An example of using variegated road material treatments in Bothell, Washington

Looking north along Bothell Way Northeast’s “multiway” boulevard in downtown Bothell. The “multiway” boulevard shows faster traffic and a separated lane used for parking, bicycles and business entrances in downtown Bothell. Photo: Steve Ringman, Seattle Times.

The Seattle Times reports ("Fast lane meets slow lane on Bothell's new 'multiway'") about a project on a State Highway that also functions as a city-serving street in the suburb of Bothell, where a five block stretch of street in the Downtown has been reorganized to separate "fast" from "slow" traffic. From the article:

The city took over the lower five blocks of state Highway 527, put up new signs saying Bothell Way Northeast and created a “multiway” that’s like three parallel streets, totaling as many as 11 lanes — a five-lane main roadway, sandwiched by a slow zone on each side where drivers can park or drop off passengers. ...From the description, we could say instead that "through" or regionally serving traffic is being separated from "local" traffic in a manner that doesn't degrade the urban design and placemaking qualities of the street and roadside in terms of how it serves local needs and conditions.

"This roadway is designed to knit together the old historic part of downtown with the new downtown. Previously, the highway was a sort of barrier,” said Steven Morikawa, city capital division manager.

Bothell residents said in community meetings they wanted to keep the walkable vibe of old downtown, Tung recalled. “How would we extend that character, and adapt to the fact we would still have automobiles?” the architects wondered. ...

The slow parking zones are built on concrete blocks that resemble giant cobblestones, with sand in the gaps to drain rainwater. The zones are cordoned by dividing curbs, trees and rain gardens where people walking can pause and look for cars. This effectively reduces the most strenuous of the pedestrian crossings to only five lanes.

While the street seems particularly wide, which is counter to the general principles of placemaking in a Downtown, the concept extends and implements principles laid out in at least two planning documents that come to mind, the Smart Transportation Guidebook produced by the Delaware Valley Regional Planning Commission for the States of New Jersey and Pennsylvania, and the Oregon DOT publication, Main Street: When a Highway Runs Through It.

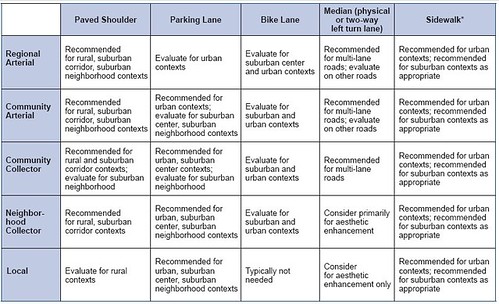

The STG argues one size fits all road construction doesn't make sense, that road and roadside characteristics, desired operating speed, whether or not a road is regionally or local serving, and the land use context ought to shape outcomes in differentiated ways. In short, it's reasonable for a downtown or urban street to be treated much differently from a suburban arterial or rural road.

Similarly, MS:WAHRTI acknowledges that "state transportation department" concerns about how to operate roads can come into conflict with local land use context, especially in traditional commercial districts, and it lays out a framework where State DOTs and communities can work together to achieve better outcomes.

-- American "multiway" boulevard examples, National Association of City Transportation Officials

What distinguishes the Bothell "multiway" from others is the use of differentiated road treatments, whereby other multiways (parkways) use the same paving material throughout.

In DC, I have suggested for many years that "neighborhood" streets with a primarily residential-serving purpose, and streets in pedestrian-centric areas, such as commercial districts, around transit stations, schools, parks, libraries, and other civic facilities, should be constructed of pavements more in line with the desired operating speed of motor vehicles--25 mph or less--when roads constructed of asphalt or concrete typically allow speeds that are double or triple.

-- "What a "Complete Places" land use and transportation planning philosophy would mean in practice," 2008

-- "Complete Places are more than Complete Streets," 2010

-- "It's time for a new 'City Beautiful' movement in DC," 2011

This also illustrates my more recent concept of "Transportation infrastructure as an element of civic architecture," which is described more completely as a sub-section of this post:

-- "Town-City Management: We are all asset managers now," 2015

Streets constructed of asphalt block give visual, aural, and physical cues to slow down, such as on 4th Street NW between the east and west wings of the National Gallery of Art.

While the Bothell roadway isn't fully constructed of block pavers, they are using a mix of roadway treatments, with a block-brick type material to denote "local" streets, in the context of a street that mixes both through and local traffic. While it's probably not an absolute "first," it's clearly an atypical step forward, and more urban transportation departments need to consider greater use of block pavers--which may be used in crosswalks but not streets, or on streets that are adjacent to heritage buildings, such as Washington's Eastern Market.

The street in front of Eastern Market is closed on weekends, much to the consternation of the interior food merchants who constantly advocate for the reversal of this decision.

Brick crosswalks on Pennsylvania Avenue NW at 6th Street

While I believe the STG is in need of a serious update to reflect advances in sustainable mobility practice, it's a great starting point for thinking about roads in terms of appropriate land use context.

Matrix of Design Values for Regional Arterials, From Smart Transportation Guidebook.

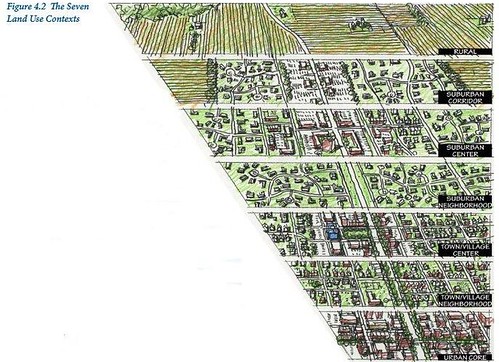

Seven land use contexts for transportation planning, Smart Transportation Guidebook

Cross section elements, Smart Transportation Guidebook

Labels: civic architecture, roads, sustainable mobility platform, transportation infrastructure, transportation planning, urban design/placemaking

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home