World Usability Day, Thursday November 9th and urban planning

I was researching something and along the way, learned that there is a World Usability Day. We most often think of usability in terms of the "user interface/experience" concerning human-computer interaction, but we can think of usability as the key outcome of the design method and process too, especially as it relates to urban planning.

Legibility. In urban planning, it's fair to say that one of the pioneers of usability was Kevin Lynch, who came up with the term "legibility" concerning urban environments and how people make sense of urban places, which he outlined in his pathbreaking book, The Image of the City (this is the whole book via pdf). From Ingram and Benford, "The Application of Legibility Techniques to Enhance Information Visualisations:

Lynch identified five major elements of urban landscapes which were identified by the inhabitants and used as the main building blocks of their cognitive maps. These features are:Other concepts: business process redesign. The method of business process redesign (sometimes referred to as "re-engineering") is a similar approach to usability, although traditionally it focuses on organizational processes and outcomes.

• Landmarks. Static and recognisable objects which can be used to give a sense of location and bearing. Examples of landmarks might be prominent buildings or monuments or, on a smaller scale, recognisable shopfronts or roadside installations.

• Districts. Sections of the environment which have a distinct character which provides coherence, allowing the whole to be viewed as a single entity. Districts may be identifiable, for example, by the nature of the architecture of the buildings in the area or by their use.

• Paths. Major avenues of travel through the environment such as major roads or footpaths

• Nodes. Important points of interest along paths, e.g. road junctions or town squares. There is clearly a strong link between paths and nodes.

• Edges. Structures or features providing borders to districts or linear obstacles. Examples might be the waterfront in cities built on large rivers, or a major road. Note in the latter case that the road may have a dual nature, being a path for someone travelling in a car but an edge to the pedestrian.

I use a form of business process redesign when I evaluate systems and write planning documents. My basic point is that the point of planning and zoning is to "improve quality of life" and when "routine outcomes" don't do this routinely, that's an "indicator" that there is a defect in the process that produces the outcomes.

What I try to do then is look backwards at the processes that produce the regular but undesirable outcomes, and make recommendations for change. Thomas Davenport's book Process Innovation: Reengineering Work Through Information Technology has helped shape my thinking about process redesign and innovation.

Urban design as a usability approach. Over the past 15 years, many planning and architecture programs have added degree programs in "Urban Design," which combines urban planning, landscape architecture, and architecture concepts. The Urban Design website describes the profession thusly:

Urban design involves the arrangement and design of buildings, public spaces, transport systems, services, and amenities. Urban design is the process of giving form, shape, and character to groups of buildings, to whole neighborhoods, and the city.

It is a framework that orders the elements into a network of streets, squares, and blocks. Urban design blends architecture, landscape architecture, and city planning together to make urban areas functional and attractive.

Urban design is about making connections between people and places, movement and urban form, nature and the built fabric. Urban design draws together the many strands of place-making, environmental stewardship, social equity and economic viability into the creation of places with distinct beauty and identity.

Urban design is derived from but transcends planning and transportation policy, architectural design, development economics, engineering and landscape. It draws these and other strands together creating a vision for an area and then deploying the resources and skills needed to bring the vision to life.

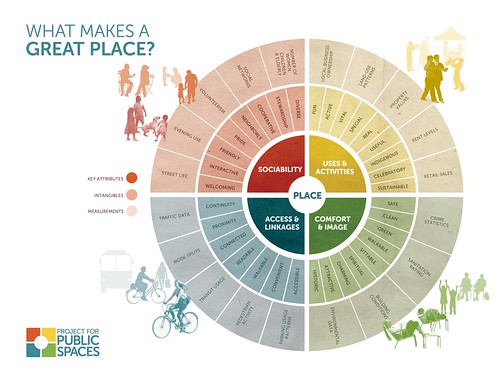

Project for Public Places, Placemaking diagram (flywheel)

Placemaking. You can argue that placemaking is an approach to usability planning in cities also.

-- "What is Placemaking?," Project for Public Spaces

-- Placemaking articles archive, PPS

-- Placemaking booklet, PPS

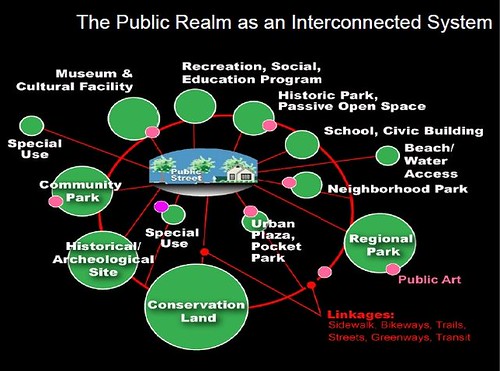

Related concepts that I use are "the integrated public realm framework" and "transportation infrastructure as an element of civic architecture." These concepts are discussed in the organizing framework of what I call "Signature Streets" ("Town-city management: We are all asset managers now").

Public Realm as an Interconnected system, Slide from presentation, Leadership and the Role of Parks and Recreation in the New Economy, David Barth

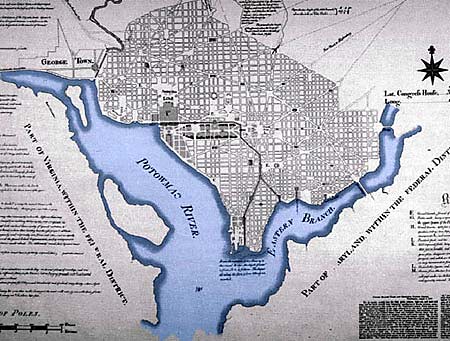

The Street Grid. The grid design for cities, such as the L'Enfant Plan for the City of Washington, illustrates Lynch's argument for legibility and "reading" the city. The grid is organized at right angles, with streets connecting the various "blocks."

Some people get confused, believing that DC doesn't have a grid because it also has avenues which bisect the grid. But radial avenues are a great addition to the grid, shortening the distance between nodes, because you can travel at an angle.

In the design of DC, the key organizing landmarks were the White House, home of the Executive Branch of Government, and the US Capitol for the Legislative Branch. The greenspace of the National Mall connects these landmarks, although the Mall has since become the home to many more landmarks--memorials and museums--and extends beyond these two points.

The reservations--circles and parks--were designed to function as nodes, while the city's rivers were primary edges, and the radial avenues the primary paths, complemented by the secondary paths--streets--comprising the city's various subdistricts.

The London Underground as a design artifact. The London Underground is an outlier for transit systems in that it has been a consistent innovator in design and usability for 100+ years. Key to this development was Frank Pick, who started at the agency being responsible for communications ("PR") and who laid the groundwork for corporate branding by coordinating all elements of the program into an integrated and extensive transit system -- advertising, branding, station architecture, vehicle design, and mapping -- with the highest standards for "design."

Today, that legacy is maintained through the creation of "product design managers" for the various transportation modes managed by the successor agency, Transport for London.

-- Product design guidelines, Transport for London

Chancery Lane Station entrance, London Underground, c. 1930s, with posted Harry Beck Tube map. The new London Underground map seems incredibly modern in the context of London's built environment being dominated by architecture from the previous centuries.

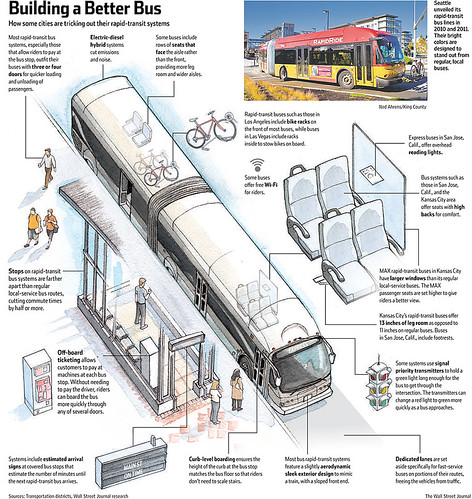

Transit systems and legibility. The creation of high-frequency bus networks, night bus networks ("Night and weekend transit/subway service: Metrorail edition" and "Slight revisiting of overnight transit service: San Francisco"), the program around the creation of true bus rapid transit lines, such as in Cleveland, or the collaborative integration of transit agencies in the Raleigh-Durham area under the GoTransit brand ("Will buses ever be cool? Boston versus the Raleigh-Durham's GoTransit Model") are other examples of applying usability approaches to transit.

Wall Street Journal graphic.

New systems for providing and presenting integrated transit service information, such as the TransitScreen product are other ways to improve usability and use of transit as a mobility mode.

Real time transit information via TransitScreen and the Orange Barrel Media digital billboard outside Capital One Arena, Washington, DC.

Also see "Making bus service sexy and more equitable" and "Is making surface transit free the best transit investment DC can make?."

In terms of usability, transit stations are are frequently under-developed ("Takoma Langley Crossroads Transit Center: A Critical evaluation," "Multiple missed opportunities in creating the Silver Spring Transit Center," "Brief follow up on the Silver Spring Transit Center," and "Transit, stations and placemaking: stations as entrypoints to neighborhoods").

Connectivity and access as questions of usability in mobility planning. Some exemplars of mobility solutions that solve knotty problems of access and connection include:

-- public stairways such as the stairway connecting a neighborhood on a hill to the Weehawken waterfront in New Jersey

-- public escalators in Medellin, Colombia ("Medellín slum gets giant outdoor escalator," Telegraph) and Hong Kong

-- public elevators as part of the horizontal/vertical mobility system of "streets and blocks" in various places, including Monaco

-- funiculars and incline railways

-- aerial trams in Medellín, Colombia ("'Social urbanism' experiment breathes new life into Colombia's Medellin," Toronto Globe & Mail; "Medellín's 'social urbanism' a model for city transformation," Mail & Guardian), Portland, Oregon, Roosevelt Island, Queens, New York City, La Paz, Bolivia ("Largest urban cable car soars over 'desperate' commuters of La Paz ," Guardian

etc.

-- connections between communities such as Johannesburg's "Corridors of Freedom" ("A walk to freedom: can Joburg's bridges heal the urban scars of apartheid? ," Guardian) or the "Connective Corridor" between Syracuse University and the city's Downtown

La Paz cable car system. Martin Meija, Associated Press.

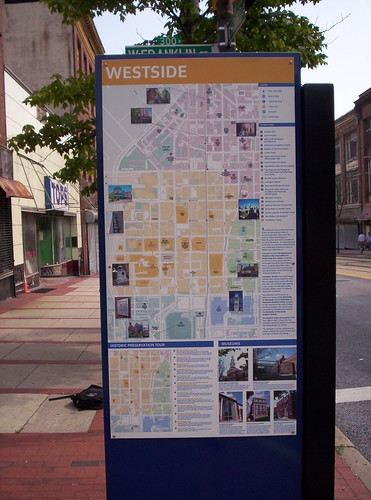

Wayfinding "monolith," City of Bath.

Wayfinding. Although they were writing about data management and interface design, in "Getting Lost: A Case Study in Interface Design," Elm and Woods make points relevant to wayfinding, that there are three different ways to be lost:

• Not knowing where to go next;

• Knowing where to go but not how to get there;

• Not knowing a current location in relation to an overall context.

Studies find that wayfinding systems have significant economic return, but some residents may resent the erection of wayfinding information in their communities, although having an integrated system that works at multiple scales is key to be able to place "a current location in relation to an overall context."

It turns out that the very comprehensive system created in Bath, England more than 10 years ago is the model for systems later deployed in London and New York City. The city continues to refine and extend the system, and has published recently a new set of strategic planning and design documents:

April 2020

New Link for Bath, use it to access the below cited documents

-- Creating the Canvas for Public Life in Bath: Public Realm and Movement Strategy for Bath City Centre

-- Pattern Book: Volume 01 Public Realm Framework

-- Pattern Book: Volume 02 Technical & Operational Guidance

-- Bath City Centre Lighting Strategy

-- Bath City Information System

The Legible London wayfinding system integrates pedestrian and bike share mapping, but the transit system, with its iconic mapping and signage, remains separate.

-- Yellow Book: A prototype wayfinding system for London, Legible London (Transport for London)

-- Legible London system architecture

In the DC-Maryland-Virginia region, three wayfinding programs stand out. Most recently, the City of Alexandria has implemented a comprehensive program that aims to move people from the Alexandria Metrorail station to the city's waterfront. While it includes signage at various civic facilities such as parks, there isn't a complementary rung in the system for neighborhoods.

Baltimore has a system covering the core of the city, including signage within districts. (Arlington County has gateway signs for various districts within the county, centered around Metrorail stations.)

Petersburg, Virginia has signage for its historic districts and downtowns, which includes neighborhood-scaled signage, but also a great deal of historic interpretation signage, as well as "color" coordination within districts (e.g., the Poplar Lawn Historic District is green, the Old Towne Historic District is maroon) and allied treatment of street and traffic signage.

Other communities such as DC or the Anacostia Trails Heritage Area in Prince George's County, have various wayfinding networks, although in the case of DC, they compete (e.g., history trails signage, Discover DC signage, National Park Service signage for the National Mall, a separate system for the US Capitol, etc.).

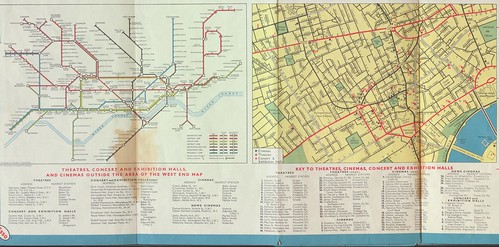

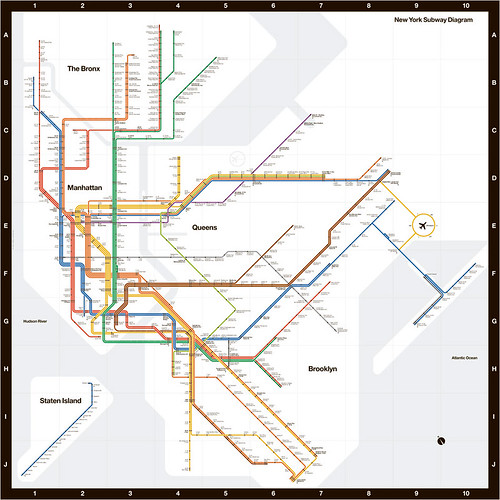

Overuse of the subway map concept as a way of representing information . The iconic subway map for London, based on the concept of an electrical circuit diagram, where the map is more conceptual and the transit lines don't map exactly to distance or topography, has influenced transit system mapping the world over.

Inset, London Underground and key sites in London's core, from a 1964 Esso gasoline station road map of London, UK.

For me, the problem with the approach is when it is applied, willy-nilly, to all kinds of other design problems, without regard to the nature of what is communicated.

The reason that a conceptual map works for transit is that the system of lines and stations is fixed. Once you enter the system through a station and then enter a train car, you travel a specific, fixed route, you can't deviate from the line (excepting transfers), until you arrive at your final destination.

Despite being lauded ("What if bike maps looked like subway maps?," CityLab), as a practical matter, applying the concept to bike routes doesn't work because they are just lines on a map that don't "map" to actual routes that a mobile cyclist must ride. Rather than sitting in a seat on a train, a bicyclist must actively cycle and navigate a real route. In such a situation, conceptual maps don't work.

Spider bicycle map for DC by Michael Graham.

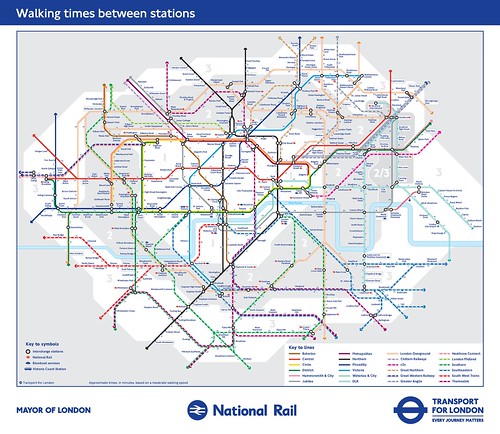

One wrinkle: walking between certain transit stations can be faster than transferring. In systems with many lines, a problem with subway maps not mapping to geography, but being a representation, is that people follow the maps literally, when the reality is that it can be faster to walk between certain stations, rather than going through the effort of transferring from one line to another.

In London and Singapore, the transit agency has created a walking map showing the distance between stations, while a guerrilla effort has produced a similar map for Toronto.

Walking tube map, London.

Interesting legibility/usability initiatives

Walk your city wayfinding. I think this was first done in Raleigh, NC, but was later written up in the Tactical Urbanism Manual.

-- Walk [Your City]

The Southwest Business Improvement District has used this idea to put up signage marking paths between the L'Enfant and Southwest Metrorail Stations and the new Wharf development on the Maine Avenue SW waterfront.

![Walk [Your City] style guerrilla street wayfinding signage produced by the SW DC Business Improvement District](https://farm5.staticflickr.com/4581/24421249988_4d5ba39a9d.jpg)

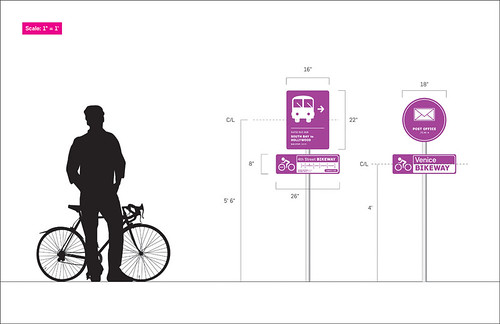

Better Bikeways Project. The project is a set of concepts by designer Joseph Pritchard to better distinguish bikeways and routes. According to Prichard:

Employing a simple yet comprehensive visual language, the Better Bikeways system is an attempt to communicate vital information and warnings to cyclists and motorists alike. The system was designed with the goals of easy legibility and comprehension in mind and is focused on four categories of information.

Navigation: Serves as the prime identifier of a bike route. It can also be used to offer valuable navigational information such as route destination and direction, and distances to major cross streets.

Caution: Conveys warning messages to motorists and cyclists. Because their message needs to be understood quickly and from a distance they are the largest and most basic of the route's signs.

Connections: Highlight intersections with other bicycle routes or public transportation hubs. Their goal is to integrate individual bikeways into a broader transportation network.

Points of Interest: Highlight points on or near the route of relevance to cyclists. By drawing attention to these locations, Point of Interest signs can help make bikeways more attractive recreational routes for cyclists.

-- "Better Bikeways: Getting Rolling with Improved Signage," GOOD Magazine

-- "Better Bikeways: Guerrilla Improvements and DIY Signage," GOOD Magazine

-- Better Bikeways

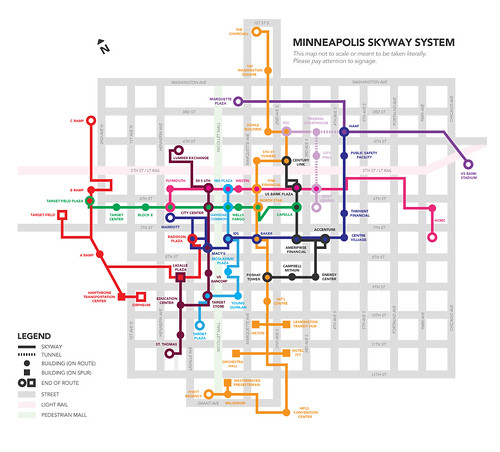

Remapping and re-signing the Minneapolis Skyway. While urbanists tend to prefer people on streets rather than connecting buildings through skywalks, underground and above-ground walking networks, such as Pedway in Chicago, PATH in Toronto, the Underground in Montreal, and the Skywalk network in Minneapolis are examples of important horizontal mobility systems in those communities.

In the City Pages article "Minneapolis' love hate relationship with the Skyway and how to make it suck a lot less," designer Brandon Hundt lays out an approach for remapping the Minneapolis Skyway system and a matching improvement program for the signage system.

While he doesn't realize it, it harkens back to the new London Tube map of the 1930s, although he references a similar map made much later in the 1970s for the New York City subway system, a map that ended up not being adopted. From the article:

The legendary Massimo Vignelli brilliantly took advantage of this in designing New York’s subway map. You’ll notice he completely ignored streets, distances, and curves, instead using straight horizontal and vertical lines, and the occasional 45-degree angle. Colors signified routes, and stations were equally spaced dots on the map.

Today we couldn’t imagine a subway system mapped any other way.

New Vignelli NYC subway map.

Let’s apply Vignelli’s principles to the skyway and its jagged edges. First, identify what matters to the skyway user.

1. Buildings, the skyway’s equivalent to a subway stop.

2. Skyways, the routes connecting the stops.

3. Destinations. The skyway walker doesn’t need to know north from south or east from west. (The city’s downtown grid runs northwest and southeast, anyway.) Instead, they should know they’re headed in the correct direction and getting closer to their intended location.

4. Distance. Skyway users are, for the most part, walking. This means we can’t completely ignore the concept of distance. While not needing to provide exact distances, we don’t want to be wildly wrong, either.

5. Streets. The skyway is in many ways an extension of, and connected to the street. Their blocks also form a good barometer of distance.

Map, Proposed redesign of the wayfinding system for the Minneapolis Skyway system, by Brandon Hundt

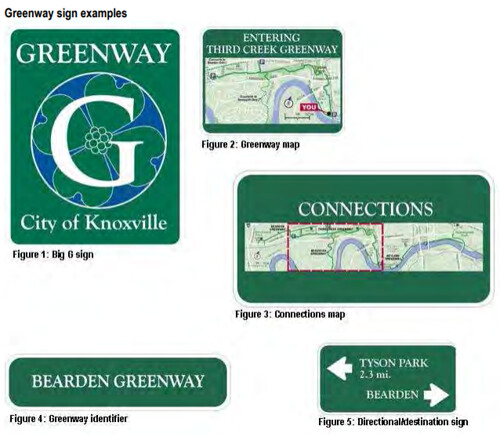

Knoxville Greenways and Blueways maps and signage. This is an official program, not a concept or a guerrilla initiative. It's a great model for other communities.

-- Knoxville Blueways

-- Knoxville Greenways and Trails

-- Knoxville Greenways Signage Guidelines, Knoxville Transportation Planning Organization

Labels: business process redesign, cartography and mapping, civic architecture, design method, graphic design, integrated public realm framework, transportation infrastructure, urban design/placemaking

6 Comments:

Absolutely fascinating, thanks.

One thing I've been pondering a lot in my walks -- and this isn't original -- is light.

Streetlights vs. lighting the sidewalks vs. lighting bikes.

None of which we do very well.

So I'd add that.

I'd add noise as well both good and bad.

https://www.wallpaper.com/design/jony-ive-apple-park

I wonder how he would design a city.

the piece was already so damn long, but I considered having a section on lighting.

The Bath plan that I linked to is pretty amazing, as it lays out where the night time economy is functioning and where they want to extend it. That only being one of the elements.

The international association LUCI has some great publications on this too.

I've written about it some

http://urbanplacesandspaces.blogspot.com/2014/01/night-time-safety-rethinking-lighting.html

This references the Eindhoven plan but I can't find it online

http://urbanplacesandspaces.blogspot.com/2014/06/lighting-as-element-of-urban-design-and.html

but... I haven't quite written about lighting as an element of the walking city to the same extent as I've written about what I am calling the "maintenance of way agenda" for the walking city ... which is more than merely snow removal.

When you think of that though in terms of dayparts, lighting is a big issue.

http://www.newscenter.philips.com/newsletters/lighting/eLuminous/2010/12/NL/downloads/city.people.light.book.pdf?origin=3_nl_nl_e-zine__li_dec_image15

I thought about going to testify about the proposed "Office of Night Life" to make that very point.

But it's not just about night life in terms of the entertainment economy, but the places we live, and safe routes between transit stations and stops, civic facilities like schools, rec centers, libraries, and parks, etc.

Whether we are talking about a sustainable city, an 18-24 hour city, a walking city, a biking city, a transit city, lighting matters.

noise. Yes. not so much from the "usability" standpoint, but yes.

That's why I think trolleybus networks can be great. They are so much quieter than traditionally powered buses.

A colleague shared this with me, but I haven't had time to delve into it:

https://theconversation.com/urban-noise-pollution-is-worst-in-poor-and-minority-neighborhoods-and-segregated-cities-81888

Hybrid buses are definitely an improvement. The ones I ride regularly still have a conventional internal combustion engine, and they don't shut off completely like most hybrid autos, but they run at or barely above idle. The acceleration from a stop is a lot quieter. Now, can we do something about all the shrieks and beeps? Especially the "kneeling bus" siren on most WMATA buses, far louder than other systems I use.

You’ll notice that the WMATA hybrid buses are properly being run and are being quieter.

The new circulator buses being run ARE not quieter. In anything more noisy than the Van Hool. They also stink as the engines are not tuned properly.

Same bus, same engine, different technician.

... Decades ago had a problem with a gas leak at the meter, which had been installed by contractors, not people working directly for WGL.

You make a very good point. It comes back to getting what you pay for.

====

I have a sound meter app on my phone, not that it is 100% accurate, I'll try to remember to do some sound testings on the buses.

Post a Comment

<< Home