DC's transportation planning process

Called moveDC, Washington, DC is creating a master transportation plan and the public engagement process for the plan is underway now. There have been some meetings this week (the second stage) including an outdoor session yesterday at Union Station. See the past blog entry, "Resources for becoming a learned participant in the DC master transportation planning process."

I have been somewhat skeptical, because the process has been more focused on what I think of as engagement games and less on substance.

Traffic leaving the city via 14th Street heading towards the 14th Street Bridge, 1937. National Archives photo.

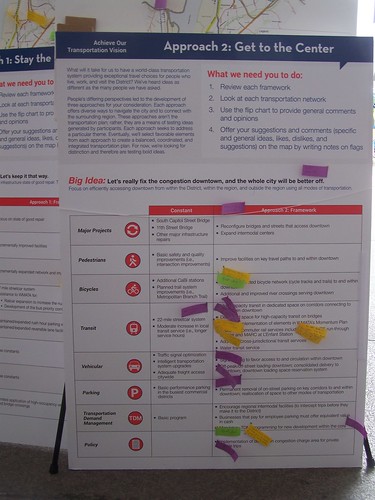

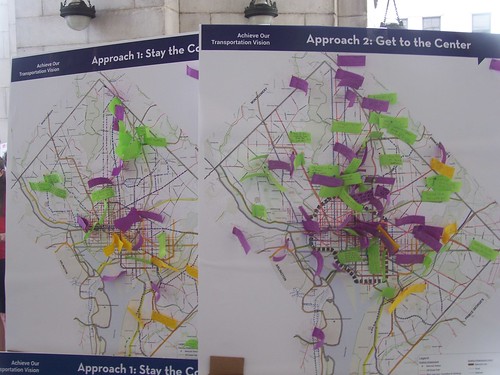

The current round of sessions are framed through the presentation of three scenarios:

(1) "Stay the Course": the way things are now, with lots of "choices" with a value-neutral approach to the choice made;

(2) "Get to the Center": focusing on reducing "congestion" Downtown; and

(3) "Connect the Neighborhood": focusing on intra-neighborhood mobility enhancement for residents, emphasizing short trips (kind of what I think of as "negatrips" along the lines of the Rocky Mountain Institute's concept of "negawatt").

For example, the "congestion" scenario misses the point that the reality is (1) only a few of the streets are permanently congested (K, I, especially, other streets at other times, New York Ave., 14th St., M Street, etc.) because of the limited number of entry-exit points in the city; (2) plus the real congestion now is on the subway.

On the other hand, the city can't neglect the needs of the core, as the Central Business District drives the local economy, is the source of more than 20% of the city's property tax revenue, serves as a major destination for visitors, etc.

And the scenario of non-optimal/value-neutral choice is obviously defective because of how other factors in the "system" "shape" the choices that people make, often towards choosing the car. But people think that driving is a kind of result from "natural law" neither recognizing nor accepting that the current mobility system and its priorities and privileges has been constructed from a set of policy, financial, regulatory, and development decisions.

People think that sprawl is natural rather than as the outcome of a defined system and set of structured choices.

The range of scenarios presented is incomplete

I was somewhat unsettled because the range of scenarios is significantly incomplete, leaving a lot of ground under-covered, even if the "framework" of policies for each of the modes under each of the presented scenarios is decent.

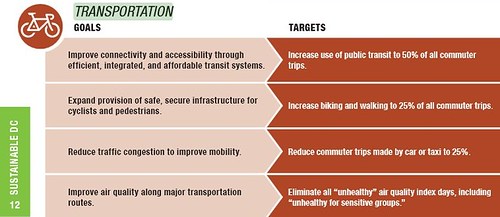

To be "complete" there should be five scenarios. One should be a total commitment to urban mobility-sustainable mobility, as is called for in the DC Sustainability Plan, which sets a goal of 75% of trips--that's all trips, not just work trips--to be made by sustainable modes by 2030. And this scenario would include a focus on making optimal choices, not any choice, choices that support urban-city living, rather than diminish such.

Another way to think about this would be how the Goals and Policies element of the Arlington County Master Transportation Plan outlines an overarching Vision and goals and policies to implement the vision. Goal 2 in particular: "Move More People Without More Traffic," is especially relevant.

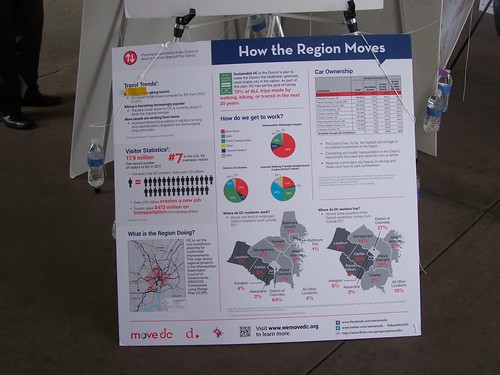

Given that the city is steadily adding population after a multi-decade decline, to the point where city officials are speculating that it's within the realm of possibility for DC to reach 800,000 population in a couple decades, adding people without adding traffic is imperative--especially because even slight, marginal increases in motor vehicle traffic can have cascading negative impact on vehicle throughput.

Transportation goals in the DC Sustainability Plan.

The other scenario should be a pro-automobile, suburban-centric mobility paradigm, focused on separated uses and automobile dependence. People may say that they don't think "suburbanistically" when it comes to center city transportation planning, but most people, whether or not they recognize it, are imprinted with that mobility paradigm, and all too frequently they attempt to apply it to decidedly urban situations.

This was reflected in the economic development transition team's agenda for the Gray Administration. Their policy proscriptions were mostly focused on easing automobile commutes into the city.

Even as a straw man argument, it's important to present it, if only to show the course that the city shouldn't be choosing--and to identify how many ways in which the city is promoting suburban-style mobility policies and practices.

Rockville Pike as the culmination of the achievement of the suburban mobility paradigm, Montgomery County, Maryland. Washington Post photo.

If sustainable mobility were really the preference, goal, and priority of the city (cf. the DC Sustainability Plan) then decisions that various agencies make concerning mobility would be congruent with achieving this outcome.

Often they are not--including not presenting a scenario within the transportation planning process dedicated to achieving the sustainable mobility goals of the DC Sustainability Plan.

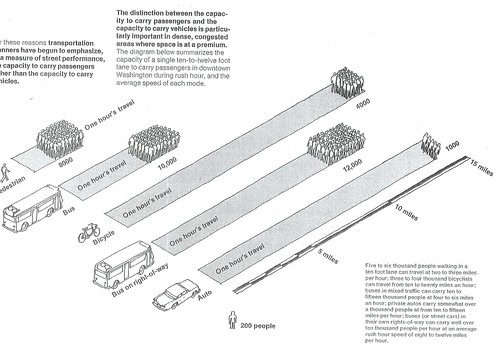

The physics of mobility efficiency. From the Central Washington Transportation and Civic Design Study, 1977. What I think of as the physics of mobility is thinking about a car as a 150 s.f. box carrying one person vs. the 400 s.f. box bus carrying 50 people or the 600 s.f. box bus carry 80 people, etc.

People need to be presented with information on transportation economics in order to understand tradeoffs, constraints, and opportunities

The general point is that people ought to be exposed to urban economics and agglomeration economies and how urban advantages are heightened by sustainable mobility. They need to understand how exchange is facilitated by proximity, how worldwide, the wealthiest metros tend to be less dependent on the car (Newman and Kenworthy, "The 10 Myths of Automobile Dependence"), etc.

With regard to the issue of transportation enabling exchange probably the work of David Engwicht, especially Reclaiming our cities and towns, is the most straightforward, including excellent diagrams of how when more space is devoted to roads and cars less space is provided within which for people to connect. From a book review:

Engwicht maintains that cities were originally created as places for people to come together to trade goods and stories. A city, by definition, can be seen as a concentration of exchange opportunities. Cars get in the way of these exchanges in several ways. They drive people out of public spaces and create inhospitable environments for social interaction because of noise, fumes, and the barrier effects of the stream of traffic. Furthermore, they eliminate what he calls the "spontaneous" exchange — the unplanned encounter — thereby depriving cities of their essential spontaneity and life.

Traffic also sets into motion a wide range of self-reinforcing inefficiencies, according to Engwicht. Cars require roads, which require space, which require urban expansion, which requires more travel, which in turn requires more space.

Engwicht's points set the stage for recognizing that transit is the foundation of the city's economic competitiveness and livability.

Elected officials, residents, and other stakeholders need to understand and appreciate that DC's primary competitive advantage in the context of the metropolitan landscape of commercial and residential choices is its rich transit infrastructure--complemented by support of walking, biking, bike share, and car share--which allows people to get around relatively efficiently without having to own a car.

People need to be presented with information on transportation history in order to understand tradeoffs, constraints, and opportunities in terms of the past, present, and future

In fact, I think transportation plans should have both a transportation economics and a transportation history element. Baltimore's land use master plan has a history element. It's not complete, but I think it's a good first pass, and an example that transportation plans should take to heart. (Frequently, historic preservation plans have a history section.)

In terms of history, stakeholders need to understand how transportation technologies have shaped spatial patterns and mobility choices generally, and in terms of DC and the metropolitan area specifically.

The long term exhibit at the National Museum of American History, "America on the Move," does a good job of explaining this as well. The National Building Museum had an excellent exhibit on this topic around 2002-2003 also, "On Track: Transit and the American City." ("How mass transit and cities grew: Builders made rail lines; Traction firms made communities | A new exhibit in Washington examines their relationship.," review from the Philadelphia Inquirer)

The spatial plan and road network bequeathed to the city by the L'Enfant Plan sets the stage even today, especially as it relates to sustainable mobility--walking, biking, and transit. See "Transportation and Urban Form: Stages in the Spatial Evolution of the American Metropolis" by Peter Muller.

What makes DC different than San Francisco in terms of transit capture, especially for work trips, is the continued concentration of the federal government in DC, proximate to Metro stations, combined with the provision of the federal transit benefit--which means that transit users get all or a portion of their transit costs covered. That's an important historical fact as well, as is how Congress ordered the dissolution of the streetcar system, etc.

There is a tremendous opportunity to reframe public engagement and transportation master planning processes around achieving livability and quality of life improvements through investments in transportation infrastructure

This is a concept I am still developing. And I need to develop it via a full-blown position paper.

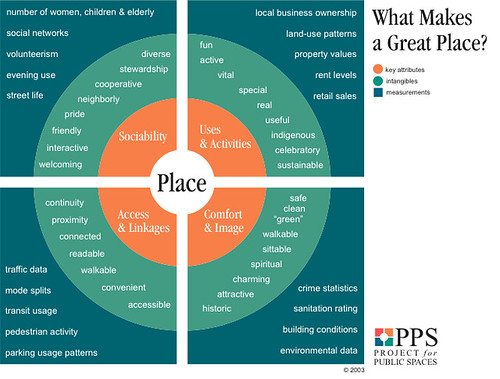

It takes the idea of using placemaking as the framework for citizen engagement in transportation planning more generally.

The basis is how I laid out the "Signature Streets concept" as an integrated design-social marketing-branding-program delivery-funding mechanism in the Western Baltimore County Pedestrian and Bicycle Access Plan.

At the end of the blog entry, "From the files, transit planning in Baltimore County" I develop the concept a bit more. I came up with it at the end of the Balt. County process and didn't have the time to fully develop the approach. I laid out the foundations in this entry, "Complete places are more than complete streets."

But it's also shaped by the Livable Streets program in San Francisco ("It's time for a new 'city beautiful' movement in DC"), new developments in complete streets planning in Chicago, various public space initiatives in New York City, tactical urbanism and the design process, work by the Project for Public Spaces, etc.

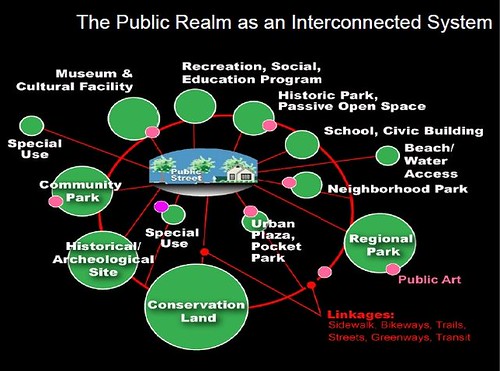

Plus, the PA-NJ Smart Transportation Guidebook, the Oregon guide "Main Street: When a Highway Runs Through it", Barth's integrated public realm framework, and some really interesting points laid out by the Passaic County NJ planning director in their transportation plan, to use planning for heritage corridors--not just roads, but canals, railroad infrastructure, and rivers too--as a way to move tourism forward, which is a different form of placemaking also.

Public Realm as an Interconnected system, Slide from presentation, Leadership and the Role of Parks and Recreation in the New Economy, David Barth and Carlos Perez, AECOM.

People need to be presented with a range of best practice examples and case studies, otherwise the options, ideas, and innovations that are considered is crippled

Mostly people's suggestions at the planning meetings are what I would call "tactical"--where to put a bike sharing station, or to finish the Metropolitan Branch Trail--rather than strategic, such as not only should the Metropolitan Branch Trail be finished, which many people suggest, but also that the city (and region) should create an integrated system of bikeways, comprised of off-road trails and cycletracks, to support the 60% of people who say they are willing to bike but don't, because they don't want to ride in high traffic/high speed traffic situations.

Some bigger "strategery" ideas were offered though.

But people need to be exposed to a wide range of ideas and solutions in order to be able to think more creatively about possibilities and opportunities.

I feel strongly about this because of my experience in co-leading a workshop a couple years ago in Baltimore, focused on improving neighborhoods through transportation improvements.

I didn't speak on biking, but on placemaking. The person tasked with biking was told to only discuss new developments in infrastructure. So he didn't discuss or show images of trails.

In the breakout sections where the groups worked with maps etc., and made suggestions for improvements within their neighborhoods and across the city, no one brought up trails (shared use paths) as an option, even though Baltimore has one great trail (Gwynn Falls) and is developing another (Jones Falls).

Best practice examples prime the pump of what is possible.

I was thinking about what would be mobility comparisons for DC, because cities like London, Paris, and New York City are so much bigger, that comparing those cities to DC isn't really appropriate.

Here are some best practices that come to mind that people need to be exposed to as part of transportation master planning processes:

(DC has a couple I haven't listed, like bicycle share, and as of about 2003, the city's streetscape improvement program was best practice, although since then the practice hasn't kept up with innovations elsewhere)

- San Francisco (bus, streetcar/lightrail, heritage streetcar, cable car, heavy rail/BART, Caltrain, Amtrak) + SF is smaller than DC physically with a population more at what DC's shooting for 800,000+, in fact it's probably the best example

- Philly and Montreal in terms of how railroad passenger services are more like London and Paris in how railroad and heavy rail service can be complementary, how railroad service in Philadelphia especially serves neighborhoods

- Montreal and biking (extensive network of cycletracks)

- best practice walk promotion orgs like Feet First and WalkBoston

- Washington state's walk/bike to school, Boulder's walk/bike to school, Minneapolis Safe Routes to School citywide plan

- various citywide/regional bikeways plans (+ the Dutch and Danish "cycle superhighways")

- streetcar examples -- heritage (Tampa) + modern (Portland)

- fareless squares (mostly going by the wayside because of funding, but still extant in Salt Lake City, Pittsburgh, and Calgary)

- intra neighborhood bus services (Tempe Orbit)/RideOn as a model to think of providing service within certain spread out areas (Ward 3, Ward 8, Ward 7)

- how the Steelers and a casino are paying for operations for the light rail extension to Northside Pittsburgh so that people can ride it for free

- how other transit systems do marketing (including ties in for sports events--Metrolink, MTA)

- the CNT stuff about the link between Transportation costs and mortgage costs

- double deck buses

- best practice bike facilities (air, counters, high capacity parking, protected parking)

- best practice visitor transportation (Savannah, etc.)

- best practice transportation information provision (Arlington, Seattle, Portland)

- nite owl services

- dedicated busways/does any city at its core have a dedicated set of transitways

- Paris addition of light rail (circle line)

- SF Transit First policy

- the equity concepts from Toronto's "Transit City" plan

- parking wayfinding systems (San Jose, Charlotte, etc.)

- a wee bit of ITS

- WMATA's study of trip capture from development proximate to transit

- Hoboken's (yes, they do a better job than DC) use of car sharing and other methods to reduce demand for car ownership and demand for residential street parking

- concept of bike friendly business districts

- best practice TDM (Whatcom County, Washington)

- shared delivery services (so people don't feel obligated to drive to shop, so that they can take home their purchases)

- transportation information centers including Arlington's Commuter Store

- DC merchants' old "park and shop" program of validated parking

- municipal parking systems

- how much MoCo charges for a monthly parking permit in their garages

- Reno Retrac as a model for reconstructing the surface of the under-roadway tunnels (like North Capitol or around Dupont Circle), "Tunnelized road projects for DC"

- King County, Washington transit service metrics

- Vancouver Translink bicycle facilities planning documents

- time shifting freight deliveries (e.g., how much congestion would be avoided if CVS would shift most of ts deliveries to the overnight hours)

- reconstruction of Thomas Circle/Logan Circle

- SF's parklet program/Livable Streets program

- NYC 20mph neighborhood zone program/Montreal's 30kph-40kph-50kph program/Chevy Chase also has 20mph on residential streets

- Alexandria's HOV2 on Washington Street/Rte. 1 during rush hours

etc.

Labels: change-innovation-transformation, civic engagement, design method, participatory democracy and empowered participation, sustainable transportation, transportation planning, urban design/placemaking

10 Comments:

I've always felt that a good model for DC is Brussels. Not neccearily best practice, but dealing with a overly educated workforce, a transnational goverment, and extermely divided regional politics. However, in terms of best practices is probably just bikeshare.

Also, you're a bit too quick to dismiss the transition report. Having people at interesections downtown to monitor and move traffic would help a lot. As would removing certain bus stops. Honestly, half the traffic problems at rush hour on K st are the commuter buses.

Also, moving more jobs outside of Downtown (or L'enfant) would help. We are slowly pivoting east. For whatever reasons jobs are leaving Georgetown and the West end/Golden Triangle. For istance replacing public housing in Columbia Heights with office buildings would be a good start, and open "walking" to work to a whole new population.

(That being said, can planning like this be so micro? I mean there are reasons why the Golden triangle has a lot of vacant/underused space)

Also, while you can get away from commute mode share but it comes and bites you on weekends. Certainly traffic in parts of the L'enfant city are WORSE on nights/weekends than during the day or rush hour.

1. Haven't been to Brussels, but I see how it could be a good comparison size-wise and in terms of the govt. presence.

2. My list of best practices was necessarily cryptic. The line on "a little bit of ITS", ITS meaning intelligent transportation-traffic systems actually for me encompasses what you said about eliminating unnecessary chokepoints in the system that have cascading negative effects.

I first started thinking about this seeing an accident at Adelphi Rd. and U. Blvd., and how it f*ed up traffic almost all the way to E-W Hwy. There were cops and stuff at intersections, but doing nothing to divert traffic east-west rather than continuing to send it north. It got only worse at Northwestern High School.

This happens all the time in DC when they block roads for emergencies. Once, a very rare time that I drove Suzanne to work, N. Capitol was blocked around Michigan ave. and separately at Rhode Island. I knew the network well enough to get off and go west through the neighborhood streets. Most other people, not living in DC, did not.

3. I don't know about decentralizing office. For clustering, people want to locate where other people are. That's what accounts for Georgetown not being much of an office district. I don't know about the West End/GT. Is it losing out to NoMA and M St. SE because those areas, even without cachet, are still closer to the Capitol area, whereas from GT/WE it is 15 to 25 minutes in traffic.

4. cf. Rosslyn, etc. You still have the general shifting of more back office functions from high cost property in DC to NoVA, not unlike the relationship of Jersey City or Brooklyn to Manhattan.

All these things combine to make predicting the future difficult.

5. So the problem with places like Columbia Heights is for them to be competitive they have to attract tenants that want to be in the city but don't need to have 15 minute access to Capitol Hill.

Are tenants like that still willing to locate in CH for some but comparatively minimal amenities and rents not a lot cheaper than in the CBD?

Great question. It's like MoCo's Wheaton question.

Note also that office uses are declining in Silver Spring too.

I think there is a big focus on recentralization, as more people "hotel", organizations cut back on s.f./employee, more people telework or work on a consulting basis, etc.

Now if you centered some cool anchoring institutions in these noncentral places like Columbia Heights, e.g., tech and other business incubators, a 3-D printing operation, operations like the 3rd Ward in Brooklyn and Philadelphia, etc., maybe that's a way to make them become in-demand.

In terms of best practices, I would nominate Zurich as a model for the District.

In terms of clustering, yes. Applying it to DC you've got the problem of prestige (DC jobs tend to more prestige focused than other cities, notice the heavy emphasis on lobby space) and also GSA and their limits.

But I don't see why CH can't be as "back office" as Rosslyn was. Navy yard is another example.

Larger point I'm trying to make -- compared to the R-B corridor most of DC outside of downtown is deserted during the day.

... wrt your last point, yes. Why do you think that is? The college helps, so does the fact that there is a lot of residential there.

rg -- I thought about that but decided mostly to stick with North American examples. My understanding is that Melbourne would be a good comparison too. I've never been to Australia though, nor Zurich.

That makes sense. I have never been to Melbourne, but would love to visit. Its streetcar system is fantastic and I understand it is an otherwise wonderful city. I have been to Zurich and was amazed at the coverage and efficiency of its streetcar network. I think it is generally about the same scale as DC.

Not sure if the 11:55 comment was directed at me, but I think R-B is busier during the day because office buildings are spread out along the entire corridor.

(it doesn't explain why lunch options are so bad, though)

between shaw, U st, and columbia heights, for instance, the number of gainfully employed people during the day is incredibly small.

Also, the growth of flex office space is tremendous right now.

RL-

Fab Foto from 1937--talk about evidence of incompetence!! Nothing has changed in 75 years. In fact, it's gotten worse.

It's time for the feds and DC to stop the game-playing and giveaways and develop housing in DC for their workers so they can stop commuting from MD and VA and become DC residents.

-EE

Thanks for sharing helpful source. Keep sharing good work about travel data analytics.

Post a Comment

<< Home