A comprehensive list of funding sources for arts and culture

Someone asked me if I'd written a comprehensive piece about funding arts and culture and I replied that I've written about it, but in bits and pieces across various entries. So I decided to take a crack at a comprehensive piece. I'm sure there are comparable lists published in manuals, articles, and textbooks.

The framework below doesn't count revenue generated by normal program activities such as ticket sales to events, fees from services, product sales, etc.

Note that there are four types of funds/donations/benefits provided:

- capital funds for facilities, which I tend to think about the most;

- ownership and access to facilities;

- general operating monies not earmarked for specific projects; and

- program-specific grants and sponsorships, which are usually time-limited.

- Government sources

- Individuals

- Foundations

- Corporations

- Real estate related revenue generation by nonprofit organizations

- Colleges and Universities

Government sources

Funding from Government

capital, facility access, grants

Cities,, townships and other forms of local government including counties, other government agencies, states, and the federal government.

- operating and other grants from general funds

- capital planning and budgeting for facilities from capital funding sources

- owner, operator, and sometimes lessor/rental agent of cultural facilities, libraries, etc.

- seller/lessor of buildings and land

In the past, DC hasn't been good about deed and other contract restrictions to get back control of properties that they sell when they are converted to other uses. Other governments have more public and transparent processes for grants, especially for capital projects.

General property tax "districts"

capital and operating

In many jurisdictions, schools, libraries, parks, even health, police, fire, EMS services, transit and various capital projects are funded by separate property tax related initiatives, which often require require special referendums/levies approved in a public voting process. (DC doesn't have this kind of process.) Illinois even has forest districts.

Usually these initiatives are limited to a city or county geography specifically, but can span communities when multiple jurisdictions are served by the entity.

Separately from regular funding sources, Seattle residents have passed additional levies to provide additional funds for programming, not capital projects, for libraries, transit, which is mostly provided by King County, and school and family programs.

For example, the school levy provides additional funding to ensure all schools have librarians, a nurse, and other structural support staff, the transit levy pays for additional bus service for Seattle specifically including new rapid bus lines, the library levy expanded hours and staff, etc.

Culture-related property tax districts that cover multiple jurisdictions

Capital, grants

Examples include the Regional Asset District in Allegheny County, PA; Scientific and Cultural District, Denver; Huron Clinton Metropolitan Parks Authority, Detroit area which dates to the 1930s I think; parks districts for an entire county, more recently multi-county tax support for the Detroit Zoo and the Detroit Institute of Arts each separately driven by Detroit's bankruptcy (unfortunately, I think they messed up in the Detroit area where I am from, the Regional Asset District is better, whereas in the Detroit area they are focusing on one institution at a time), library districts, etc.

The idea is that in the old days cities tended to own and operate these kinds of cultural assets, but with suburban out-migration there became many free riders and the cities no longer had the economic capacity to support these institutions by themselves.

For DC, along these lines I argue that we should change the property tax somewhat into tranches:

- general

- transportation

- parks and culture

- neighborhood investment

but it would need to be complemented with a public capital budgeting process generally and for cultural facilities specifically, which we don't do.

Yes in DC the Executive branch and Chief Financial Officer have capital budgeting units, but it's wrong that like the federal government, the public part of the process is merely just a part of the annual budget, unlike the much more rigorous review and public capital budgeting planning processes typical of most jurisdictions nationally and in the region.

Sales tax percentage add on dedicated to arts/culture

capital, grants

Prominent examples are ZAP (Zoo, Arts, Parks) in Salt Lake County Utah; the cigarette tax in Cleveland/Cuyahoga County Ohio. Great Parks of Hamilton County, Ohio; Metropolitan Area Projects, Oklahoma City

Note that speaking of equity, even though I hate smoking, I think the cigarette tax for the arts is wrong. The beneficiaries mostly don't pay the tax.

The MAP program is called Metropolitan but the tax is only paid by Oklahoma City residents, but then the projects are only within OKC too. It has to be re-approved every few years. Each "new" tranche focuses on a specific set of projects. It's in the fourth cycle I believe, so it's called MAP4.

MAP is an example of what I now call "Transformational Projects Action Planning." I need to read the former mayor's book that came out last year, although he didn't originate the program.

Even if they have to be renewed, the programs listed above are relatively permanent. A variant is a "temporary" sales tax add-on for a specific project. For example, the rehabilitation of the former train station in Cincinnati, Union Terminal, was funded through a small increase in sales taxes lasting for five years, for the entirety of Hamilton County, Ohio, not just the city ("Cincinnati's Union Terminal Now Saved for Future Generations," National Trust for Historic Preservation).

Most of these programs (including the ones mentioned above in Seattle) are very good about public marketing about the program, what is funded, and how it comes about because of citizen support.

Admissions taxes (on tickets)

source of funds for grants mostly, but could go towards capital projects

It bugs me that nonprofit arts groups argue for exemptions while at the same time asking for money. Or that sports teams ask for exemptions while getting millions in other funding. Etc. The only way that Prince George's County makes any money off the Redskins football stadium is because there is an admissions tax.

Advocates in the Hill District in Pittsburgh proposed a tax on arena parking to be used for community projects, but they weren't successful ("A dollar a car for the Hill," Hill District Consensus Group). I think it's a great idea.

A 5% admissions ticket tax is coming to Columbus, Ohio ("Columbus ticket fee proposal," Greater Columbus Arts Council)

Specific sales tax districts/local option sales taxes

for capital projects primarily, program support can be possible in some situations

States that stick out are Colorado and Georgia (Special Purpose Local Option Sales Tax: A Guide For Local Officials). But the Georgia districts I've come across haven't been related to arts/culture but revitalization and transportation. And in Colorado, unusually, these districts are usually smaller than a city.

E.g., there is a 1% add on sales tax in the Larimer Square district in Denver, called a historic preservation and restoration fee (rather than a "tax"). But it only covers a couple blocks total.

There are other special tax districts like this across Colorado, usually for revitalization projects functioning as a variant of TIF/tax increment financing (you sell bonds against anticipated future revenues) but using sales taxes, not property taxes, to pay off bonds and loans.

Tourism tax revenue stream

grants, capital projects

Sources include taxes on hotel stays, car rentals, restaurant meals, taxi trips (this can be diverted to transportation), sometimes parking (transportation/tourism). Airbnb type stays not paying such taxes crimps this revenue stream.

Travel industry organizations try to discourage such fees, which tend to be high, because they argue it discourages travel ("Tax burden on US travel and tourism," World Tourism and Travel Council.

For 15+ years I've argued that in DC some of this revenue stream needs to be captured in a more regularized fashion to support sub-city visitor marketing and cultural asset development and programming, out of the sense that if we make places great "for us residents" they are also attractive to others. Note that Events DC/Destination DC do a wee bit of this, e.g., providing some funding to Cultural Tourism DC, etc. But not enough.

Some jurisdictions do use this revenue stream for cultural development projects, not to just build and operate convention centers and run "convention and visitors bureaus" for tourism marketing.

Note that this should include funding in a systematic way for marketing of sub-districts of the city, like Anacostia or Georgetown, and DC doesn't really do that.

Special purpose property tax districts

operating funding primarily, but can support capital projects

The equivalent of business/community improvement districts but for culture/parks.

A proposal to pay for the operations of the High Line linear park through such a district didn't succeed.

Texas has lots of special purpose districts that fund the equivalent of BIDs/CIDs. Klyde Warren Park in Dallas was originally its own district, but later merged with the Dallas Arts District funding district ("Klyde Warren Park, Dallas Arts District reach accord on tax plan to fund operating costs," Dallas Morning News).

SF has what are called Green Benefits Districts at the neighborhood scale to support local green/open space activities.

Tax increment financing

capital projects

TIFs are districts/projects where it is expected that planned new development will generate new tax revenues. They sell bonds against the future revenue stream, which is usually made up of property and school tax revenue. They can be controversial because some entities like schools argue that their costs go up with more housing, but by not getting more revenue they lose out.

The revenues are used to fund infrastructure, sometimes to provide subsidies to specific developments, to fund other projects, and sometimes cultural facilities, public art, etc.

Allentown, Pennsylvania has a special type of district that also includes anticipated future state income tax revenues as part of the revenue stream. It's called the "Municipal Improvement Zone." That required special legislation from the state.

Bond support for capital projects

capital projects

Bonds issued by a government entity typically have lower interest costs and other better terms than a cultural organization can receive from traditional financial institutions.

DC already does this. Maryland has a program. Etc.

Individual organizational fundraising/ongoing campaigns

grants/donations, capital projects

This is the kind of fundraising we're used to and how the average citizen participates in arts funding.

We join groups as members, such as a museum, give additional donations, etc., to local and national groups, public radio and television, schools we graduated from, etc.

This category includes special fundraising events--dinners, galas, etc.

"United Way" for the arts

grants primarily, some capital projects

United Way is a workplace fundraising program, usually through large workplaces, where people make donations, sometimes matched by the workplace.

Mostly the monies go to social programs that donors either earmark to specific projects or provide a general donation, which the United Way then subsequent donates. United Black Fund in DC is a variant. There is the Combined Federal Campaign that isn't run by United Way and others.

In Cincinnati, ArtsWave is the equivalent of United Way for the arts. The original organization was created in 1949. These days it raises more than $12 million annually, which helps to fund 125 different organizations and projects, along with general arts marketing.

Capital/endowment campaigns

capital projects, endowed programs (e.g., a professorship, scholarship programs, etc.)

Heavy duty campaigns to raise millions and billions such as university fundraising campaigns, hospitals, etc. Or in the DC area, to fund expansion to Arena Stage, build a new Children's Museum, etc.

Note this is a hybrid category because foundations also may provide support to such campaigns.

High dollar funders ("rich people") who often have their own foundations

grants, capital projects

Large donations are often associated with naming rights of some sort.

I'm thinking of people like Eli Broad in Los Angeles. Major funding of LACMA, Museum of Contemporary Art, but also created his own museum. But his museum is free and well located and easily accessible downtown.

Mitchell Rales (Danaher Group), created the Glenstone Foundation art museum in Montgomery County, Maryland but unlike Broad, the museum is not in a highly accessible location. Then again, it does have a cultural landscape/outdoor art element that could not be realized in many urban locations.

David Rubenstein (Carlyle Group), high profile donations to Washington Monument and Washington Cathedral repair, Library of Congress, National Archives, etc.

Catherine Reynolds and her husband, mostly donations to national/nationally positioned organizations (Smithsonian, National Museum of Women and the Arts).

Betsy Casey (provided large grants to the Washington Opera and what is now called Casey Trees, dedicated to management and expansion of the city's urban forest).

The problem for DC is that most of the super rich want to give to the national institutions, not locally focused organizations and projects. By contrast, local business people who become rich often focus their philanthropy locally (e.g., "The Future Is Now: Behind the Surge In Los Angeles Arts Philanthropy," Inside Philanthropy).

Betsy Casey was an exception. This could change with the creation of a local fine arts museum and other high profile signature but local institutions.

There can be ethical and other issues associated with such donations ("Big Gifts, Big Problems: Takeaways From Capital," Inside Philanthropy). This is called "reputational risk" ("Defining Reputational Risk," Risk Management Monitor).

Foundations

Foundations

Grants for programs and facilities (capital) which don't have to be paid back.

Including directed fund accounts for the arts organized by Community Foundations

And large capital donations.

In DC, the Cafritz Foundation is a kind of real estate operating foundation that uses revenues on culture related projects. Otherwise, the DC area is weak on foundations compared to other cities, because it didn't have much of an industrial or business base, which is the source of wealth for many foundations (Ford--cars; Pew--oil; Abell--newspaper; Knight--newspapers; Kresge--retail; W.T. Grant--retail; Mellon--banking and other; Carnegie--steel; etc.).

This can blow up if a foundation has problematic affiliations ("Institutions Distance Themselves From Sackler Family Donations," NPR).

Program related investment (loans from foundations)

capital projects

Like revenue bonds issued by cities, program related investment by foundations is the equivalent of a loan. Because it's meant to be paid back, I don't think this can be seen as a huge panacea for arts organizations. Projects need to be successful for them to be able to pay back a loan. Many such projects, funded by either local governments or foundations, have failed in their ability to pay back such loans.

I've noted my reservation about PRI wrt the cultural plan already. But if it's put in the context of a long term, lower interest loan, options for full or partial forgiveness, and as a counterparty that is more willing to negotiate terms in tough times, etc., then I can live with it, as long as it's made very clear that it is a loan not a grant, but the nonprofit does receive an advantage in terms of lower interest and a willingness to renegotiate terms if it becomes necessary.

For example, had DC's City Museum been funded through loans ("PRI") from foundations instead of traditional loans, it might have survived.

Working capital loan programs by foundations

funds to address cash flow and other problems

This is a kind of support intended to help organizations deal with funding timing issues, prevent organizations from "going out of business,"etc. The intent is that the loans are paid back. Such loans from private sector sources would have exorbitant interest rates.

-- Arts & Culture Loan Fund, McArthur Foundation

-- Arts Loan Fund, Northern California Grantmakers

-- Financing, Nonprofit Finance Fund

Corporations

Corporate donations, grants and sponsorships

grants and capital projects

This works at a couple different scales, big corporations with a national or international footprint versus more locally based organizations. National corporations tend to fund national organizations (The Art of Winning Corporate Grants, Americans for the Arts). National organizations especially are doing it for them, not for you/out of civic interest, usually ("Corporate giving tied to branding, image," Arizona Republic).

They may fund specific programs, exhibits, donate to capital campaigns, etc.

Sponsorships are employed for events such as museum exhibits, free attendance days at museums, etc., and festivals, and if amounts received are greater than costs, the organization has some revenue left over that it can use for other activities.

Local arts groups in a city tend to get small grants from small firms, while big museums and cultural institutions get big dollar grants from large corporations doing brand development.

For example, national corporations like General Motors gave money to national museums like the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture. JPMorganChase supports arts organizations. Bank of America has an arrangement where its cardholders get one free admission each month admission to various museums because of its arts and culture philanthropic program.

Locally headquartered national corporations support institutions in their home community, like like FedEx in Memphis or Whirlpool in Benton Harbor, Michigan.

In fact as corporations consolidate or move this becomes a problem for local communities. For example, CSX moving from Norfolk hurts the nonprofit sector there ("Real damage from Norfolk Southern's departure may be to Hampton Roads Image," Norfolk Virginian-Pilot). Bank and department store consolidation has reduced philanthropy in many cities. One of the issues of the merger of Constellation Energy into Exelon was continued corporate giving in Baltimore ("Exelon donations in Maryland made as agreed," Baltimore Sun).

Just like with foundations, there can be reputational risk issues when it comes to corporate funding ("Handling the Ethical Dilemmas that Corporate Partners Can Bring to a Charity," Chronicle of Philanthropy; "The Koch brothers open their wallets for the arts. But should arts groups take Koch money?," Studio360, Public Radio International).

Decades ago when I worked for the Center for Science in the Public Interest, one of the initiatives was pointing out how alcohol, tobacco, and unhealthy food purveyors were big supporters of organizations in the Black and Hispanic communities.

Proffers associated with for profit real estate development

grants, space access, capital projects

In return for density bonuses and other "relief" from zoning and building regulations, property developers provide benefits in return, which can be monetary or in-kind, and either for operating funds or short term or long term access to space.

In our area, Arlington County, Virginia is one of the best at this. There was an article ("Mixed-Use Bethesda Development Plan Includes Movie Theater") in the Bethesda Magazine website this week about a project in Bethesda asking for a height bonus in return for a 4000 s.f. theater, although there were no details about specifics (rent: free or not; who would run it; etc.). E.g., my understanding about the arts retail at Monroe Street Market is that they were guaranteed low rent ($15/s.f.) for only 5 years.

In DC, I don't think the agreements are negotiated strongly enough to make the benefits clear and with the greatest possible return. My preference is for structural/permanent benefits with clear management systems, etc. (E.g., Howard Theatre, really really bad.) I don't think getting 1,500 s.f. at the Atlantic Plumbing Building for Washington Project for the Arts is a huge thing, even it is 1.5x the size of the ground floor of my house.

The Economic Function, Billboard text at the corner of Corporation Street & Alma Street, Sheffield S3. 6 April - 20 April 2004, By Hewitt and Jordan. The work 'The economic function of public art is to increase the value of private property' sets out to question the function of art in the public realm within the economic regeneration of post industrial cities.

These projects may end up being serious constrained and subsumed in relationship to the bigger real estate developments of which they are a part ("The $500m Shed: inside New York's quilted handbag on wheels;" "Studio 144: why has Southampton hidden its £30m culture palace behind a Nando's?," Guardian). From the article on the Hudson Yards project:

It seems fitting that the cultural centre of New York’s latest luxury private development should look like a quilted Chanel handbag. Rearing up at the northern end of the High Line on Manhattan’s reborn West Side, the Shed presents a 10-storey wrapping of puffed-up diamond cushions to passersby, standing as the gaudy gateway to Hudson Yards – the most expensive real estate project in US history. ...

All hope has been vested in the Shed as the one redeeming feature of Hudson Yards, a project roundly condemned as the ultimate fruition of disaster capitalism. Floating on a 28-acre magic carpet over the train tracks, it is a place where glistening towers of $30m apartments rise above a vast shopping mall of luxury brands – a millionaire’s playground that, by some estimates, has benefited from almost $6bn in public funding and tax breaks.

Within this bloated commercial citadel, the Shed has been billed as the one truly public element, standing on a slice of city-owned land and mostly funded by private philanthropy. Its director, Alex Poots, formerly of the Manchester international festival, said its publicness was the very thing that attracted him to move there. ...

The problem was it had to be squeezed into the profit-led plans of Related Companies and Oxford Properties Group, the developers of Hudson Yards, who deemed that a big moving shed would get in the way of people seeing their mall. So the site was shrunk, flipped 90 degrees into the back corner of the site, and plugged into the base of one of their luxury apartment towers, while the four shells were reduced to one. “It’s our deal with the devil,” Diller told me in 2017. “It allows us to get extra back-of-house space.”

Flickr photo by Lenny Spiro.

Community Reinvestment Funding from Banks

capital projects although separately banks often make financial contributions to arts and culture projects from other revenues

Federally chartered banks are required to invest in the communities in which they operate and this can include support for culture related capital projects among other programs such as affordable housing and community improvement. These loans and contributions have different terms and arrangements compared to traditional loan products.

-- The Community Reinvestment Act and the Creative Economy: Investing in Creative Places and Businesses as Part of Comprehensive Community Development, Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco

-- "With bank support arts organizations help build better communities," Minneapolis Federal Reserve Bank

Federal (and State/Local) Historic Preservation Tax Credits/New Markets Tax Credits/Conservation Easements

capital projects

These programs (and Opportunity Zones in the next category) are enabled by government legislation that creates tax credit and other programs that can generate funding streams for culture-related and other projects ("Historic tax credits critical to revitalization," Richmond Times-Dispatch). They are tricky to categorize because they are enabled by the government, funded by the private sector, and benefit nonprofits.

In DC, the Atlas Performing Arts Center used historic preservation tax credits to help pay for the $20+ million project. Many theater projects around the country use this funding resource. Some states and on occasion local governments, have parallel funding historic preservation tax credit programs also.

However, the recent changes in federal tax law make these programs harder to use and reduce demand for participation by corporations since their taxes are so much lower, they aren't motivated to seek further tax reductions.

Loans in Opportunity Zones

capital projects, or projects with a revenue stream of some sort

I've been meaning to write about this new Trump Administration program. It's a tax credit program for investors seeking to reduce their taxes. It can be a source of funding for projects in lower income geographic areas that qualify. But these are loans, not grants.

Traditional loans from traditional financial institutions

capital projects mostly but not exclusively

Didn't work out for the City Museum... The interest rates are usually at market rates. They have to be paid back. Lenders can take control of properties, etc. This is what happened to the failed attempt to create an Armenian Holocaust Museum. The "donor" to the project wasn't so much a donor as lender to the project to buy the buildings. When the project failed to proceed, the lender called the loans and got control of the buildings.

Real Estate Activation benefits

grants, dedicated space for culture programs, public art

The Vessel by Thomas Heatherwick Studios, Hudson Yards/The Shed, New York City. Photo by Elvert Barnes.

Arts and cultural spaces can be provided by property developers driven by the desire to increase marginal economic returns for the project overall. The principals might have an interest in arts and culture but they are doing this to make their developments more successful, worth more money, have more customers, charge higher rents, have lower vacancy rates etc.

The Vessel sculpture-stairway by Thomas Heathewick in Hudson Yards, New York City has attracted criticism as this photoshopped reinterpretation indicates. (Artist unknown.)

The culture program of The Shed at the just launched Hudson Yards development in New York City is an example. It's partly proffer, partly to make the project more successful.

Daniels Corporation in Toronto. They want the activation but as a corporation they seem to be committed to providing valuable cultural benefits ("Vibrant New Arts and Cultural Center Announced at Regent Park," ArtDaily).

Monroe Street Market in DC has a pedestrian street lined mostly by small studios/sales spaces for artists and craftspeople. In presentations Jim Abdo talked about how great this was, but he didn't acknowledge that filling out that space with traditional retail would have been really difficult.

THEARC (Town Hall Education and Recreation Center) in DC's Ward 7 was built in part to help revitalize an adjacent community, but also to help push the adjacent real estate development forward in an area that was hard to invest in on a strict profit basis ("On Mississippi Ave. SE, a place of light and learning," Washington Post). It's still a great community asset regardless of its genesis.

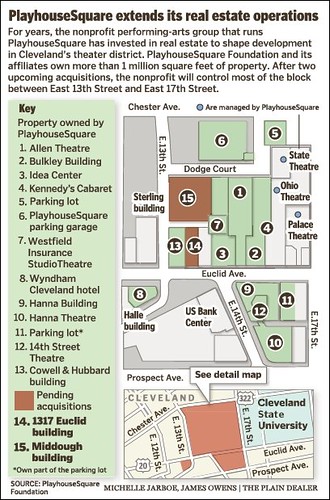

Real estate development and operation by nonprofit organizations

Cleveland Plain Dealer graphic.

Cleveland Plain Dealer graphic.Cultural districts that are systems integrators in terms of funding sources

Pittsburgh Cultural Trust; Playhouse Square Development Corporation, Cleveland; BAM (Brooklyn Academy of Music) Culture District; Upper Manhattan Empowerment Zone (they did a presentation c. 2003-2005 as part of the planning process for the U Street DUKE Plan -- back in the day OP did some great capacity building programming. On that panel were representatives from the KC district that has the Negro Leagues Baseball Museum, Greater Philadelphia Tourism Corporation, and Kathy Smith/Cultural Tourism DC).

In real estate finance they talk about the stack, which is comprised of multiple layers each which represents different types of funding.

Multifaceted cultural districts pull together all sorts of funding streams to fund capital projects and operations. It's not really a separate category because all the funding sources are listed, but they are masters at putting it together.

Property related revenue generation by cultural organizations

funds can be used for any purpose

By this I don't mean income from renting facilities or a bit of unused office space to other organizations, which is a normal income stream. I mean "big money."

It might mean one-time revenues from the sale of developable land or ongoing revenue from owned projects which the group may or may not manage.

E.g., Playhouse Square generates rental income from projects, including I think housing ("PlayhouseSquare stars in its own real estate revival," Cleveland Plain Dealer). From the article:

The nonprofit corporation also manages office buildings, industrial facilities, bank buildings and retail strips across the region and expects to grow through property acquisitions, a major theater redevelopment and an expansion into leasing and tenant representation.BAM too I think.

Today, roughly 30 percent of the foundation's revenue is tied to real estate. ... The nonprofit's model -- part performing-arts presenter, part economic-development engine -- has been mimicked by arts groups from New Jersey to London. ...

Real estate has provided the foundation with a way to subsidize arts and education programs and to create what Art Falco, the chief executive, refers to as a "working endowment" to ensure the nonprofit's survival.

"We're not aware of any other organization, particularly in the performing arts, that has taken this approach," Falco said. "It's just been an evolving strategy, as we have moved from renovations of the theaters to operations of the theaters to being a catalyst for neighborhood development."

While they don't devote the money to culture, George Washington University generates a significant amount of income from real estate development, office buildings proximate to their campus. So does Harvard, MIT, and Yale, among others. Although Ohio State University and University of Pennsylvania got into real estate development to help improve the area around their campus, to improve security, etc.

The site for a tall building overlooking Central Park is worth a lot more than the typical property that a cultural organization may be able to sell. 53W53, Manhattan.

The biggest examples that come to mind for me besides the Cleveland and Brooklyn are housing developments as part of museum campus developments, such as the apartments at the Newseum in DC, the Museum Tower next to MoMA in NYC ("Museum Tower's $70 million duplex the newest addition to NYC skyline," Bloomberg Businessweek).

There are projects with museums in Denver and Dallas, but they may or may not result in ongoing revenue streams for the arts institution. I think like with the MoMA project, they are one time revenue gains. MoMA got a $126 million payment from the developer.

DC does have the capacity for supra best practice: Sumner School redevelopment. One best practice one-off variant was done by DC Public Schools in the 1980s. A playground for an unused school in the Farragut North area--Sumner School--was leased for 99 years to a developer, who built an office building on the site, as well as incorporating part of an additional school, Magruder, into the office building. But as part of the lease, the developer agreed to renovate the Sumner School, and maintain it for the life of the lease, and that building is now used as the school system's museum and archives and for events.

So not only does the school system get lease payments on the office building, it got a renovated cultural facility that they don't have to pay to maintain.

But generally, this is tough to do and the typical nonprofit doesn't have expertise in real estate development.

Colleges and Universities

facilities access, capital projects, program operation

This is a special category. They don't provide funds to non-affiliated arts organizations. But many colleges and universities own and operate cultural facilities also open to the public, sometimes in unique ways. Many times, these initiatives are related to academic departments and programs. Mostly the facilities are on campus, but some are off campus, usually the result of the acquisition of cultural assets that had "been on the skids."

GWU and cultural events at its Lisner Auditorium is the most prominent example in DC. UMD and George Mason U have arts centers programmed for public audiences. Many universities have art museums or other types of museums. In DC, GWU has a history museum now and houses the Textile Museum as well. The Katzen Arts Center at AU is the closest thing DC has to a local arts museum.

Examples include public radio and television affiliates. In DC that includes WAMU-FM at American University and WHUT-TV, a public television station at Howard University. UDC used to have a radio station but when the city was broke, it sold off the station to CSPAN for the revenue. (Other agencies in other cities have sometimes done something similar.)

But WBUR, the NPR station owned by Boston University just opened a big facility with public functions, meeting rooms etc. WXPN/World Cafe in Philadelphia. Not sure on the business aspects of the music hall, but the radio station is affiliated with Penn.

Some universities have galleries off campus in the community, like the Massachusetts College of Liberal Arts Gallery 51 on Main Street in North Adams. Emerson College in Boston owns a number of theaters.

Gettysburg College owns a theater that is publicly programmed, located in the downtown of the city, which is decidedly "off campus."

MICA and John Hopkins University renovated the Parkway Theatre in Baltimore. It includes certain of their academic programs, space for the Maryland Film Festival and maybe other organizations, and the theatre space. The Peabody Conservatory unit of JHU offers concerts, etc.

Photo from the Right to the City exhibit at the Anacostia Community Museum.

At one time Catholic University (CUA) owned the Newton Theater on 12th Street in the adjacent Brookland neighborhood, but they sold it off and now it's a CVS.

Some colleges have moved their bookstores to adjacent areas off campus, including in DC, CUA.

Labels: arts-culture, capital planning and budgeting, municipal finance and budgeting, nonprofit funding, nonprofit management, public finance and spending, tax credit programs

9 Comments:

urgh, I forgot about % for arts, usually for space or public art, as part of construction projects, either as part of public projects (like transit or buildings) or private projects.

LA is thinking about redirecting this funding stream to pandemic related funding needs for arts groups.

https://www.latimes.com/entertainment-arts/story/2020-04-29/coronavirus-los-angeles-councilman-ryu-proposal-cultural-development-fees-for-arts-relief-fund

e.g., this is the program in LA:

https://culturela.org/percent-public-art/private-arts-development-fee-program-adf/

-----

https://nasaa-arts.org/nasaa_research/state-percent-art-programs/

On the federal level, since 1963 the General Services Administration has maintained the Art in Architecture Program, which allocates one-half of one percent of construction cost for art projects

https://www.artlawgallery.com/2012/10/articles/artists/public-art-programs-1-for-the-99-part-one/

Excellent discussion of green bonds in the context of Longwood Gardens, a public garden in suburban Philadelphia.

Although it doesn't emphasize the point that bonds have to be paid back.

Smaller nonprofits should be wary about bonds, because they're basically loans.

Longwood Gardens’ $250 million renovation taps increasingly popular ‘green’ bonds

https://www.inquirer.com/business/longwood-gardens-renovation-250-million-green-bonds-20220213.html

"oters in Jersey City Embrace a New Tax to Finance the Arts"

https://www.nytimes.com/2020/11/04/arts/jersey-city-arts-tax.html

... with a substantial majority of ballots counted, 64 percent of the voters there supported such a tax in a nonbinding referendum that is now expected to gain final approval from the City Council.

“It shows that the arts are important to people even in the toughest of times,” said Robinson Holloway, a former chair of the Jersey City Arts Council who helped develop the idea for the new tax.

For Jersey City, the vote is expected to produce a reliable, dedicated revenue stream that will not be affected by the vagaries of municipal budget negotiations, where arts funding is often an easy target.

For the wider arts community, there was a sense that Jersey City had employed a concept that might make sense outside its borders.

with a substantial majority of ballots counted, 64 percent of the voters there supported such a tax in a nonbinding referendum that is now expected to gain final approval from the City Council.

“It shows that the arts are important to people even in the toughest of times,” said Robinson Holloway, a former chair of the Jersey City Arts Council who helped develop the idea for the new tax.

For Jersey City, the vote is expected to produce a reliable, dedicated revenue stream that will not be affected by the vagaries of municipal budget negotiations, where arts funding is often an easy target.

For the wider arts community, there was a sense that Jersey City had employed a concept that might make sense outside its borders.

It's not very much.

The new tax is not a cure-all for local art organizations’ financial needs. At the half-a-penny rate, it is currently expected to generate between $1 million and $2 million a year, which will be distributed to select organizations or individuals whose applications will be vetted by a committee. But to arts leaders in Jersey City, the vote in favor of the tax is a victory for their central argument: that local arts and culture are economic drivers and assets that residents value enough to pay for.

ZooMuseum District, St. Louis City and County

https://mzdstl.org/taxrevenue/

Detroit Art Institute millage, Wayne, Oakland, and Macomb Counties

https://www.detroitnews.com/story/news/politics/2020/03/10/detroit-institute-arts-renewal-millage-election-results/4954684002/

Charlotte NC arts tax failed, 11/6/2019

https://www.charlotteobserver.com/entertainment/arts-culture/article237022269.html

Manchester arts venue Factory International renamed after Aviva

https://www.theguardian.com/uk-news/2023/jun/20/manchester-arts-venue-factory-international-renamed-after-aviva

Aviva is an insurance company.

One of the most eagerly anticipated new cultural venues in Europe is to be renamed after an insurance company in one of the UK’s biggest cultural corporate sponsorship deals.

The £210m flagship building in Manchester, previously called Factory International, will now be called Aviva Studios after the insurance giant Aviva acquired naming rights for, it is understood, £35m.

This article happens to be from Pittsburgh but is relevant generally, in how music organizations end up tailoring their offerings to what foundations are willing to fund. Making the point of the value of a more objective process.

https://newsinteractive.post-gazette.com/Pittsburgh-symphony-music-tickets-foundations-arts-funding-diversity/

6/19/2023

Leading from behind

To secure funding, Pittsburgh’s musical organizations dance to local foundations’ tunes

If everyone who attended that February concert paid the full $30 ticket price — the orchestra typically draws about 100-120 listeners per concert — the show would have pulled in about $3,600. That’s nowhere near enough to cover the cost of paying the composer and the roughly 40 musicians in the Chamber Orchestra.

And that’s one of the economic realities of the classical music industry: Most performing arts organizations don’t make enough money in ticket sales to pay the bills.

To make ends meet, these nonprofits are heavily subsidized by a combination of individual donations, state funding and philanthropic foundations.

“The scale of what we’re able to do in the end is really determined by whether we get funding,” said Andrew Swensen, the Chamber Orchestra’s part-time executive director.

King County enacting a sales tax comparable to ZAP, the same 0.1 of $10.

https://www.seattletimes.com/entertainment/king-county-oks-sales-tax-increase-for-transformative-cultural-funding

King County OKs sales tax increase for ‘transformative’ cultural funding

12/5/2023

King County’s arts and culture sector is getting a major boost. On Tuesday, the Metropolitan King County Council unanimously approved a new levy that will provide hundreds of millions in funding to arts, heritage, science and historical preservation nonprofits over the next seven years. Funded through a 0.1% sales tax increase, the new program — called “Doors Open” — is expected to distribute more than $100 million to hundreds of local nonprofit organizations each year.

Nearly two decades in the making and hailed as a game changer, the program and its steady stream of funds will be transformative for the sector, which is still feeling the impacts of the pandemic.

A wide swath of King County organizations — small and large, metropolitan and suburban, focusing on science, heritage or the arts — can receive funding, from groups like Friends of the Issaquah Salmon Hatchery to the Auburn Symphony Orchestra and the Seattle-based Northwest African American Museum.

The sales tax increase, a penny for every $10 spent, will go into effect in April and is estimated to bring in roughly $72 million in 2024. That revenue is expected to increase to about $100 million in 2025, the first full year of collections, and will increase each year with inflation. The program will be in place for seven years, after which it will have to be re-approved either by council vote or a public vote.

... Constantine’s new proposal, submitted to the council in late September, came after the April passage of statewide legislation that allowed counties and cities to create a cultural access program through a council or commission vote rather than a ballot measure. The proposal also responded to equity concerns raised by critics of the 2017 measure, carving out more allocations for organizations that serve vulnerable populations (including veterans, and people experiencing homelessness or mental illness) or are located outside of established cultural centers.

https://www.latimes.com/entertainment-arts/newsletter/2023-03-24/how-an-l-a-arts-coalition-founded-during-the-pandemic-is-strengthening-small-arts-groups-essential-arts-arts-culture

How a coalition founded during the pandemic is helping small L.A. art organizations thrive

Those informal sessions led to the establishment of the Los Angeles Visual Arts Coalition, known as LAVA, a network of almost three dozen small- to mid-sized arts organizations that rallied in support of one another at a time when institutions everywhere were grappling with remote work, social distancing and the bureaucratic mire of PPP loans. This included spaces such as Crenshaw Dairy Mart, Clockshop, the MAK Center, Los Angeles Contemporary Exhibitions, the Mistake Room and Self-Help Graphics.

One of their earliest initiatives was to create a shared system of fundraising. This allowed for strength in numbers. It also allowed small arts groups without well-greased fundraising apparatuses to benefit from the resources and knowledge of larger arts institutions.

Three years later, LAVA has reached a milestone: The group — which operates as a nonhierarchical coalition — announced this week that, thanks to catalyzing grants from the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation and the Teiger Foundation, it had raised $2,660,000 in support of its aims. Now LAVA is dispensing $50,000 in unrestricted grants to each organization within the group. Within the larger institutions in the coalition, such as the ICA LA, which has an operating budget of $3 million to $3.5 million per year, the funds will help support a range of budgetary needs. For the smaller organizations in the group, however, many of which operate on budgets of $1 million (or far less), the grants have the potential to be transformative.

It also allowed small nonprofits to share resources that would have otherwise been prohibitive. This includes professional development workshops that allow members to sharpen their fundraising abilities or refine their mission statements. “Individually, we can’t hire these consultants,” she says. “But we can bring them on all collectively.”

A Penny for Your Thoughts: How SCFD Tier I Institutions Use Their Funding

https://www.westword.com/arts-culture/how-colorado-scfd-tier-i-institutions-use-their-funding-25434827/

Post a Comment

<< Home