Minneapolis-St. Paul: second light rail line opens

New Green Line light rail on University Avenue in St. Paul, Minnesota. Photo: Ben Garvin, St. Paul Pioneer-Press.

The St. Paul Pioneer-Press has run articles all week about the opening of the new Green Line light rail line in that city--it opened on Saturday ("Green Line debut: 45,000 rides and just as many memories" which includes a great photo gallery).

The line complements the Blue Line from the Airport to Downtown Minneapolis, which opened in 2005 and has about 33,500 daily riders, which is about 50% higher than what was projected to be achieved by 2020.

One of the articles ("Green Line opening will bring out protesters as well as riders") is about protesters who were planning to come out to the launch, out of their concerns for the cost of building the system, use of tax money, and cost of annual operations. I thought that was interesting, because I haven't heard of that happening very much elsewhere. (Of course, they are a bit blind to the subsidy of the road network, which commenters on the article have pointed out.)

The new Green Line runs in

On the University of Minnesota campus, where the light rail line replaces a formerly auto-engorged road, there is concern about pedestrians and cyclists not paying enough attention to the trains, which will run through the campus 24 hours/day ("Heads up at U: A train is coming," Minneapolis Star-Tribune, Big differences between light rail lines," KARE-TV).

Revitalization in St. Paul. A primary goal for the line is the revitalization of University Avenue, which has declined ever since the Interstate Highway opened, which diverted traffic away from the city.

Like in Arlington County, Virginia, the decision was made to route the transit line through the city, rather than around it, in order to achieve community improvement while simultaneously enhancing mobility.

St. Paul too has less economic energy compared to Minneapolis, being more of a government center, plus Minneapolis has the bulk of the University of Minnesota's Twin Cities campus, which is one of the largest university campuses in North America (and the transit line will go through part of the campus, although accomplishing this was quite contentious).

-- "Will Green Line bring prosperity back to University Avenue?," Pioneer-Press

-- "Past battles aside, UMN sees bright future in Green Line," Pioneer-Press

-- "St. Paul makes a bet on revival with Green Line light-rail train," Minneapolis Star-Tribune

-- "Four Green Line stations to watch," Finance & Commerce business review

Having the transit line will help to begin rebalancing economic and residential activity between Minneapolis and St. Paul but at the same time will help to recenter economic activity on the core of the region.

Complementing the light rail line, St. Paul is planning a streetcar line and has upgraded the Union Station railroad depot, which is used by Amtrak and is the terminus for the newly opened light rail service in St. Paul.

From the St. Paul Pioneer-Press editorial "Green light for the Green Line":

Along the line, more than 100 projects -- representing more than $1.7 billion in private development -- have been built, are under construction or are in planning phases, according to the Metropolitan Council. Employment along the line is projected to grow by more than 90,000 jobs by 2030.Are transit lines community destroying? Interestingly, a search of the blog archives finds something I wrote in 2006 (and have no recollection of writing) about opposition to the expansion of light rail to St. Paul out of a fear that--recognizing that the construction period for infrastructure is long and wrenching for impacted businesses, many which fail as a result--the impact would be as negative as the interstate highway system was to cities, not only in terms of destroying neighborhoods in the path of the roadway, but in improving access to the increasingly popular suburbs, which fostered population outmigration from the center city.

-- "Nimbyism, fear of improvement, fear of change"

The system agreed to add stations in response to community demand, but the number of expected daily riders from the stations is pretty low... but at least you have communities demanding access (this also happened in Leimert Park in Los Angeles, "L.A. leaders call on MTA to put rail station in Leimert Park Village [Updated]," Los Angeles Times) rather than trying to avoid it (e.g., in Anne Arundel county in Maryland, "Some Linthicum residents want to close light rail station over crime," Baltimore Sun).

-- "Planning for transit lines: trip speed vs. access and station density"

Right: This Pioneer-Press photo shows the transit mall going through the University of Minnesota campus. The way the line has been integrated into the street-urban fabric there is an example of using urban design principles to maximize positive benefits from transit infrastructure.

The evolution of fixed rail transit planning in the US: urban design and transit equity. It is true that the original impetus of modern, first generation, fixed rail transit planning (BART in the San Francisco Bay, WMATA in greater Washington, MARTA in Atlanta, etc.) wasn't urban improvement as much as it was facilitating the movement of suburban residents to jobs located in center cities. And second generation attempts, light rail for the most part, in cities like Buffalo or Baltimore, haven't been effective at urban improvement either because for the most part they were single lines and the stations weren't placed well.

With third generation attempts (such as light rail in Denver, and streetcar lines in cities like Portland, Oregon) there was a much more nuanced focus on linking transit access to a city's activity centers in ways that promote intra-city mobility and resident and business attraction and physical development (such as of vacated land parcels like railyards).

Left: Nine kiosks like these will be placed at nine light-rail stations on the new Green Line. The aim is to alert riders about access to nearby connections. Photo: Jim Anderson, Minneapolis Star-Tribune. See "Green Line light-rail info kiosks work on two levels."

And what I call fourth generation efforts in Minneapolis and Seattle (2005 Seattle Times story "MLK way") and for the Purple Line in Suburban Maryland ("Purple line planning in suburban Maryland as an opportunity to integrate place and people focused initiatives into delivery of new transit systems" and "Quick follow up..."), there is a much greater focus on ensuring that transit equity elements are accomplished and integrated into the planning program from the outset, so that lower income households benefit not just equally, but greater, compared to early transit infrastructure building efforts.

Urban design. Part of this comes from how the stations are integrated into the community fabric, and if they are designed from the outset to complement and connect rather than disconnect and ignore. Disconnection is the more typical result, because infrastructure engineering has been focused on producing the cheapest outcome, rather than the best or multiple outcomes.

-- past blog entry, "Transit, stations, and placemaking: stations as entrypoints into neighborhoods"

-- The CTS report, Transportation as Catalyst for Community Economic Development has a robust framework for high-quality transit line and station planning and decision-making.

-- Green Line Walkability | District Councils Collaborative

The second light rail line is additive and the metropolitan area begins to create a fixed rail transit network. Observationally, I would argue that there is a strong likelihood (as opposed to "good chance") that University Avenue will revive over time, as development is attracted to transit proximity, because the line serves major destinations in the metropolitan area, and as the line is complemented by the existing blue line, so that the area is beginning to develop a fixed rail transit network, rather than merely having a single line--single transit lines have some benefit but you don't begin to see transformational impact until you have a fixed rail transit network.

A commitment to sustainable transportation is already in place. Minneapolis-St. Paul already has a strong bus network, and Minneapolis in particular has a particularly strong rate of cycling for transportation and an extensive bikeway network, as well as some of the nation's best bicycle and pedestrian master plans and a citywide Safe Routes to School program strategic plan, a bike sharing system, and some innovative advocacy groups, including Twin Cities Streets for People (and also some top notch community economic development corporations such as the Neighborhood Development Center whose director, Mike Temali, has authored an excellent text on the subject, Community Economic Development Handbook).

The Freewheel Midtown Bike Center is a bike shop that opened on the Midtown Greenway Trail and is a great example of integrating service facilities within physical infrastructure. Star-Tribune photo.

It helped that when local Congressman James Oberstar chaired the House of Representatives transportation committee, that Congress funded a Nonmotorized Transportation Pilot Program and Minneaspolis -St. Paul was one of four participating cities, and this helped to build the foundation for sustainable transportation, especially biking and bike sharing.

The University of Minnesota/Center for Transportation Studies. Plus, the University of Minnesota's Center for Transportation Studies is one of the best university centers focusing on transportation-related research and practice.

Oh and the Minneapolis Design Center of the College of Design does a wide variety of neighborhood and commercial district based projects in the metropolitan area and across the state.

Maybe because so many of the elected and appointed officials in the metropolitan area attended UMN, there is a great deal of knowledge transfer between CTS (they also run state-wide training programs for the Minnesota Department of Transportation), the Hubert Humphrey School of Public Policy, and other academic units and local governments.

CTS academics have done a great number of studies that include the original light rail line (now called Blue, originally Hiawatha) as one of the units of analysis.

-- Transitways Impact Research Program

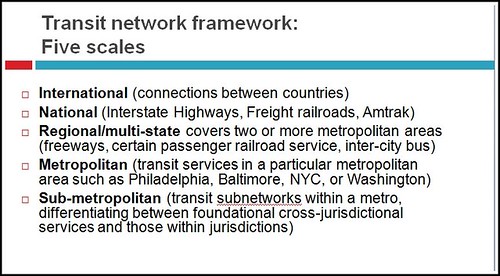

Slide from a presentation I gave at the University of Delaware on Metropolitan Mass Transit Planning.

Transportation investments: exurbs vs. the center city. I have a piece about intra-city transit ("Making the case for intra-city vs. inter-city transit planning") that emphasizes the point that intra-city mobility is a different type of transit service than inter-city mobility or moving people between the city and suburbs and within the suburbs. I

I also have written extensively on the distinction between metropolitan and regional transit service--regional transit service connects different metropolitan areas--and planning transit and the metropolitan and sub-metropolitan scales ("Metropolitan Mass Transit Planning: Towards a Hierarchical and Conceptual Framework," "Without the right transportation planning framework, metropolitan areas are screwed, and that includes the DC area," and "Second iteration, idealized national network for high speed railpassenger service").

Photo: Jason Wachter, St. Cloud Times.

As the Green Line opens, the St. Cloud Times has an editorial, "Our View: Green Line begs asking, ‘Why not us?’," making the point that for much less than the cost of building the new light rail line, they could have been connected to Minneapolis by commuter railroad, implying that would have been a better investment--St. Cloud is 65 miles from Minneapolis and has a population of 65,000.

Original plans for the line intended to include St. Cloud, but the ridership projections weren't high enough to qualify for federal funds, so the project was shortened, although St. Cloud is still on the horizon for expansion of the line.

From the editorial:

At a cost of $975 million, the Green Line covers 11 miles and includes 23 stations.The one line of the Northstar commuter line that exists currently is 40 miles long and has about 2,400 riders per day, projected to reach not quite 6,000 daily riders by 2030. The inter-center city Green Line will likely have at least 20,000 daily riders now, which is projected to reach levels of about 45,000 daily riders in 2030.

When originally proposed in 1998 — and three years before Green Line plans really took hold — building the Northstar line from Minneapolis to Rice would have cost $146 million. Even 11 years later, when a reduced Northstar opened from Minneapolis to Big Lake, it cost $320 million, included seven stations and covered 40 miles.

So for a third of Green Line’s costs, Northstar covers almost four times the distance.

So there are two questions. One has to do with planning and funding different types of infrastructure for the different types of mobility needs. The other has to do with use and impact and policy objectives. Generally, the spillover economic benefit of commuter-oriented transit is significantly less compared to transit systems that balance community access with suburban service.

Ultimately, the answer is determined by the number of riders served and the return on investment, not about the number of line miles in the system. ... and as a report from CTS makes clear, the biggest benefits from transit service come from the core of the system, not the extensions (The Hiawatha Line: Impacts on Land Use and Residential Housing Value).

From the standpoint of smart growth and minimizing overall investment in infrastructure, it makes more sense to support metropolitan intensification (along the lines of the arguments in Belmont's Cities in Full) and centralization than to promote exurban development through expansion of commuter railroad service.

To evade that reality, the St. Cloud Times editorial focuses on the length of the respective lines--distance in miles--rather than the number of riders.

I have written about this quite a bit in terms of Maryland, and how stakeholders see all "transit stations" as having equal opportunity for growth and intensification when the reality is that distantly located commuter rail stations don't have the same opportunity stations closer in to the core. See "What the State of Maryland still doesn't get about smart growth" and "Bad Montgomery County policy/law initiative #1: removing density bonuses for building around MARC train stations."

(Although one way that benefits are lost in the DC region, at least in close-in stations in Montgomery County, is that the MARC line to Frederick/West Virginia doesn't support reverse commuting--which would make sense for Rockville and Gaithersburg.)

That being said, it doesn't have to be either-or, although in times of limited financial resources, choices have to be made about where to invest, and usually these decisions are made in terms of overall economic impact. Intensity promoting transit infrastructure investments tend to have the best economic return.

I like this graphic that the Metro Transit system has created to promote the new transit line. Inside the circle are things and places you can go. The stations-places on the line are listed on the rim of the circle.

Labels: equity, fixed rail transit service, transit and economic development, transportation planning, urban design/placemaking, urban revitalization

3 Comments:

The Green Line does not run in mixed traffic, it is entirely in dedicated right of way. However, unlike the Blue (Hiawatha) line, it is mostly in the median of University Avenue. It does not share space with cars, but does have to deal with cross streets, just like Hiawatha.

urgh.

Thank you for providing such a valuable information and thanks for sharing this matter. to get Online pharmacy from online medicine store.

Post a Comment

<< Home