Melbourne gets it, DC not so much...

In line with the "generational" arguments about smart growth vs. the shrinking city, car culture and automobility vs. walking and biking, the role of public transit, appropriate models for land use, compact development, and transportation in the city (vs. the way these concerns are handled in the suburbs), I have been engaged in a running debate about sustainable transportation in themail, which is a twice/week e-newsletter on good government. Two issues ago, my position was termed one of a zealot.

The article is short and worth reading and quoting in its entirety, but that violates fair use, so here is an excerpt:

THE future prosperity of Melbourne depends on the capacity of the public transport system to deliver increasing numbers of workers and customers to the city. The system can be a source of lifeblood to the city and to its property values; or it can be allowed to become a garrotte.

For 50 years, freeway advocates have argued that public transport is a social service for those too old, too young, or too incompetent to drive a car, paid for by taxing car-driving workers; and their arguments were heard. Public transport was starved of investment and maintenance was neglected. Melbourne's last great public transport project, the City Loop, was never quite completed. Ballarat, Geelong and Bendigo lost tram networks; much of regional Victoria lost its passenger trains.

Twenty years ago, public transport acquired a green tinge: tram and train passengers use far less energy per kilometre than car drivers and so, environmentally aware politicians began cautiously investing in improved rolling stock and better maintenance. But there were no big-ticket items.

The most compelling reason for investing in public transport isn't the environment; it is money.

Property only has value because people want to use it; and they can't use it if they, their customers or their workers can't get to it. Once investors own urban land, they build on it to recover their costs and earn a profit. As they earn a profit, values rise and more investors move in; old buildings give way to new and the process continues.

If workers and customers can't get to a city, values stop rising; old buildings are allowed to decay and soon values start falling.

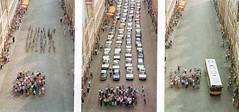

The geometry of city access is fairly simple: a four-metre reservation can carry about 1800 people an hour in one direction by bus or car; about 6000 people an hour by tram or light rail; and 20,000 or more people an hour by heavy rail. Once there, a worker or customer needs about 10 square metres of floor space while a car needs 36 metres of parking space.

[Note: in the U.S. we use different numbers. About 1800 to 2400 people by car, 6,000+ by standard bus, 10,000+ by bus rapid transit or streetcar, 15,000 to 25,000 people by light rail, and 20,000 to 40,000 people (in the DC region, in other systems with more than 2 tracks, the capacity is higher).]

An all-car city with ground-level car parking would be limited to about 180,000 square metres of usable floor space; if all parking was in multilevel car parks, this would rise to about 1.5 million square metres; while if most peak-time travel was by fixed-rail public transport a city could support at least 8.5 million square metres. This can be increased almost without limit by raising average building heights./div>

Urbanophile reprinted a blog entry Replay: “They’re Not Current” which starts out with this:

As part of keeping up with this blog, I read a lot of what other people write about various Midwestern cities. A recurring theme from Midwest urbanists is a frustration with local civic leaders’ unwillingness to implement what they see as new and better policies and approaches, especially in light of the struggles the region has encountered and the resulting imperative for change. This is often phrased in less than charitable terms and there seems to be a low opinion of community leadership in many places. I’m guilty of it myself at times. Sometimes it is warranted.

But other times a better way of looking at it was put forth by a friend of mine when he said of the people who he was working with on a civic project, “They’re not current.” By that he meant that while they were well-intentioned, smart, good at business, good at their technical specialty, and excellent at things like fund raising and building community support for initiatives, they simply weren’t up on the latest and greatest thinking in the urbanism space. They weren’t bad leaders or bad people at all – they just had gaps in their knowledge and thinking about cities.

That's how I feel about these arguments. Most people are not keeping up. Most people generalize from the automobility-based experiences to the city, not recognizing that the center city requires different policies and responses, and as our "AMerican Way of Life" has recentered away from community and more toward the nuclear family and an automobile-connected way of life, people have become cloistered and disconnected.

But hesitating really matters.

As communities in the DC region outside of the center city focus on intensifying development--Alexandria (King Street Metro area, Potomac Yards), Arlington (Wilson Blvd. corridor, Rosslyn, Crystal City), Fairfax County (Tysons Corner), Montgomery County (see the White Flint proposal as well as the revitalization of Bethesda and Silver Spring, and the next iteration of plans for Wheaton), and talk of building more densely at subway stations in Prince George's County, DC can't afford to remain static, even though for the most part, that's what it seems like the more traditional civic organizations want.

(Top image. Extract from a billboard during the Depression. The full frame of the image shows people lined up getting food at a soup kitchen. Bottom image: parking lots in Downtown Houston.)

Labels: economic development, sustainable land use and resource planning, transportation planning, urban design/placemaking, urban revitalization, urban vs. suburban

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home