(Public) History/Historic Preservation Tuesday: Museums and Modern Historiography

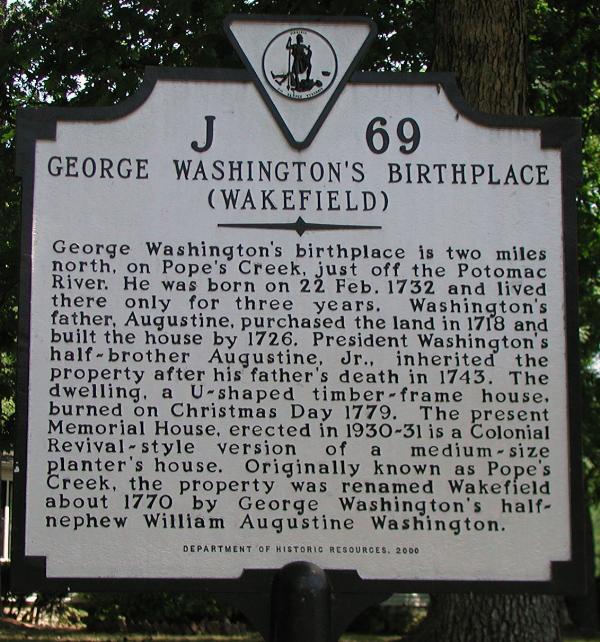

Last weekend we went to the George Washington Birthplace National Monument, in Westmoreland County, Virginia.

Interestingly, it is a re-created place, not unlike Colonial Williamsburg, and both places share John D. Rockefeller Jr. as a donor. Rockefeller gave money to the Birthplace a few years before he was enticed to fund the preservation and re-creation of Virginia's original state capital.

It was interesting that the bookshop had a couple of titles that challenged the mythology around George Washington, and the exhibit, while very simple, started off with a section on "myth vs. fact" about George Washington.

The books, Here, George Washington Was Born: Memory, Material Culture, and the Public History of a National Monument and Inventing George Washington: America's Founder, in Myth and Memory, discuss the role of George Washington as an element of nation building and the national "story" and mythology around the founding of the United States of America, and the promotion of patriotism.

Last year, visiting Gettysburg, I was spurred to read a bunch of books about the Civil War, having been first primed a few years before by the Valentine Richmond History Center in Richmond, Virginia, and their exhibit on the historical themes of the city, which pointed out that during the Civil War era, Richmonders--remember that their city was the capital of the Confederacy--voted against entering into war with the Union.

Modern historiography of the Confederacy makes hash of the "Lost Cause" myth. Even I remember reading one of the chapters of Barrington Moore's Social Origins of Dictatorship and Democracy: Lord and Peasant in the Making of the Modern World in my sophomore year in college, and how "the Civil War was necessary to make over the US as a modern industrial economy."

But that interpretation still hasn't percolated down much within the South more generally. One example is the City of Petersburg, Virginia and its presentation of various Civil War sites under the control of the city.

Confederate flag. Given that a nation's flag is very much a symbol, the ongoing controversy over display of the Confederate flag is another example of the clash between reflexive "patriotism" and an unwillingness to consider all relevant elements of said symbol vs. considered reflection. How can the flag of the Confederate States of America not be seen as a relic of racism and slavery?

More recently, the Danville Museum of Fine Arts and History has gotten caught up in this controversy. Danville was the last "capital" of the Confederacy, and the Confederate flag flies on the Museum's grounds.

The Museum's strategic plan calls for presentation of an inclusive history and so the display of the flag is seen as incongruent with their goals and objectives and they requested from the city permission to take it down. That has touched off great controversy and the local newspaper has a great number of articles about it (e.g., "Museum marches on with upcoming sesquicentennial commemoration," Danville Register-Bee ).

From the article:

The newly adopted strategic plan includes a vision “to be the Dan River Region’s leader for integrated awareness of history, culture and community,” according to a Sept. 30 letter from Board of Directors President Jane Murray to museum members. ...The comment threads are particularly interesting and there have been a number of pro- and con- letters to the editor as well (e.g., "Confederate flag must come down").

Burton, in a Sept. 30 letter to the city, asked Danville City Council to remove the flag from outside the building to inside for an upcoming exhibit of the history of Confederate flags. The museum’s board of directors had voted Sept. 25 to make the request as part of its new three-year strategic plan.

The request caused an uproar among Confederate heritage organizations and other supporters of keeping the flag on display outside the museum. The move re-ignited a debate between flag supporters and those who see the flag as a racist reminder of past enslavement of African-Americans.

During an interview Friday, Burton said the Confederate flag exhibit that will be part of the sesquicentennial will go on as planned. People have “politicized the flag,” she said, but the museum’s board is merely trying to be inclusive and welcoming to everyone.

Right: Georgia II by Leo Twiggs.

By contrast, there is an exhibit of paintings by an African-American artist at the Greenville (South Carolina) County Museum of Art ("SC artist sees heritage, hate in Confederate battle flags," Greenville News).

From the article:

Some see heritage. Some see hate. When artist Leo Twiggs looks at the Confederate battle flag, he sees both of those things — but also a vision for a more harmonious future.

Twiggs' 11 large depictions of the flag at the Greenville County Art Museum are at once beautiful and tattered, reflecting a shared Southern history of pride and pain.

"In our state, I think the flag is something that many black people would like to forget and many white people would love to remember," Twiggs said. ...

Through the repeated image of a torn and tattered flag, Twiggs addresses subtle issues about the shared Southern history of African Americans and whites, and the continued complexity of race relations.History curriculum not patriotic: Colorado. While interrogational historical interpretation is accepted in the academic world, it is still controversial in the K-12 educational arena, as witnessed by the recent proposal by a local school board in Colorado to make over the district's AP history curriculum because they didn't believe it is "patriotic" ("Changes in AP history trigger a culture clash in Colorado." Washington Post ).

The Board backed down after widespread protest led by students. Image from the AP story "Colorado students walk out in protest,"

Of course, the dichotomy between patriotism and "revisionism" or a broader interpretational framework for history and "social studies" is a major thread in national discourse

Personal history. Speaking of rocking my world, and personal historiography, because of my tragic childhood, I don't have a lot of details about my own ethnicity, although I have some clues, stuff I remembered, which Suzanne decided to follow up. So while I thought half my heritage was German/Russian, it turns out that I am Polish-Russian/Belorussian on my father's side of the family.

And looking at old records of the family, while I thought always that Hamtramack, Michigan, a Polish enclave surrounded by Detroit, was 100% Catholic, the reality is that the area also attracted, at least for a time, Polish Jewish immigrants also. Some of my relatives likely lived for a time in the "Poletown" neighborhood in Detroit that was eradicated in the 1980s for a GM manufacturing plant.

On that note, the Polin Museum of the History of Polish Jews has opened today in Warsaw ("A new Warsaw museum devoted to Jewish-Polish history," Financial Times). The museum's core galleries address the place of Jews in Poland's history, focusing on integration but acknowledging anti-Semitism, recovering memory that was eradicated finally by the Holocaust.

Crowdsourcing museum curation/the public in public history. The Wall Street Journal has a piece on crowdsourcing art exhibits, "Everybody's an Art Curator," which can be controversial when familiarity can trump artistic evaluation and merit. On the other hand some museums have experienced a significant uptick in visitation, membership, and funding when they increase public engagement through such methods.

In terms of community history, I have had some problems with the "everyone's a historian" focus of some of these kinds of initiatives. I do think that historians need to step in when it is warranted and provide greater context, and acknowledge developments in history at multiple scales (commmunity, metropolitan area, region, state, nation, globe) so that important events aren't lost at the expense of the familiar and popular. See the past blog entry "Thinking about local history."

Labels: cultural heritage/tourism, geneaology, historic preservation, historiography, local history, urban history

4 Comments:

I often say that the problem that white Americans have with empathy toward immigrants and migrants is our ancestors did such a thorough job of hiding their own stories. It was survival, blending in. The trauma of fleeing countries and the bullying once they got here. For my own grandmother, whose immigrant parents left upstate NY to head to Canada and then Michigan to escape anti-German sentiments, to be a Republican housewife in West Bloomfield was the pinnacle of blending in. I believe my great grandparents never told their complete stories and how being atheist was a way to renounce their Jewish and Catholic roots in a mixed marriage and a place that didn't regard either well.

Very interesting observation. E.g., Suzanne's grandparents on her mother's side were German immigrants. Their children, including Suzanne's mother, were born here. While the grandparents spoke German, they insisted their daughters speak English, to assimilate, and they don't really understand German today. Of course, the next generation of children have no connection to German.

https://www.sacurrent.com/the-daily/archives/2021/07/03/state-museum-canceled-book-event-examining-slaverys-role-in-battle-of-the-alamo-after-texas-gop-leaders-complained-authors-say

(Sons of Confederate Veterans) Manual advises how to stop removal of Confederate statues: don’t mention race

https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2021/jul/04/sons-of-confederate-veterans-manual-statues-symbols

‘We’re artists, not boxes to be ticked’: Lubaina Himid on her call to arms – and exposing Bath’s past

https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2024/jan/17/lubaina-himid-bath-turner-prize-winner-holburne

ong, vibrant fabrics weave across the front of Bath’s Holburne Museum, looping around its pillars like ribbons. Inside, the cloths unfurl from one end of the ballroom to the other. In one room dedicated to 18th-century British painting, they line the perimeter like waves, drawing your eyes with bursts of colour – transforming the space from staid to something modern and immediate.

“The cloth is occupying the space,” explains Lubaina Himid. “It’s weaving itself into the history of this museum. It’s coming out from the fabric of the building.” There are 400 metres of Dutch fabric in Lost Threads [https://www.holburne.org/events/lubaina-himid-lost-threads/}, one of the artist’s most expansive and dramatic works to date. Each cloth is intended to reflect the movement of the oceans and rivers that were used to transport cotton, yarn and enslaved people – all of which enabled parts of Britain, including Bath, to become increasingly affluent in the 18th century.

Post a Comment

<< Home