The problem when you define every outcome as a success, you don't learn, and therefore failure is more likely: bike share in Seattle and Los Angeles as examples

A few years ago at a private conference on bike sharing associated with the League of American Bicyclists annual meeting, I got frustrated by the presentation by the main presenters because they defined every example, even a two station bike sharing program in one of the Carolinas that had a handful of users per week, as a great success, making the point that the definition of success can be very dynamic.

I countered: when you define everything as a success, you don't ever learn, you don't figure out what works well and what doesn't. (While they weren't happy with that statement, a person from LA MTA commented I had good insights...)

When planning for Seattle's bike share (user pictured at left) was going on, they used DC as an example of why they would be successful, but were not clear at all about the fact that 97% of revenue that makes DC's system break even on an operating basis is generated by tourists who either don't care or haven't figured out how to use the system without racking up additional fees.

Not to mention that compared to other major bike sharing systems, the membership for the Capital Bikeshare program grows at a much slower rate.

Besides the fact that Seattle has nowhere near the same level of tourism, Seattle has a mandatory bike helmet law, which makes itinerant bike use much less convenient (bike helmet use requirements in Melbourne are believed to be a major reason why that system isn't successful, "Spoke too soon: Melbourne Bike Share to drag chain another year" and "Bike Share Scheme Melbourne Usage Statistics | Helmet Law." Melbourne Age).

For these and other reasons the system is on the verge of financial failure ("Seattle's Pronto bike-share nonprofit teetering, seeks $1.4M rescue by city" and "Bike share's failure deflates Seattle's self-image," Seattle Times) and the city is going to take it over. From the second article:

The news that Seattle’s bike share program is insolvent only a year after opening is, symbolically anyway, a wound to Seattle’s green psyche.A couple of other articles on bike share such as "How NYC's bike share saved itself," Fast Company, get into more detail about the extent to which programs must go in order to operate better.

It could be due to mismanagement. Or a lame rollout. These were some of the reasons offered for how a bicycling program could falter so badly in a place that fancies itself as Bike City, USA. ... there’s a more vexing problem: Nobody’s riding the bikes.

In its first year, people took 142,832 rides on Pronto bikes. That’s only 391 rides per day. It’s about seven rides taken at each station per day. Each station brought in only an average $30 a day in revenue.

Were advocates, planners under the gun from their political masters, and consultants from bike planning firms not so focused on defining everything as successful, likely there would be more real success.

FWIW, I don't think many cities in North America are capable of being successful with bike share, if success as defined as lots of users, high daily usage, greater take up of bicycling for transportation, low subsidies, etc.

Bike share in DC. Wikipedia photo.

That being said, it might be worth supporting bike share applications in more limited circumstances, and not necessarily for transportation, such as for recreation and health reasons.

Many bike advocates counter that most forms of mobility "are subsidized" so why shouldn't bike share be subsidized, just like roads, driving, and transit?

But that begs the question that should be asked, but isn't:

what is the best way to promote greater adoption of bicycling for transportation, at what cost, and is bike share the best choice (by doing a cost-benefit analysis) and program on which to spend scarce resources?Spain's Biceberg is an underground bike parking system that can store 23, 46, 69, or 92 bikes, accessed through an above-ground kiosk. I think these should be installed in apartment-dominated neighborhoods in the core of DC, such as Columbia Heights or Dupont Circle, at transit stations, parks, and other public facilities to increase the availability of secure bicycle parking.

Giving people bikes, building bike parking including high capacity parking in neighborhoods dominated by multiunit housing without the capacity for on-site bike parking, requiring multiunit residential buildings and office buildings to provide high quality bike parking, creating wide ranging transportation demand management programs sponsoring biking, providing loan/payroll deduction systems for bike purchases (Bicycle Loan Program | VACU - Virginia Credit Union; Tax free bikes for work through the Government's Green Transport Plan, UK) are probably ways that would reap more cost effective results.

Unlocked Capital Bikeshare bikes, 3rd and Pennsylvania Avenue SE.

Unlocked Capital Bikeshare bikes, 3rd and Pennsylvania Avenue SE.But as along as elected officials cycle through Washington DC or NYC and see bike share in operation, they are going to demand that their city deploy a bike sharing system of their own, without recognizing or acknowledging that highly visible cool bikes don't in and of themselves make a successful program.

Los Angeles. It happens that after I started writing this piece, I did come across an op-ed ("L.A.'s bike-share program is being set up to fail") in the Los Angeles Times that makes some of these same points, although the piece has a serious error (attributing the better financial results of some programs solely to the sales of advertising or sponsorships).

The article makes three major points:

1. While bike share is touted as helping to reduce car use, most users shift from public transit;

2. The new bike share system sponsored by the transit agency will be incompatible with the other systems being deployed in cities like Long Beach and Santa Monica

3. Since the system is most likely to be used by transit users, and most transit users in LA County are low income, the price to use bike share is too high to be used by low income users.

Creating a critical mass of infrastructure that supports sustainable mobility. Note that the author argues that Downtown LA is the place where bike share is most likely to be successful, but states that this area is already served by a dense network of transit, making bike share unnecessary, that when most transit users are making longer trips, they aren't likely to end up using bike share.

Mobility shed diagram: think of the rings as representing different mobility modes (shuttle, bus, subway, biking, walking, etc.), and varying in width based on the amount of distance that can be covered in five minute increments.

Mobility shed diagram: think of the rings as representing different mobility modes (shuttle, bus, subway, biking, walking, etc.), and varying in width based on the amount of distance that can be covered in five minute increments. The mobility shed. In order for this scenario to work, there need to be tight links between transportation and land use planning, a great deal of density, and short distances between residential areas and primary destinations--activity centers such as major centers of employment like DC's Downtown, community business districts and supermarkets, entertainment destinations (stadiums, arenas, auditoriums, parks), etc.

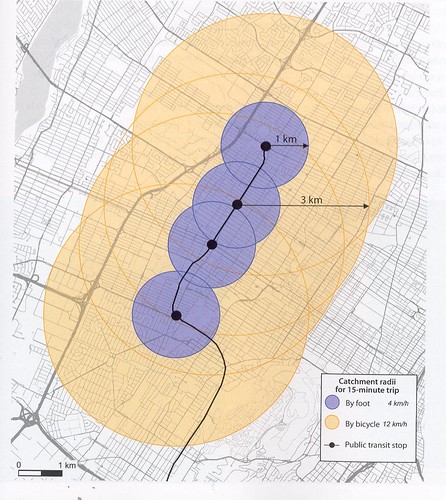

Bike and walk sheds from transit stations. From Planning and Design for Pedestrians and Cyclists: A Technical Guide, produced and published by VeloQuebec.

Bike and walk sheds from transit stations. From Planning and Design for Pedestrians and Cyclists: A Technical Guide, produced and published by VeloQuebec.Given that a bike ride of three miles takes about 15 minutes, this presupposes a fair amount of density within a three-mile radius.

Cities such as NYC, the core of Washington, the core of Chicago, San Francisco, etc. qualify, while most others do not. Salt Lake City might be an exception for supporting a working system because the block size there is so big--an average city block in SLC is four to five times larger than blocks in other cities.

Cities like San Francisco with severe topography present a special case also.

Why bike sharing systems fail. Not having this set of land use and transportation conditions is why bike sharing deployments in cities like Palo Alto failed, even though it was part of a regional bike sharing program, anchored by San Francisco, and why cities like Chattanooga ("2 years later, Chattanooga bike-share program is struggling," Chattanooga Times-Free Press), San Antonio ("San Antonio Bike-Share Threatens to Close Without Major Sponsor, Next City), and San Diego ("San Diego bike-share program hits snags over modest use," Los Angeles Times), and Toronto ("Clock is ticking for Toronto Bixi bike-share program," Toronto Star), among others haven't achieved much success with bike sharing. (Note that in Toronto, the system is being taken over by the Toronto Parking Authority and the regional transportation agency, and some of the problems are being addressed.)

Maps at Seattle bike share stations show the respective distances that can be covered by a five minute walk or a five minute bike ride. Image from Geekwire.

In the past, I've called this the mobility shed ("Updating the mobilityshed / mobility shed concept") and the maps for Seattle's bike sharing system are the first to illustrate the difference between "walk shed" and "bike shed" on posted maps.

In this scenario, bike share is complemented by walking, bicycling on owned-bikes, public transit (shuttle, bus, maybe streetcar, maybe light rail, heavy rail, railroad), one-way and two-way car share, taxi services, car rentals, even rollerblading and skateboarding, and electric bikes, mopeds, etc.

Car sharing is an element of a sustainable mobility infrastructure platform. Right: a Car2Go one-way car sharing vehicle in Washington, DC.

Members of car sharing systems like Car2Go and Zipcar can use sister programs in other cities across the US and Canada (for both systems) and Europe (for Zipcar).

The thing about bikes vs. bike share is that in most places the density of stations isn't likely to be great enough to be convenient for most trips, given that the normal advantage biking presents is the ability to perform your trip with complete efficiency, by being able to leave immediately from your origin point on bike and to arrive within a few feet of your final destination. That's why an owned bike typically makes more sense for people who travel primarily by bike.

However, offloading storage and security issues--especially in cities like New York--can make bike share a worthwhile alternative for many.

Lack of one regional system. It's hard to disagree with this kind of criticism. I agree that one common system is the best way to go at the metropolitan scale, but because it can take such a long time to launch, some communities get frustrated and go off on their own.

From the standpoint of mobility as a platform, it is counter-productive because it requires users to join or pay to use multiple systems. For similar reasons, it's why most metropolitan areas have combined transit fare media systems for local transit (although typically these systems do not include railroad services).

Launch of Citibikes in Jersey City. Jersey Journal photo.

This comes up in Hudson County, New Jersey, on the west bank of the Hudson River across from Manhattan, where Jersey City has decided to join into the Citibikes system ("Fulop: Citi Bike Jersey City launch 'one of the most exciting things," Jersey Journalr), figuring that most of their residents and/or employers are tied into NYC in terms of their work and living choices, so therefore their transit shed is anchored by and within New York City.

But neighboring cities like Hoboken are going with their own system ("Hoboken launches bike share program" Jersey Journal ) which won't be tied into the same system in NYC, but is much cheaper to launch and operate.

Launch of Next Ride in Hoboken. Jersey Journal photo.

That being said the Hudson Bike Share program has some interesting innovations in signage, outreach, communications, and in their creation of "no fee regional zones" where bikes can be retuned in locations outside of Hoboken.

I am not sure if some of these locations are in NYC, where the operator is based, with various bike rental locations in Manhattan. But this is interesting in how it allows cross-trips between certain locations outside of the normal "home zone" of the system.

The idea of the "no free regional zones" can be a way to deal with areas that don't participate (this is an issue with some boroughs in Montreal) or where there are a variety of different systems.

It's also an issue in Maryland, vis-v-vis suburban counties (Montgomery is part of the Capital Bikeshare system, while communities in and Prince George's County has considered developing a separate program) and Baltimore and Annapolis, which have some cross-trips with the DC metropolitan area.

It's also why the attempt by the US House of Representatives to create their own bike sharing system failed, when they should have just joined the DC bike sharing system. Sadly the failure of that closed system is used by Republican Congressmembers as a reason to denigrate bike sharing more generally.

Another issue concerning how "metropolitan" scale bike share systems are operated. One problem with bike sharing systems that isn't understood by users has to do with the fact that unless the system is run by a transit agency or only operates within a single jurisdiction, despite being branded as a single, metropolitan-scale system, it's actually organized on a jurisdiction specific basis. In reality it's a collection of separate programs unified under a single brand.

For example, in the DC area, the Montgomery County participation is financed separately from DC, as are the programs in Alexandria and Arlington County in Virginia). What this means is that revenues are collected by jurisdiction and not shared across jurisdictions, so there isn't the opportunity for cross-subsidies between high-use and low-use areas. This was an issue in San Francisco and is in Boston, with the Hubway system.

But not understanding this element may blindside smaller jurisdictions elsewhere, believing that the revenues generated by the "success" of the system is DC are shared with the other members of the "compact."

See these past blog entries for a discussion on bike planning and equity and increasing bike take up amongst low income populations:

-- "Equity as the sixth "E" in bike and pedestrian planning"

-- "Revisiting bicycle (and pedestrian) planning and the 6th 'E': equity and the City of Minneapolis Bicycle Master Plan"

-- "Urg: bad studies don't push the discourse or policy forward"

Frankly, saving time was the primary reason I started biking for transportation in 1990--I figured it saved me a minimum of 30 minutes each day compared to walking and/or using transit.

The problem is that transit agencies haven't been conceptualized as "transportation solution providers" as much as they are providers of bus or rail transit service. If they were, then agencies would integrate bike share into transit service operations very tightly. (This kind of thinking is why the German rail system has offered bike share for more than a decade.)

And to be fair, many transit agencies see the value of bike share in terms of providing a faster means to get from a transit station or stop to the intended destination, which may still be some distance away.

Boston's success with making equity a priority in bike share. But this issue is addressable. Boston has gone the farthest in creating programs making bike share widely accessible to low income populations, offering annual membership, including a helmet, for only $5, to people who qualify. (I have also suggested to public housing organizations that they integrate bike share and high quality secure bike parking on site but I haven't had much headway.)

Generally, this requires the involvement of agencies other than the local transit agency. In the case of Boston, it includes the city's transportation department and the city's the public health agency, and private funders. The local transit agency is not involved.

The Philadelphia Experiment. Note that the Philadelphia Inquirer has run a number of articles ("Why low-income people bike share less," Indego popular for university commuters and joyriders, mixed results for low-income outreach," "Ridership with reach," and "Indego has inroads yet to make") about the relative dearth of low income users of the Indego bike sharing system there.

Unlike say articles by the Washington Post on the streetcar project, which in my observation are more focused on painting streetcar use as moronic, the Inquirer articles explore the issue in depth. Mostly the system hasn't done very good marketing, and unlike Boston, they didn't create a discounted membership program for low-income uses.

But despite the existence of the Better Bike Share Partnership research initiative, of which the City of Philadelphia is a member, the Indego program doesn't appear to have launched with the implementation of best practices concerning take up by low-income populations, figuring that installing stations in low income neighborhoods was enough. DC's system has the same problem ("Who uses Capital Bikeshare?," Washington Post).

The CicLAvia "Open Streets" event in Los Angeles County is probably the most successful example of such a program in North America. Each event brings out 100,000 to 200,000 participants. The Los Angeles Metropolitan Transportation Authority is the primary sponsor of the event. Photo from the LA Times.

The CicLAvia "Open Streets" event in Los Angeles County is probably the most successful example of such a program in North America. Each event brings out 100,000 to 200,000 participants. The Los Angeles Metropolitan Transportation Authority is the primary sponsor of the event. Photo from the LA Times.By contrast the LAT op-ed suggests discounting transit service for trips that don't lend themselves to bike share. I think that's misguided.

While I do believe that fares and passes should be discounted for low income riders, the money to cover that cost needs to be appropriated separately from funds allocated to transit systems for general operations and capital improvement.

Otherwise, discounting fares merely reduce the revenue for the transit system, and the fare structure for transit in LA County is among the cheapest in the US already--bus costs about the same as DC (which is the about the cheapest in the US for major transit agencies) but riding heavy or light rail is the same fare, $1.75, although transfers between modes are free only with a weekly or monthly fare pass.

Conclusion. There are best practice analyses of bike sharing such as the Bike Sharing Planning Guide by the Institute for Transportation and Development, , and various studies by academics and other organizations (many are listed in this blog entry, "Bikeshare systems: Recent research on their growth, users’ demographics and their health and societal impacts," from Journalist Resource).

So it's not like there isn't good information out there about what works, what doesn't work, and what could work better.

Maybe the real issue is not that there isn't information, but that information is either not being accessed to begin with or it's not being used or it's rejected for non-evidence-based reasons.

Labels: bicycle and pedestrian planning, bikesharing, change-innovation-transformation, collaborative consumption, sustainable land use and resource planning, sustainable transportation, transportation planning

5 Comments:

I used Seattle, and yes the helmet law is a drag. The topography doesn't help that much either.

Suzanne lived there for many years, and has friends and some relatives there still.

We were there in 2008, and she was driving us to meet a friend and we were on some hill, in a car, that scared the hell out of me.

The other element is that distances between neighborhoods, e.g., Ballard to Downtown, Fremont to Downtown, West Seattle to Downtown, U Village to Downtown, etc., are pretty long.

E.g., it's 6.5 miles from Ballard to Downtown.

http://www.latimes.com/local/lanow/la-me-ln-los-angeles-bike-share-ridership-20160919-snap-story.html

Divvy system barely makes money from operations, mostly from sponsorships.

By expanding to low income areas, system generates significant revenue losses:

http://www.chicagotribune.com/news/local/breaking/ct-met-divvy-income-drop-20171226-story.html

Baltimore drops traditional bike share, switching to dockless, with heavy requirements to have dockless bikes and e-scooters in low income neighborhoods.

https://www.bizjournals.com/baltimore/news/2018/08/15/baltimore-terminates-current-bike-share-program.html

8/15/2018

Post a Comment

<< Home