people most traditionally active in local civic affairs in DC came to the fore during the period of the shrinking city when the priority was staunching outmigration and stabilizing neighborhoods in the face of trends that did not favor urban living.

Now that the city has the opportunity to grow in terms of population and business activity, people may need a different skill set and attitude, and also concern themselves with satisfying future residents, not just current residents, based on events and experiences solely from the past.

The digital economy renews the value of "agglomeration economies" Reading Richard Florida's new book, The New Urban Crisis, I wouldn't claim that this point was made as directly as it should have been, but it spurred me to think about how with changes in economic and social conditions in terms of the impact of digitalization and globalization, "agglomeration economies" have again become increasingly important.

"Agglomeration economies" is a fundamental concept from urban economics. The Geography of Transportation webpage at Hofstra University defines them thusly:

Agglomeration economies are a powerful force that help explain the advantages of the "clustering effect" of many activities ranging from retailing to transport terminals. There are three major categories of agglomeration economies:The job market and the world economy is much more competitive and operates much faster, making agglomeration or "clustering" valuable again when in the post-war period through the first decade of the 21st century, automobile-centric land use and transportation development paradigms allowed automobility to trump the clustering value of place/location.

Urbanization economies. Benefits derived from the agglomeration of population, namely common infrastructures (e.g. utilities or public transit), the availability and diversity of labor and market size;

Industrialization economies. Benefits derived from the agglomeration of industrial activities, such as being their respective suppliers or customers. This favors the emergence of industrial clusters;

Localization economies. Benefits derived from the agglomeration of a set of activities near a specific facility, let it be a transport terminal (logistics parks), a seat of government (lobbying, consulting, law) or a large university (technology parks).:

Transportation and agglomeration economies. Transportation efficiencies have always been the primary factor in the development of cities, starting with how most cities developed as ports on oceans, lakes, and rivers.

For example, wheat was milled close to where it was produced (Minneapolis-St. Paul) because of the cost of transportation. Heavy appliances like stoves and bathtubs were manufactured locally because they were "too heavy" to transport cheaply to other markets, etc.

The development of an integrated railroad system meant that businesses could transcend constraints on their ability to do business imposed by the difficulty and cost of transporting goods, and led to the creation of a unified national market and the consolidation of various industries.

Mills could locate far from where wheat was grown and no longer did every city need its own manufacturing plant for appliances.

It still wasn't perfect, because railroads didn't charge a flat rate for transportation of goods, they charged on the basis of the value of the product, so there was still a reticence to ship long distances goods that were particularly expensive.

The road network enabled--for a long time but not indefinitely--automobile transportation to trump the value of agglomeration. The creation of a ubiquitous and integrated road network serving local, metropolitan, regional, multi-state and national markets supported the rise of a deconcentrated land use and transportation planning paradigm, where uses are separated, and people mostly use a personally-owned automobile to get from place to place.

Cheap cars, cheap gas, the "open road" and plenty of free parking enabled the outward spread of commerce from center cities to the arterials and freeways of the suburbs with the creation of strip shopping centers, shopping malls, and business districts off freeways.

The carrying capacity of the road network is fixed. This works, at the cost of owning and maintaining a car, building and maintaining the road network, and at the economic, military, and environmental costs of a fossil-fuel based mobility network.

But it stops working when any of those factors/conditions change substantively, including the "carrying capacity" of the road network.

Richard Florida argues that as metropolitan areas reach a population of 5 to 6 million, an automobile-centric mobility network has decreasing marginal returns. (I believe that the writings of Newman and Kenworthy make a similar point.)

There is a line in the Jacobs book Nature of Economies, when she responds to a question of "Why aren't there enough roads?" with the response, "You're asking the wrong question. The right question is 'why are there so many cars?'"

Cities long ago recognized that the carrying capacity of the road network wasn't great enough to satisfy the various mobility and exchange needs of the cities and developed robust transit systems. According to a book review of David Engwicht's Reclaiming our cities and towns: better living through less traffic:

Engwicht maintains that cities were originally created as places for people to come together to trade goods and stories. A city, by definition, can be seen as a concentration of exchange opportunities. Cars get in the way of these exchanges in several ways. They drive people out of public spaces and create inhospitable environments for social interaction because of noise, fumes, and the barrier effects of the stream of traffic. Furthermore, they eliminate what he calls the "spontaneous" exchange — the unplanned encounter — thereby depriving cities of their essential spontaneity and life.Conclusion: The need to reposition economic development and governance systems around metropolitan areas. The issue isn't whether or not cities are growing faster than the suburbs but is the economic value of the metropolitan area and the necessity of strong center cities as thriving anchors of these places.

Traffic also sets into motion a wide range of self-reinforcing inefficiencies, according to Engwicht. Cars require roads, which require space, which require urban expansion, which requires more travel, which in turn requires more space.

This is the general argument of the Center for Metropolitan Studies at the Brookings Institution, that "metropolitan areas" -- that is center cities and the suburbs combined -- should be seen as the primary building blocks of the national economy and that US political and governance systems should be reformulated to recognize and support this reality.

Brookings laid these arguments out in the book Metropolitan Revolution.

See my review and also "Resurging cities, resurging metros, the impoverished and the Metropolitan Revolution (continued)" and "States, economic development, and sub-state/metropolitan area political restructuring."

In the meantime, the Trump Administration is doing all it can to screw cities in terms of proposals to defund transit, housing programs, health insurance programs, other poverty programs, etc.

And the DC area specifically, as the Trump Administration proposes significantly less money than is required to build new facilities for agencies such as the FBI and the Department of Homeland Security.

Labels: demographics, economic development, metropolitan areas, regional economies, regional government, regional planning, urban industry-manufacturing, urban revitalization, urban vs. suburban

14 Comments:

related:

https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2017-05-22/america-s-cities-are-running-out-of-room

This is what Florida writes about, and what works up people like Glaeser, Yglesias, and Ryan Avent on historic preservation as a constraint.

I agree somewhat. Obviously, except for places like Houston, city borders are roughly fixed. To add housing you have to intensify (cf. "The Growth Machine" argument).

I argue that (1) mostly we should preserve historic housing (2) but there are times when tradeoffs are appropriate, replacing historic buildings with bigger, (3) but mostly, if we are going to preserve housing that means we need to accept a surgical program of intensification

- in commercial districts

- transit station catchment areas

- that we don't lop off a floor or two of a building to make people feel like they are having an impact

- that we give intensity bonuses in transit catchment areas

- that we encourage promote ADUs, and depending on the size of the property, at least two units - in the house and on the property -- whereas the new zoning code only allows one

and very "difficultly" do some Arlington style rezoning, but very selectively. E.g., if you want a subway up Georgia Ave. you're going to need to rezone

- rezone some areas, like the RFK parking lots, for housing (this requires federal legislation so it won't happen)

- and have a dev. corp. in place to cure nuisances, and build on odd vacant lots (a related blog entry to come, using the H Street area as an example)

etc.

====

in the Post article on the ICSC, they quote some community organizer talking about that being a waste, that "development is leading to all kinds of displacement" etc.

That's actually pretty much not true, at least in DC.

What's leading to displacement, except for some exceptions, below, is an increase in demand to live in the city, which is driving up prices, and therefore "displacing" people as they can't afford rents or rental properties are converted to owner occupied.

But for the most part, new development isn't coming at the expense of existing properties. E.g., most of the multiunit buildings being constructed come at the expense of very limited numbers of housing units.

The exceptions are HOPE6 and its variants which made housing complexes smaller and added market rate housing. This did displace people directly and is one of the reasons for the rise in crime and other problems in PGC over most of the past 15 years. A big example is around the Stadium, which had been public housing. Or some of the developments in Ward 7. Or Ellen Wilson Dwellings in Ward 6.

There was some displacement with redevelopment projects like Clifton Terrace in W1 and as projects under HUD easements for 40 years came to the end of the program (e.g., the Community Preservation and Development Corp. CDC is set up to "preserve" affordable housing, not do do "historic preservation").

http://news.nationalgeographic.com/2017/05/climate-change-global-warming-drawdown-hawken/?google_editors_picks=true

interesting to note that a national magazine is promoting safe cycling infrastructure in cities and towns- this is really a first. Not the usual green platitudes-such as get your tires checked on your SUV to ensure good fuel mileage or get a green roof for your exurban McMansion. This was clearly written by someone who is with it. Maybe attitudes ARE changing...

Somewhat off topic:

Rating companies have put Illinois on a death watch. Granted this is more about politics than larger financial issues -- but there are reasons why taxes can't be raised enough to cover the gaps.

Also the Dallas pensions funds are in real trouble.

This is the Larry Littlefield point, but cities have a lot of pension issues. Unfortunately the reports don't include DC but given that WMATA's woes are the result of pension issues you can't underestimate this.

Also this:

"http://www.slate.com/articles/business/metropolis/2017/06/something_is_wrong_with_connecticut.html"

"But for the most part, new development isn't coming at the expense of existing properties. E.g., most of the multiunit buildings being constructed come at the expense of very limited numbers of housing units."

True, but the narrative is now that you can't afford to rent an apartment for 850 a month.

As I've before, the scandal isn't the DC prices; it is what you get for them in market rate units. The new supply is helping lot there -- AC, Washer, Dryer --but honestly for 1800 a month you can live in some pretty crappy apartments.

Again the amount of re-investment in older properties is so high that it can never be recovered in subsidized housing.

Thanks for the Slate cite, I'm going to write a short piece in response to the GGW piece on Brookland Manor... which is related.

2. wrt: but the narrative is now that you can't afford to rent an apartment for 850 a month.

when I first moved to DC in 1987 there was a lot of "group houses." I don't think there is anymore.

There was one house on the 300 block of Maryland Ave. SE in the early 1990s, where a room was under $300. (They didn't pick me though...)

2. I think I know what you mean by this:

Again the amount of re-investment in older properties is so high that it can never be recovered in subsidized housing.

but maybe not. Do you mind further explaining?

wrt pensions, absolutely.

2. analogous, there was an article in the WSJ about off balance liabilities in lease obligations for retailers masking actual debt levels. Now, sure, in bankruptcy a lot of those obligations can be shed.

but apparently there is a new GAAP coming that requires lease obligation debt to be recognized on the balance sheet.

I have to admit I've never read a CAFR (shocking). But pension obligations should be a required element.

Yeah I think in 2020 the new standards come into play.

I think you can make an argument that we are "right sizing" retails bringing it down to standard english speaking country standards (AU, NZ, canada).

that said, I was up in NYC and the amount of empty space on 5th, SOHO, very prime areas was shocking.

I have been meaning to write for a few weeks about all the retail issues and how three sets of changes are required:

- by the retailers

- by property owners

- by local governments

e.g., you clued me into thinking about the overvaluation of commercial real estate for tax purposes given the state of retail these days. That's one element of local government related changes.

otoh, DC seems to be able to hold its own somewhat. NYC is declining because property owners got really greedy, and businesses can no longer afford to pay super high rent/s.f. as a form of marketing, if there aren't concomitant high sales, e.g., the article in the NYT Thursday Styles section.

P.S., please don't forget this:

what exactly do you mean by this:

Again the amount of re-investment in older properties is so high that it can never be recovered in subsidized housing.

Nothing that complex.

Go back to Clifton Terrance.

If you remember the complaints back in the day, it was that it was falling apart.

Building depreciate.

Even if you can basically not have a price limit on maintaining stuff, the costs get so high it drags market value down.

(Look at the watergate co-ops).

If you are running it as low income housing, you know those costs are being cut to the bone, and the building falls apart.

What everyone wants to do then is go in, dump a lot of money in basically gutting the building, and then getting another 30 years of affordability.

Goes back to portfolio theory.

In 1995 Clifton Terrance was in the worse area. Now it is a very strong market area.

DC hasn't benefited from that rise at all.

You've got the difference in the urban poverty issues between the 1) lack of incomes and 2) lack of investment.

Cities can't do much about the income.

They can control the investment flows and make sure money is being dumped into those submarkets that need it.

(w 7 and 8 are the examples right now, see the various lawsuits re substandard housing)

I thought sort of that's what you meant.

Basically, every 30-50 years or so buildings need to be rehabilitated. The cost for properties that are "over used" like public housing is even higher.

And yes, since those rehabs are done at current prices, the financials get rejiggered to current prices.

(This relates to the point you made once about how theoretically, buildings should immediately begin to depreciate once they are constructed, but they don't... because of all those other elements of property value, especially "location, location, location."

... funny thing though wrt Clifton Terrace. I read the articles in the Post c. late 1990s about code enforcement in Columbia Heights as a way to displace, etc.

But then I worked the 2000 Census, including in one phase, _Clifton Terrace_, and I learned about "mothballing" etc. By that time, in what 6 buildings?, there were fewer than 40 occupied units.

The owners were aiming to recycle the property for a different segment of the market.

It made me really understand some of the nuances of revaluing urban property.

2. Relatedly, it's why "newly constructed housing" even as it adds supply, doesn't reduce the cost of housing, because it's added to the market at the highest cost, reflecting no physical depreciation, because it is constructed at current labor and materials costs.

I don't understand why that point seems to elude most of the activists who are denigrating new construction "because it isn't resulting in housing price de-escalation."

yes.

So in a roughly 10 year old condo, we are dealing with a small rodent issue. Fun weekend, poking behind cabinets.

Makes you understand the emotional need to go find a brand new building!

And the financing system is set up to facilitate that.

(opposite of un sustainable).

another example -- my preference is to buy a car and have it last 20+ years. My current one is almost 25.

I've realized in an DC level urban setting that won't work -- I need to really lease one every 3 years -- the damage from parking outside, scrapes, heat, vandalism, etc makes it stupid to invest in a old car.

that vs. "planned obsolescence."

I read an article in a home section of a newspaper from PA, about when to replace various appliances and when not to, depending on the nature of the repair, whether you should just buy a new one.

It said an oven lasts 10-15 years. Our gas stove in our house dates to the late 1930s! IT works just fine (although the oven temperature is a bit persnickety). Our dryer dates to the 1970s. Etc.

We bought a small fridge for our kitchen. The seal started coming loose after about 4-5 years.

2. Cars, yeah. Bikes too. I can see how living in the core, and close to a bike share system, that it would be great to offload storage, theft and damage, and repair-maintenance for $75-$95/year.

Post a Comment

<< Home