Village Voice makes the point that signaling upgrades rather than the Second Avenue Subway would have made the most difference for problems on the Lexington Avenue Line (4/5/6)

While those of us into train-based transit are most likely always going to push for extensions of existing lines as well as new lines, the Village Voice points out that investments in signaling improvements on the 4/5/6 Lexington Line would have cost a lot less and had a lot more impact building the so far very truncated Second Avenue Subway.

While those of us into train-based transit are most likely always going to push for extensions of existing lines as well as new lines, the Village Voice points out that investments in signaling improvements on the 4/5/6 Lexington Line would have cost a lot less and had a lot more impact building the so far very truncated Second Avenue Subway.-- "Maybe We Didn't Need the Second Avenue Subway"

From the article:

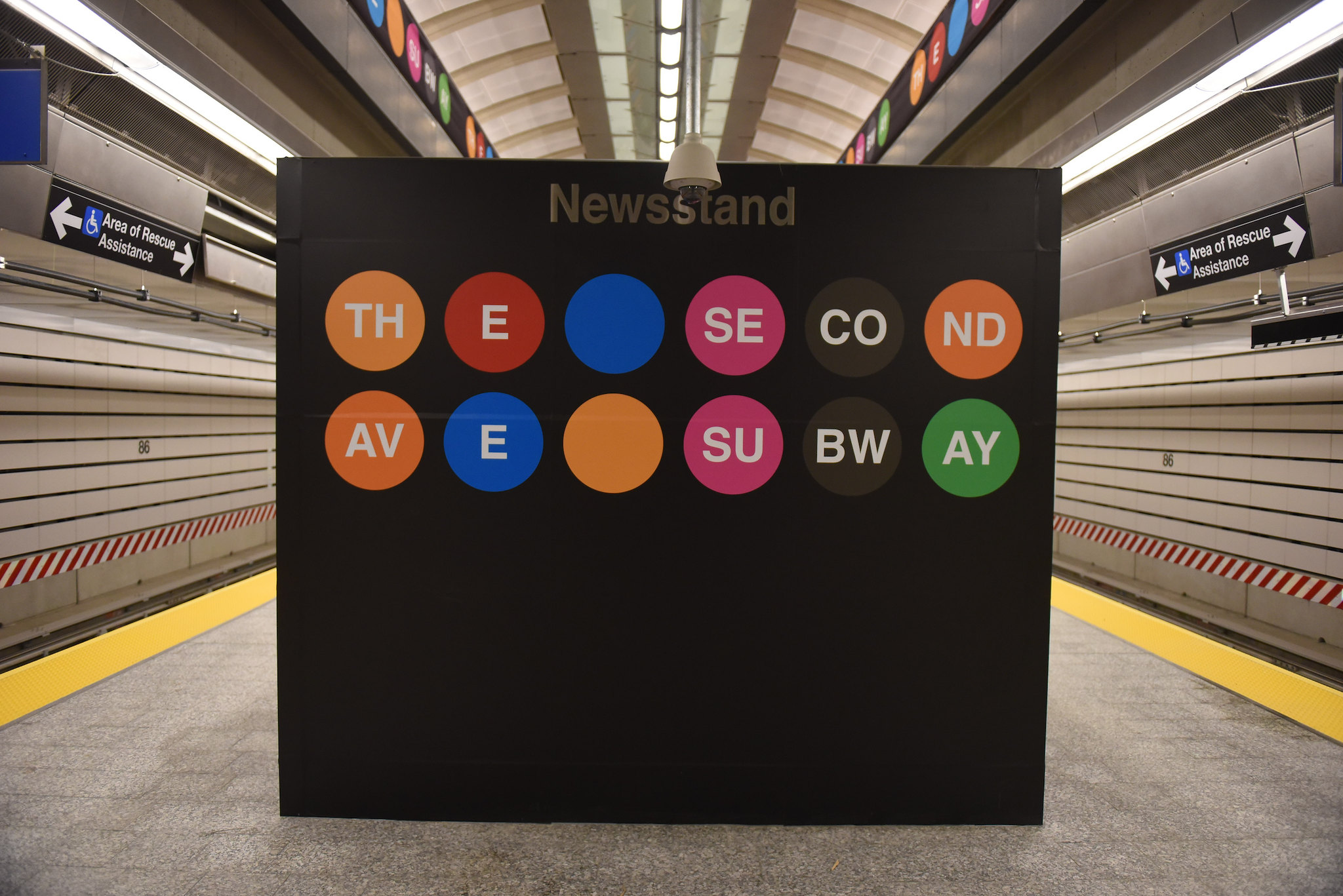

With last week’s release of station-by-station ridership figures for 2017, we can finally learn the impact this long-awaited subway extension had on the system. As it turns out, the Second Avenue Subway is undoubtedly a benefit, but at $4.5 billion for just the three stations built so far, a very expensive one. And the stats also tell us much more about the problem the line was built to solve — and raise the question of whether that $4.5 billion would have been better spent elsewhere.

The Second Avenue Subway’s primary reason for existence was to lighten the load on the overburdened 4/5/6 Lexington Avenue line, the busiest subway corridor in North America … This was a worthy goal, and to some degree, the new line accomplished this: The five Lexington Avenue stops closest to the subway extension — 96th Street, 86th Street, 77th Street, 68th Street–Hunter College, and Lexington Avenue–59th Street — saw 17,377,828 fewer swipes into those stations last year, or about 47,600 per day.

Meanwhile, the three new Second Avenue Subway stations experienced almost 21.7 million trips last year, or just a hair shy of 60,000 per day. After factoring in large ridership changes at other nearby stations — the Lexington Avenue–63th Street F/Q station saw a 1.3 million bump in trips, while the Fifth Avenue–59th Street N/R/W had 560,000 fewer — the total change in ridership after the Second Avenue line opened nets out to just a hair more than 5 million additional subway riders in 2017, or about 14,000 per day. …

We know now that the Second Avenue Subway could not possibly have been the most cost-effective way to relieve crowding on the Lexington Avenue line. That would be upgrading the signals to Communications-Based Train Control, or CBTC. One of the first lines Byford wants to tackle is, in fact, the 4/5/6 from 149th Street–Grand Concourse in the Bronx to Nevins Street in Brooklyn. Doing so would allow the MTA to run trains much more efficiently, increase capacity, and turn those ghost trains into real trains.

This project alone would provide a benefit to Lexington Avenue line orders of magnitude greater than the Second Avenue Subway for a fraction of the cost.While I don't always agree with the argument that it's better to forgo expansions and extensions in favor of "fixing what we have" because sometimes certain kinds of extensions and additions can improve throughput and network reliability as well as access (for example, this photograph of a c. 1989 NYC Subway map tells the story of a missing connection in the system, the need to connect one line the last 1500 feet to two othersy reduced throughput until the connection was made in 2001), this kind of question:

how to achieve maximum throughput?is the most important one to ask. And it needs to be answered in an objective way.

More generally, the argument for the Second Avenue Subway is reasonable, in terms of its full and complete eventual routing, which will serve other areas of the city that are underserved.

But in this case, construction of the Second Avenue Subway should have been pursued separately rather than positioning it as a congestion reduction measure for the Lexington Avenue Line.

=====

The problems with transit service in DC are different from Boston and different from NYC.

The problems in NYC are five fold:

1. An increase in demand

2. Antiquated signaling systems ("Meet the century-old technology that is causing your subway delays")

3. Old cars which are more likely to break down.

4. A decrease in operating speed for trains.

The last problem wasn't acknowledged by the system, until the Village Voice broke the story a few months ago ("The trains are slower because they slowed the trains down").

In each situation--DC, NYC, and Boston--what happened is that a system that had been at equilibrium experienced some sort of exogenous shock which exceeded the capacity of the equilibrium state to function normally.

With DC it was the failure to invest in maintenance and signaling problems leading to crashes combined with the Silver Line extension. With Boston--disinvestment combined with snowpocalypse. In NYC, increased ridership.

Labels: change-innovation-transformation, civil engineering, data and analysis, design method, transit infrastructure, transportation planning

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home