How I would approach organizing the DC master transportation planning process and plan

For a couple years running, I'd produce an annual "transportation wish list," but frankly it was more like a master transportation plan. See for example, "The revised revised People's Transportation Plan/2008 Transit-Transportation wish list" from 2008.

For a couple years running, I'd produce an annual "transportation wish list," but frankly it was more like a master transportation plan. See for example, "The revised revised People's Transportation Plan/2008 Transit-Transportation wish list" from 2008.As it relates to buses, "Making bus service sexy and more equitable" from last September represents my most complete thinking on bus planning and operations.

And this entry, "A "maintenance of way" agenda for the walking and transit city," is important in how it argues that if the city truly aims to be focused on sustainable transportation, then it needs to make all of its transportation operations practices congruent with the policy.

(Actually, these three pieces cover a lot of ground. Ideally all of that would be included in a transportation plan, plus my writings on bike and pedestrian planning, transportation demand management, etc.)

The point of those writings was to focus on the creation of a transportation system that optimizes livability and efficiency for DC residents, and supports the local economy. That includes serving the city's place as one of the metropolitan area's largest activity centers, especially at the core of the city, and the federal presence there, but with the intent of reducing automobile use.

In my opinion, DC still doesn't focus on transportation as a competitive advantage in the same manner as Arlington County or Portland, Oregon.

Those communities are known nationally for their focus on transportation demand management and/or transit expansion.

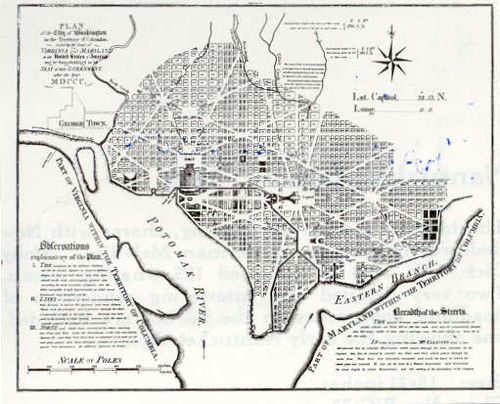

But because DC was "blessed" with a sustainable mobility-centric urban design by L'Enfant, DC is very successful with sustainable mobility--walking, biking, transit, car sharing--and a car light lifestyle.

As a result, while Portland and Arlington County get all the accolades for being so great at sustainable transportation, in fact DC kicks their asses as DC has more than 51% of commuting trips by residents being conducted by sustainable modes, and this is about 100% better than Portland and 50% better than Arlington. (Note that this statement is based on numbers that are a little old.)

I'd argue that to be innovative, the framework of the plan likely should be broader and more innovative than I expect it will be.

1. Guiding Goal #1: Creating a linked transportation and land use planning paradigm. In 2007 I wrote a paper for a class on how to create a truly linked land use and transportation planning paradigm for DC proper.

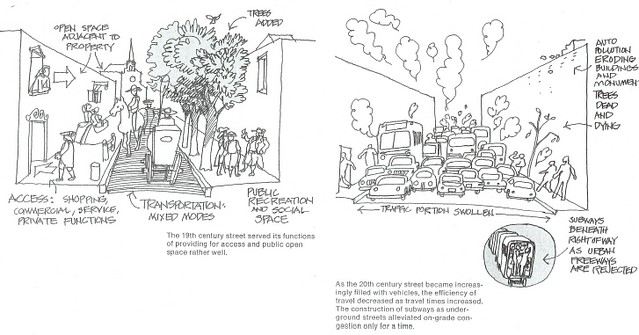

19th Century vs. 20th Century Street Design from the Central Washington Transportation and Civic Design Study (1977).

The framework was discussed in this entry, "Not being able to build your way out of congestion." It's based in part on San Francisco's Transit First policy which is enshrined in the City Charter and on the linked land use and transportation supply planning process in Utrecht, Netherlands ("Utrecht: ABC Planning as a planning instrument in urban planning policy").

And I would argue that counter-factual and counter-intuitive thinking needs to be embraced in this discussion. In other words, automobility proponents need to understand that their self-interest is actually served by sustainable transportation prioritization.

2. Guiding Goal #2: Social equity in mobility. The "Transit City" planning initiative in Toronto (since junked by the current mayor) makes the point that to be a transit city, the transit system must continue to grow, and that social equity should be a foundational element of transit planning.

From the article, "Toronto Plan rolls out new era in Transit," from the Toronto Star:

"Transit City is based on the principle that no one should be disadvantaged by not owning a car. (It) takes the high-quality transit service available in the core and begins to extend that to the four corners of Toronto," said TTC chair Adam Giambrone.

This goes for both planning and operations. Also see the report, Implementing Equitable Transit Communities Report, from the Puget Sound Regional Council.

It should also shape policy on fares and income support. Rather than "keep fares low"--although at this point, WMATA subway fares are now "too high"--I'd rather provide different kinds of supports to people who need them, such as how the SF MUNI system offers a "Lifeline" discounted fare card--for about 1/2 the cost of the normal monthly pass--for low income residents. (MUNI also allows youths to ride the system for free. They also provide discounted rates for seniors, as do most transit systems.)

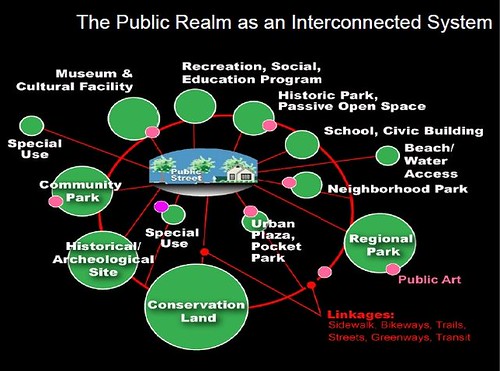

3. Guiding Goal #3: Placemaking, Complete Places and Urban Design should shape the quality of transportation infrastructure. DC's Comp Plan's Urban Design Element is a good start. Quality of place and what the Project for Public Places calls "placemaking" (diagram, right) needs to be a key element of the plan.

3. Guiding Goal #3: Placemaking, Complete Places and Urban Design should shape the quality of transportation infrastructure. DC's Comp Plan's Urban Design Element is a good start. Quality of place and what the Project for Public Places calls "placemaking" (diagram, right) needs to be a key element of the plan. Similarly, David Barth's concepts of the integrated public realm framework (diagram in the first paragraph above) and streets as linear parks complement this ideal. See "Complete Places are more than Complete Streets" and Public Squares and DC."

One element of this would be to create a "Chief Thoroughfare Architect," to focus on the placemaking characteristics of the roadway network, comparable to how transportation departments have a "Chief Engineer" typically in charge of traffic engineering, the position being one of the most important in the department.

Note that a "Chief Thoroughfare Architect" should probably have been trained as a landscape architect (and/or an urban designer).

4. Guiding Goal #4: transportation efficiency and optimality should be prioritized over maximizing choice. I get pretty worked up about this. Many people argue that the advantage of supporting sustainable mobility is that it gives people more choices. The problem with this argument is that just because individuals have more choices doesn't mean that they make the right choice or the right choice for the system as opposed to themselves.

See "More on *o* d*m* parking, parking, parking" and "Sustainable transportation is not about expanding choice, but about optimality, and how to design it into the land use and transportation system.

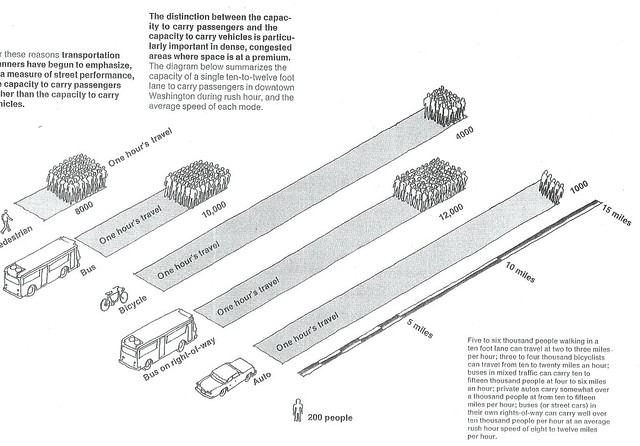

Part of this discussion should be a section on what I think of as transportation physics, or the physical, social, and economic aspects of space. Arlington's plan terms this in terms of moving more people with less traffic.

Mobility efficiency or the capacity of one traffic lane for various modes, from the Central Washington Transportation and Civic Design Study, 1977.

Related to this is prioritizing accessibility rather than motor vehicle throughput.

accessibility: the ability to reach destinations (by various modes) [1]

mobility: the ability of people to move on the network [1]

travel time: how long it will take to get from origin to destination with each of the travel modes [1]

land use: the distribution of activities [1]

activity centers: dominant employment centers, but can also be other major destinations such as schools and regional shopping districts. In the DC metropolitan area, sizes vary (primary, secondary, tertiary) with a minimum of about 25,000 in daily population and up to many hundreds of thousands of people. [2]

commuter shed: the area in which workers are employed and travel within to get from home to work

transit shed: the area served by the transit network [3]

mobility shed: the catchment area served by a transit station or key node in the network [3]

[1] - Accessibility Matrix, University of Minnesota Access to Destinations Study

[2] - Strengthening Transportation of Urban -- and Suburban -- Activity Centers and Activity Centers Briefing Book, MWCOG

[3] - Updating the mobilityshed/mobility shed concept

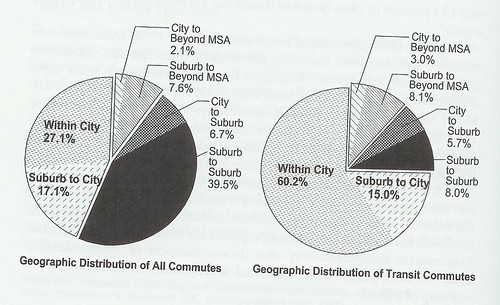

5. Guiding Goal #5: The city must balance intra-city transit needs for residents with regional mobility goals and maintenance of the city's central business district as a primary location for commerce (activity center) at the metropolitan scale. (Right: graphic on geographic distribution of commuting from Census Data. From Cities in Full by Steve Belmont.)

5. Guiding Goal #5: The city must balance intra-city transit needs for residents with regional mobility goals and maintenance of the city's central business district as a primary location for commerce (activity center) at the metropolitan scale. (Right: graphic on geographic distribution of commuting from Census Data. From Cities in Full by Steve Belmont.)For some guidance on intra-city transit planning, see "Making the case for intra-city (vs. inter-city) transit planning." And for planning transit at the metropolitan scale, see "Metropolitan Mass Transit Planning: Towards a Hierarchical and Conceptual Framework." (It needs to be updated.) Key are the concepts of monocentric vs. polycentric transit systems (see the discussion in Belmont's Cities in Full).

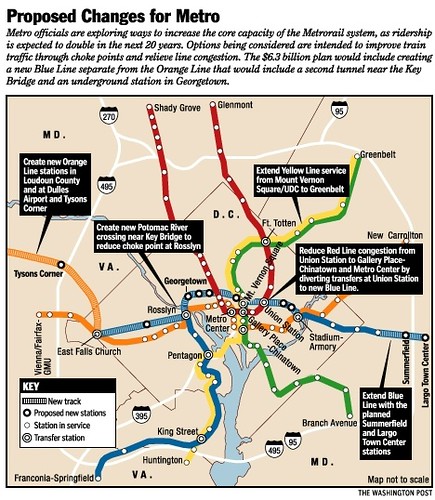

My writing on the necessity of the separated blue line for DC as a way to expand capacity at the core while also extending the reach of the transit system and providing more service to Union Station, the station with the largest daily ridership, is an example of transit infrastructure designed to accomplish both types of objectives simultaneously.

6. Transportation Demand Management including the creation of "Transportation Management Districts" needs to be embraced in a much more comprehensive and integrated fashion far beyond current practice.

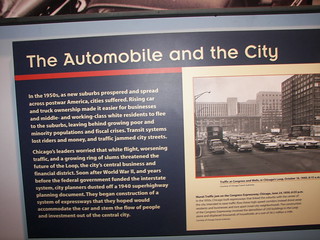

7. A discussion of local transportation history should be a plan element. I think that all transportation plans ought to include a section on local transportation history, not unlike the discussion of local transportation in the late 1800s and early 1900s in the America on the Move exhibit at the National Museum of American History. (The only time I've ever seen a comparable section on history in the Baltimore master land use plan, and it didn't cover transportation.)

I frequently cite the work of Peter Muller (“Transportation and urban form: Stages in the spatial evolution of the American metropolis”) which is based in part on J.S. Adams ("Residential structure of Midwestern cities"), and is maybe more accessible at this webpage, The Automobile Shapes The City: From “Walking Cities” to “Automobile Cities.”

I frequently cite the work of Peter Muller (“Transportation and urban form: Stages in the spatial evolution of the American metropolis”) which is based in part on J.S. Adams ("Residential structure of Midwestern cities"), and is maybe more accessible at this webpage, The Automobile Shapes The City: From “Walking Cities” to “Automobile Cities.”If you don't understand the history of transportation as it relates to the locality, you don't understand the foundations, shape, and possibilities within your local transportation system.

8. Innovative financing options should be outlined and explored in the transportation finance plan element. Models include the transit withholding tax in Oregon, transportation financing districts, Seattle's Bridging the Gap program (bond funding + general funds), and other value capture methods.

London, Stockholm, and Singapore offers the example of congestion zone charging. Note that I think that congestion charging isn't a viable direction for DC. Most of the metropolitan area's worst congestion is outside of the city, and other jurisdictions would use a congestion zone charge in DC as a recruiting tool to encourage businesses to relocate outside of DC proper.

This section of a master transportation plan should also discuss the reality of transportation financing and how gas taxes and registration fees don't cover the majority of costs for building and maintaining the roadway system. See the Brookings Institution report by Martin Wachs, Improving Efficiency and Equity in Transportation Finance.

9. DC should probably create a Transportation Commission to oversee and coordinate and prioritize transportation planning. The Zoning Commission and the Board of Zoning Adjustment do consider transportation issues to some extent, although the Zoning Code is pretty weak in terms of broader transportation requirements. DC doesn't have a Planning Commission.

While I think we should have a Planning Commission which incorporates Transportation responsibilities, since that's not likely to happen any time soon, I recommend the creation of an overarching Transportation Commission. (Right now the city has a Pedestrian Advisory Committee and a Bicycle Advisory Committee, and a "Circulator" Advisory Committee has been proposed.) Tempe Arizona and Arlington County come to mind as jurisdictions with best practice Transportation Commissions which could serve as an example.

This should be discussed in the plan.

10. Drilling the plan down by creating sustainable mobility elements within sector and neighborhood plans. So yes, DC doesn't do sector or neighborhood plans, although you can argue that Area Elements in the Comp Plan are a type of sector plan (although much less detailed than comparable plans in Arlington or Montgomery Counties).

In the Western Baltimore County Pedestrian and Bicycle Access Plan, one of the recommendations I made was that "sustainable transportation elements" should be added to the community plan process, which they adopted.

Similarly, I argue that the next generation of bicycle and pedestrian planning should be providing district/sector/neighborhood plans, including programming designed to assist people in transitioning to the adoption of more sustainable modes.

DDOT has some area transportation plans and "performance parking districts" but I would argue that there isn't a robust planning paradigm that guides these initiatives. Instead, achievements are variable, dependent on the quality of the personnel involved in the particular process.

The master transportation planning process provides the opportunity to systematize and improve the "sector" and "neighborhood" sustainable transportation planning process.

Note that such a process would require that sector/neighborhood plans achieve the goals and objectives in the Goals Element of the Master Transportation Plan, which would trump what can be negative and parochial neighborhood initiatives privileging parking and car storage on the street over other modes or against build out of the sidewalk network (see "DDOT sidewalk gap policy has gaps of its own" from Greater Greater Washington).

Finally, ULTIMATELY, DC NEEDS TO EXHIBIT REGIONAL LEADERSHIP AND ELECTED OFFICIALS ESPECIALLY NEED TO ACKNOWLEDGE THAT TRANSIT AND SUSTAINABLE MOBILITY IS THE BASIS OF THE CITY'S COMPETITIVE ADVANTAGE AND POSITION WITHIN THE METROPOLITAN LANDSCAPE.*

*E.g., Fairfax County wants the Silver Line subway so that Tysons Corner can better compete with DC's Central Business District and Arlington's Rosslyn-Ballston Corridor, which are highly accessible via transit.

Labels: car culture and automobility, civic engagement, transportation planning, urban design/placemaking

2 Comments:

Excellent article !!! Thanks.

IMHO. One of the issues with the DC Area is that there are too many subarea plans and modal studies going on. Everyone is getting in each others way. Examples are: the MoCo transit functional plan (i.e. the BRT System),the new WMATA Master Plan (Momentum), The WMATA Bus Priority Corridor Network Plan, the DDOT Street Car Plan, the new the DDOT MoveDC plan, and of course the overall MWCOG Long Range Plan. And that doesn't even include all of the Virginia, PGCO, and Southern Maryland processes.

Jim Bunch

The next set of articles in a similar vein will be on the WMATA Momentum strategic plan. (The week after that will be the NCPC visitors and commemoration element.)

Post a Comment

<< Home