Reprinting with a slight update, "Arts, culture districts and revitalization" from 2009

"Arts, culture districts, and revitalization" is a reprint of a talk I gave at a national conference for the theater sector. But copying it from a Word document yielded weird formatting that I could never seem to fix. Plus, last year, I updated it slightly, adding one point ("Revisiting stories: cultural planning and the need for arts-based community development corporations as real estate operators").

Given that in an email back and forth I mentioned John Montgomery's paper, "Cultural Quarters as Mechanisms for Urban Regeneration. Part 1: Conceptualising Cultural Quarters," Saturday there was a "Made in DC" creative conference that I didn't know about and that the draft DC Cultural Plan has been moribund since last year's February 28th due date for comments, it's worth reprinting with the update.

=========

First published July 21st, 2009

My basic point is that real estate development interests have their own interests apart from artists, and that artists and arts organizations need to be conscious of what those interests are, harvest what they can from them, but never stop representing their own interests first and foremost.

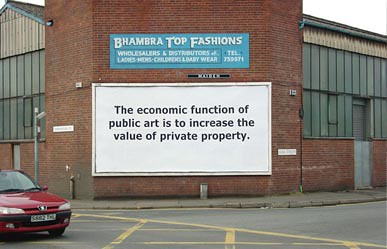

I am really sorry that I didn't come across this image before the talk.

The Economic Function, Billboard text at the corner of Corporation Street & Alma Street, Sheffield S3. 6 April - 20 April 2004. The work 'The economic function of public art is to increase the value of private property' sets out to question the function of art in the public realm within the economic regeneration of post industrial cities. The image will accompany a text in a journal by Public Art Forum to be published later this year. This work is the second part of a commission for Public Art Forum by Hewitt & Jordan.

There is some great academic writing on this issue. The sad thing is that it doesn't percolate down and get read by many people in the arts and revitalization field, although there are a number of papers published by the Social Impact of the Arts Project at Penn, some in association with The Reinvestment Fund, that discuss the issues and have a number of great citations to writings from academic journals.

-- Cultivating “Natural” Cultural Districts

-- Culture and Urban Revitalization: A Harvest Document

-- Creativity and Neighborhood Development: Strategies for Community Investment

Although there wasn't time to discuss the issues in great detail--we could have done an entire conference on the topic of "Theatre and Urban Renewal"--as a planner I did have some key points. This is the bulk of the paper (not all of it), but I spoke extemporaneously.

The intro was brief and didn't discuss the specifics of revitalization much at all. Note also that while arts and community building is important, and important to many people, it's not what I am personally interested in, and it is something different from economic revitalization.

This weekend we went to Artscape in Baltimore and the Station North Arts and Entertainment District there is a classic illustration of Montgomery's paper (below) as well as just about anything ever written by Jane Jacobs, in particular her point that vibrant cities need "a large stock of old buildings" because they have low running costs and therefore low rents and are available at low cost to support innovation and creative efforts.

For a long time, the area north of Penn Station and anchored by the Charles Theater complex was still pretty much bombed out... Now it might not show well, but it is amazing how it is starting to "fill in" between the cultural anchor of the Loads of Fun building at Howard Street and North Avenue and the Charles Theater. In between, along Charles Street and on North Avenue between Howard and Charles there are many "new" spaces that function as bar-restaurant and venues, a live music venue/bookstore, many independent and very small theater companies, of course bars and taverns.

This was part of the introduction to the paper, and the contrast between Baltimore and DC illustrates the points to a t...

-----------------------

Lacking the large stock of old buildings[1] that comes from having a manufacturing base which is the basis of bottom-up conditions that support artistic endeavors elsewhere, Washington DC is a textbook example of complications that arise from translating theory into on-the-ground reality, in a place where large and national-global arts institutions (Smithsonian Institution, Kennedy Center) dominate the cultural landscape, making it difficult to develop a thriving local arts scene.

Remembering that the impetus for developing an “arts district” tends to be driven by a desire to enhance real estate values, too often questions around how we develop, support and strengthen artists, creative organizations, artistic disciplines, and the creative economy are glossed over or under-considered throughout the various stages of the process of creating, developing and managing “arts districts.”

A big problem for artists is that the role of art and artists, their importance and relevance, may be secondary to institutional or real estate interests. This conflict is illustrated by the State of Maryland’s program of designated arts districts. Some are very much focused on entertainment and tourism, while others are more focused on building multi-faceted cultural production centers and contributing in significant ways to the development and furtherance of artistic practice.

Artist Mode of Production

Sharon Zukin in her study of SoHo in New York City[2], wrote about the “artist mode of production" where the arts and artists are used to convert (reproduce) low value (often abandoned industrial) property into high value commercial and residential property, and get displaced/priced out in the process.

The displacement effect is most likely to occur in places like DC and New York City, which are high value real estate markets.

In weak market cities like Pittsburgh or Baltimore, displacement is less of an issue because there are plenty of abandoned or underutilized low cost buildings available—although artists have other things to worry about—finding support and audiences, and remaining relevant are issues that matter to all of us, regardless of the size of our community or the strength of the real estate market, and especially the state of the economy.

Observations and Experiences in DC

DC has a successful local arts scene. The City of Washington spends millions of dollars supporting arts venues and organizations. At the same time, there is a high rate of organizational failure, and the ability to develop a wide and deep arts scene from the ground up is very difficult. Because the city’s identity is wrapped up in the story of the founding of the United States, it can be difficult to define and develop the local arts agenda separately from supporting large institutions [which are mostly national institutions controlled by the federal government such as the National Gallery of Art and the Smithsonian Institution], “National Myth” and what we might call “dead artists.” This comes at the expense of living artists, innovation, and the creation of new organizations.

Some of the things I have learned or am still trying to figure out, from working on urban revitalization in DC derive from the lack of a fully developed cultural infrastructure in the city [operating at the local scale]:

1. How communities support the development, maintenance, and type of cultural facilities and organizations matters. DC is ad-hoc. And the system generally is focused on supporting arts organizations, especially large institutions, not artists.

2. Arts organizations must represent their own interests but at the same time must look outwards towards best practices and bring that knowledge home. How can arts organizations ward off displacement as neighborhoods and districts improve?

3. There need to be more anchor organizations focused on supporting and developing artists, disciplines, and the creative impulse.

4. We need to leverage the power of the (creative) network.

5. At the same time how do cities protect their investments in arts organizations and facilities if problems occur with the owner-tenant-organization, and the municipality has invested in the organization and/or facilities?

6. How is the creative impulse, the ability of art and artists to challenge the status quo supported, not compromised? [Note this is still a problem, last year the DC Commission on the Arts and Humanities put out an artist call that forbade substantive criticism in art, although it was later rescinded. See "After outcry, D.C. commission backs down on censoring art," Washington Post].

7. Individual theaters compete against each other any one night, but the focus should be on generating audiences and repeat business -- people willing to come to a downtown or urban location need to be shared amongst the facilities, and that audience needs to be nurtured and expanded.

8. Community building [and arts education] is important but it isn’t economic revitalization.

Towards a Framework for Understanding Cultural Infrastructure

As a planner, I believe in plans and comprehensive frameworks, and believe that we can move forward by coming up with more complete ways of conceptualizing and addressing these issues.

Artists and organizations need plans and frameworks (both general and discipline specific) for understanding how the systems of cultural production and cultural consumption are conducted and to ensure that the right infrastructure is in place to support the creative impulse, arts production, and sustainable arts initiatives.

Cultural infrastructure is both hard and soft. The academic literature has tended to not differentiate between hard and soft infrastructure, but instead focuses on the definition of types of facilities, focusing on differences in type of space and programming. Instead, I argue that cultural infrastructure is comprised of at least five elements:

- Artists

- Place

- Space and facilities

- Cultural organizations and support networks

- Cultural-creative businesses;

Organizational failures should be seen as indicators of problems within the subsystems of cultural infrastructure

Furthermore, I would argue that failures, when they occur within the network of artists, arts organizations, facilities, and businesses, are indicators of weakness in one or more of these elements of cultural infrastructure.

-- "Cultural resources planning in DC: In the land of the blind, the one-eyed man is king," 2007

Instead of focusing on individual failures, although we grant that this often is an issue, we prefer to look at problems as part of the greater whole.

Cultural quarters/clusters

John Montgomery[3] discusses in great detail the necessary conditions and the factors that support the development of balanced cultural districts. A balanced district is a place for cultural production (making objects, goods, products, and providing services) as well as cultural consumption (people going to shows, visiting venues and galleries).

A cluster is a grouping of industries linked together through customer, supplier and other relationships enhancing competitive advantage. Over time the network of suppliers and organizations builds as organizations work together, and new businesses are created. Competitive clusters are characterized by organizations that are active in both local and non-local markets, and constant improvement and innovation. Montgomery calls this a production–distribution–consumption value chain.

Characteristics of cultural quarters (from Montgomery [2003] -- slightly revised and reordered)

1. Cultural venues at a variety of scales, including small and medium.

2. Availability of workspaces for artists and low-cost cultural producers.

3. Small-firm economic development in the cultural sectors.

4. Managed workspaces for office and studio users.

5. Location of arts development agencies and companies.

6. Arts and media training and education.

7. Art in the environment.

8. Community arts development initiatives.

9. Stable arts funding.

10. Identity, image development, branding and marketing support

11. Complementary day-time uses.

12. Complementary evening uses.

Six* things artists and arts organizations must do to represent their interests

(The original piece had five elements, this updates the list with the addition of the creation of an arts-focused community development corporation to buy, develop, and hold property.)

If we can agree that the characteristics enumerated above are the kinds of elements of a creative community that we want to achieve within our cities and sub-districts, then we have to figure out what pieces of the cultural infrastructure are missing within our communities and/or the arts and cultural districts and how to bring them about. There are many things that need to be done, but in the interest of time I will list the six that are most important.

The new list should be:

1. Create an arts-focused community development corporation to buy, hold, and develop arts properties operating at the scale of the city.

The biggest problem is that DC is a hyper strong real estate market with various conditions that make reproduction of space for higher priced uses inexorable.

While many efforts are focused on short term uses, the reality is that the local arts ecosystem requires a portfolio of permanently affordable space in order to thrive and maintain itself. Therefore, a mechanism for acquiring and holding arts-related spaces and facilities is required.

The best way to do this is through an arts-focused community development corporation. There are at least three such types. First, the multi-property large-scale initiatives of organizations such as the Pittsburgh Cultural Trust, Playhouse Square Foundation (Cleveland), the Brooklyn Academy of Music, and SEMAEST in Paris (the latter is more focused on providing retail spaces to creative endeavors rather than arts facilities).

Second, are multi-faceted cultural districts, usually managed by a coordinating organization comparable to a business improvement district (so over a geography smaller than the city], such as the Station North Arts District in Baltimore, and the aforementioned districts in Pittsburgh, Cleveland, and Brooklyn, as well as the Dallas Arts Public Improvement District. The smallish Penn Avenue Arts Initiative in Pittsburgh notably has facilitated the location of significant anchoring institutions such as the Pittsburgh Glass Center, the Kelly Strayhorn Theater, a 350-seat performance space, and the KST Alloy studios, two studio spaces suitable for rehearsals, classes, presentations, etc.

Third are one-off specific projects and facilities such as the Creative Alliance in the Highlandtown Arts District in Baltimore, which is housed in the former Patterson cinema building, various theater restoration efforts, projects by organizations which are members of the Nonprofit Centers Network, etc.

(While focused on the development of affordable artist housing, the Jubilee Housing Corporation of Baltimore is a premier example of a local CDC doing multiple quality artist-focused housing developments.)

-- "How the Arts Drove Pittsburgh's Revitalization," CityLab, on the Pittsburgh Cultural Trust.

2. Create discipline-specific cultural plans (as part of an overarching plan).

Many communities have cultural plans. Usually these are broad documents covering many issues including facilities, funding, disciplines, education, and community building. Some cities may have sub-plans within their cultural plan for facilities or public art. Seattle and Chicago are discussing the creation of framework plans to support the music industry within their communities.

But it appears that no city has developed what we might call a “theater plan.” Not New York City, where Broadway is central to the city’s identity and to tourism and where the theater industry is a key component of the region’s creative industry. Not Chicago, which is known for the most thriving theater scene between the coasts, ranging from neighborhood and repertory productions to “national” plays and musicals at Downtown theaters. The plans must be multifaceted, and address the needs of artists and cultural organizations, not just the economic or community building concerns of various constituencies. And, the plans must focus on matters concerning cultural production equally with the promotion of cultural consumption, arts-oriented tourism, etc.

Write a theater plan for your community.

[Examples to reference: Hamburg ["Tarzan' and 'Lion King' Make Hamburg a Theater City," New York Times]; Chicago; New York City; Branson, Missouri, although with a very specific family-friendly positioning.]

3. Come up with a sustainable cultural facilities plan serving the community, artists, and specific disciplines.

Part of your theater plan should include a sub-plan on facilities. Communities should develop holistic facilities plans that maximize use and revenues, and reduce overall costs, especially the demand for rent, so that arts organizations can achieve a relatively sustainable cost basis.

Washington, DC and nearby Arlington County in Virginia have two very different methods for supporting arts organizations. Arlington prefers to support a wide variety of organizations, and chooses to develop government-owned or controlled space in ways that support cultural initiatives in addition to other objectives. The County provides space (at low or no cost), access to a shared costume shop, and the use of a costume library to many theater organizations. The county has developed some facilities, including the Shirlington Library, which includes the Signature Theatre Company, and the Thomas Jefferson Middle School, which contains a large auditorium supporting a resident theater company and other productions, in ways that most communities do not. Arlington calls this approach their “Arts Incubator.”[4]

DC provides money to organizations for the acquisition or rehabilitation of facilities, but not in the context of a broader cultural plan focused on consensus priorities. In the past few years, many of the organizations that have received this support, including the Source Theater and the Lincoln Theater, have either ceased operations or have been pushed to the brink of financial solvency. In the broader cultural program, certain arts anchors have been pushed out of the city in favor of the baseball stadium, while other organizations, depending on their relationship with the Executive or Legislative Branches of Government, enjoy preferential earmarks. These grants are made without regard to a vetted set of priorities or through an open and competitive grant process.

4. Create anchoring institutions for the arts generally and disciplines specifically.

Artists, advocates, and organizations need to build their capacity to plan, organize, develop, and execute. Markusen and Johnson[5] found that the arts best contribute to regional economic and social development when there are “dedicated centers where artists can learn, network, get and give feedback, exhibit, perform, and share space and equipment.“

In their paper on creative infrastructure[6], the Creative City Network of Canada outlines six types of creative space, and four of the six: multi-use hubs; incubators; multi-sector convergence projects; and production habitats; are anchors, a set of either cross-disciplinary or discipline-specific facilities and programs that support the development of art, artists, partnerships, networking, connections, and cultural production.

Building the capacity of artists and organizations through these types of investment supports local economic and community building objectives, and improves the likelihood of success for all types of cultural initiatives. There are many examples of these types of facilities across North America (just not in DC) that serve as examples that you can consider for your own communities.

5. Networking with other disciplines to represent cultural interests at the scale of the community.

In addition to artistic centers and anchors—support and capacity development entities—arts organizations need to engage in some rethinking about how to work together to develop the arts community as a component of the community’s cultural infrastructure and as a force to represent artists and artist organizational interests in land use, capital investment, public finance, cultural, tourism, education, and other local policy matters, along with fundraising.

[Note: because this was focused on one discipline, I didn't mention overarching fundraising mechanisms. A number of communities have philanthropic initiatives that are quite interesting, especially Cincinnati. See "Funding arts and culture: ArtsWave, Cincinnati, 2018."]

6. Sharing Audiences between and across organizations

Another matter to consider is whether or not organizations can share and maximize the value of audiences within your community. Years ago I applied for a job at the Warner Theater, not knowing at the time it was owned by the big entertainment venue firm Live Nation. The Warner is one block from the National Theatre. In my cover letter, I made the point that while the theaters compete against each other at one level on any given night, at another level they share audiences amongst people willing to come Downtown to consume cultural events. (This was when going Downtown was seen as a risky adventure, when DC's reputation was somewhat unseemly.)

And that they need to do co-marketing and joint audience development. What best practice examples of arts marketing and membership can be adapted to your community, both for individual organizations as well as to build the success and identity of the theater community as a whole? Urban revitalization focuses on neighborhood improvement, usually through real estate-based strategies. Arts and culture strategies are particularly useful methods for reinvigorating otherwise ignored or abandoned places. But supporting and developing a place doesn’t always mean the support of arts, culture, artists, and the creative impulse in the manner that artists may prefer.

Conclusion

If we are to create balanced cultural quarters where new work is created, culture is maintained and developed, and the economy grows by reaping the value of production through the consumption of work in theaters, galleries, concert facilities and other venues, then artists and arts organizations are going to have to step up and better represent their interests in the context of a complicated economic, political, social, and creative environment.

By focusing on building a robust network of hard and soft cultural infrastructure, anchoring institutions and networking systems, in part through the development and implementation of discipline-specific culture and facilities plans, the theater community will be better placed to represent its financial and creative interests within the framework of broader community cultural planning.

Footnotes

[1] In Death and Life of the Great American City(1961), Jane Jacobs wrote that successful cities have four characteristics: density (which supports diversity); mixed uses; permeable spaces; and a large stock of old buildings to support innovative new uses.

[2] Zukin, Sharon. Loft Living: Culture and Capital in Urban Change. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1982

[3] Montgomery, J. “Cultural Quarters as Mechanisms for Urban Regeneration. Part 1: Conceptualising Cultural Quarter.” Planning, Practice & Research, Vol. 18, No. 4, pp. 293–306, November 2003

[4] Arts Incubator, Government Innovators Network, Harvard School of Government

[5] Artists’ Centers: Evolution and Impact on Careers, Neighborhoods and Economies. Project on Regional and Industrial Economics, Humphrey Institute of Public Affairs, University of Minnesota, February, 2006.

[6] Cultural Infrastructure: An Integral Component of Canadian Communities. Online document, 2009. Creative City Network of Canada, www.creativecity.ca

==========

Other relevant entries

Cultural quarters and innovation districts

-- discussion on the Arabianranta district within "Helsinki as an example of creative industries driving urban revitalization programs," Europe in Baltimore, 2013

-- discussion on the Liverpool Knowledge Quarter within "Liverpool regeneration as a process for regaining relevance at the regional, national, and global scales," Europe in Baltimore, 2014

-- "Naturally occurring innovation districts | Technology districts and the tech sector," 2014

CDCs and owning culture-related property

-- "The Howard and Lincoln Theatres: run them like the Pittsburgh Cultural Trust/Playhouse Square Cleveland model," 2012

-- "BTMFBA: the best way to ward off artist or retail displacement is to buy the building," 2016

-- "When BTMFBA isn't enough: keeping civic assets public through cy pres review," 2016

-- "BTMFBA revisited: nonprofits and facilities planning and acquisition," 2016

-- "BTMFBA: Artists and Los Angeles," 2017

Important elements often missed in creating city/county culture plans

-- "Should community culture master plans include elements on higher education arts programs?," 2016

-- "The song remains the same: DC's continued failures in cultural planning as evidenced by failures with Bohemian Caverns, Howard Theatre, Union Arts, Takoma Theatre...," 2016

-- "The tension between monetizing public space and placemaking | rethinking how neighborhoods are supported by local governments," 2018

-- "Leveraging music for cultural and economic development: part one, opera," 2017

-- "Leveraging music as cultural heritage for economic development: part two, popular music," 2017

Transformational Projects Action Planning

-- "Why can't the "Bilbao Effect" be reproduced? | Bilbao as an example of Transformational Projects Action Planning," 2017

-- "Downtown Edmonton cultural facilities development as an example of "Transformational Projects Action Planning," 2018

Labels: capital improvements planning, civic assets, comprehensive planning/Master Planning, cultural planning, government oversight, public finance and spending, public realm framework, urban design/placemaking

35 Comments:

Proposal for London Center of Music

https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2019/jan/21/twist-and-shout-is-this-the-tate-modern-for-classical-music-diller-scofidio-renfro-centre-for-music

London Culture Mile:

https://www.culturemile.london/

The developer is asking for a 22 foot height bonus for putting in a 4000 s.f. cinema building. There isn't discussion about rents, who will run the theater, etc.

https://www.bizjournals.com/washington/news/2019/04/02/developer-pitches-mixed-use-project-with-movie.html

The importance and support of regional theatre in the UK

https://www.thestage.co.uk/opinion/regional-theatre-is-the-bedrock-of-our-culture--without-it-we-bleed

6/3/2020

Renew Theaters is a nonprofit cinema/theater management organization in PA/NJ, which manages the operations of four separate theaters, each is its own separate nonprofit.

https://www.renewtheaters.org/

https://www.princeton.edu/news/2014/04/01/renew-theaters-will-operate-princeton-garden-theatre

Mentions the arts group AS220, an early arts organization in Providence, before the city began revitalizing.

https://www.bostonglobe.com/2021/08/19/metro/umberto-crenca-pays-homage-city-life-with-divine-providence/

Along the lines of Renew Theaters,

Groups of small nonprofits in Pittsburgh, in arts and environment-related groups, joined in and hired a CFO that serves them all. None could afford one individually, but collectively they can.

http://triblive.com/news/allegheny/7333326-74/nonprofits-arts-shared

+ Philadelphia has an organization that does the same kind of thing, providing back office and fiscal agent services, to nonprofits without necessarily having 501c3 certification.

https://www.cultureworksphila.org/

But other Philadelphia organizations do provide some fiscal agent services, I don't know about back office.

https://www.philaculturalfund.org/fiscal-sponsorship/

Howard County Community College is not renewing the lease for a theatre.

"Howard County’s Rep Stage is too important to lose"

https://www.washingtonpost.com/opinions/2023/02/12/howard-county-rep-stage-closure/

Regional theater is straining. Single Carrot Theatre is closing after 15 years. Last May, Olney Theatre revealed that it was on the edge. The Maryland General Assembly stepped up for Olney, but we need a longer-term, regional solution to keep theater strong. Rep Stage has brought thousands of people to the Howard Community College campus. Rep Stage has introduced hundreds of students to professional productions, many for the first time, working directly with theater professionals. Some have made theater their profession.

The letter writer, formerly director of the county arts council, says such facilities need to be saved. That's why you need a plan, a facilities plan, and a community development corporation to hold the properties.

Ann Arbor has a strong history of "student-run" film societies. Although such groups are maintained in part by the participation of alumni and community stakeholders.

This article is a review of a book about them. (I participated in one, Alternative Action Film Society.)

The review focuses more on the auteur and other elements.

I don't know about the book, but the review doesn't mention the importance of the availability of auditoriums/halls in various University of Michigan buildings, for relatively cheap prices.

That's what enabled the groups to develop and thrive. And it's a good example of the importance of the availability of usable spaces, in this case well located, for a good price.

'Cinema Ann Arbor' explores how U-M students created movie lover's dream

https://www.freep.com/story/entertainment/movies/julie-hinds/2023/06/18/book-explores-u-ms-history-as-ann-arbor-was-once-a-movie-mecca-thanks-to-offbeat-student-film-groups/70321287007/

Space for musicians and bands.

https://www.sltrib.com/news/2023/06/17/how-pillar-salt-lake-city-punk/

How a pillar of the Salt Lake City punk scene built a ‘needed’ space for artists

Space and Faders offers bands, podcasters, painters, poets and more rooms to rent out, and provides space for them to connect with other local artists.

That’s one reason why he felt the need to build Space and Faders, which currently has 14 practice rooms available to rent out — some monthly and some hourly.

At the center of the space is a lounge with couch seating, a couple of arcade games and walls littered with art and concert posters, where artists can meet and hang out with each other.

“How many guitar players hang out with a f---ing abstract painter?” Thorpe said. “But it’s very important for those people to know each other because their struggles are the same.”

Not every room is the same. The business provides some that are already set up so bands can just “plug in and play,” as well as empty rooms where people have to bring in their own gear.

There’s also a studio that can be rented out for podcasts, videography or photography. Still in the process of building the place, Thorpe has a vision for even more room options — which could include an editing workspace, a recording studio and other multi-purpose rooms.

ArtsAVL, Asheville, NC.

https://artsavl.org/

The arts council supports arts professionals and businesses in Buncombe Country through connection, advocacy and grants.

“The artist-run leadership model in the River Arts District has created a supportive and thriving home for artists, and in turn created a nationally recognized destination where visitors get the unique opportunity to see artists at work and view a vast variety of different artworks all in one location,” Cornell said.

Craig Setzer, a woodworker, specializes in furniture making and is a featured artist at Foundation Woodworks’ gallery and has worked in the attached woodworking studio for nearly a year.

“It’s such a mecca for artists,” he said. “It’s a pretty cool idea to have all these old, abandoned industrial buildings be turned into studios and artist sanctuaries.”

El Jaouhari said one thing that makes RAD unique is that the public can visit studios and witness the artists making their artwork. He said the city’s arts community widely ranges from technically trained fine artists to self-taught artists and crafters. Also, Asheville’s arts community extends from RAD to downtown.

Foundation Woodworks offers a shared woodworking studio designed to help woodworkers build their businesses by providing designated workstations for artists to rent. Setzer said the style of the studio is a rare find.

City development has aided in the sculpting of RAD, like the greenway along the French Broad River and new residential housing and businesses. The same elements that have supported the arts district have the potential to harm it.

This winter, ArtsAVL conducted a Creative Space Study in response to artists’ concerns about the rising cost of living. Cornell said local artists and arts businesses have expressed concerns about being priced out of the Asheville area. She said affordable living and workspaces are increasingly becoming more difficult to find, especially in areas like RAD.

Kerr said he’d like to see more single and larger studio availability, and he’s concerned that bringing more non-art-related businesses into the district will take space away from the local arts community. He said he’s witnessed that happen in Seattle and that it can change the culture of a city.

“My only worry is, moving into the future, that more places like that start opening means less places for artists to be. That could be a potential issue down the road, like you take the art out of the River Arts District it no longer becomes what it is known for,” Kerr said.

https://wlos.com/news/local/arts-avl-new-free-trolley-service-a-great-success-first-day-operation-partnership-gray-line-asheville-explore-north-carolina-arts-council-second-saturday-rad

https://avltoday.6amcity.com/education/artsavl-arts-for-schools-grant-now-open-for-applications

https://avltoday.6amcity.com/arts/artsavl-gives-an-update-on-ashevilles-creative-economy-at-the-state-of-the-arts-brunch

https://avltoday.6amcity.com/arts/buncombe-countys-creative-economy-bounces-back

https://artsavl.org/reports/

https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2024/mar/16/creatives-leaving-london-and-for-the-first-time-i-understand-why

Creatives are leaving London, and for the first time I understand why

Are young people, especially creatives, as excited about London, as driven to live in it, as people like me once were? The answer appears to be a very firm no, and, for the first time, I get it.

Yet another creative exodus appears to be under way, this time from London to Glasgow. Estate agents are reporting a significant spike in interest from Londoners. Prices have risen by 28% since 2019. Glasgow is a magnet for the alternative sensibility. Dynamic and artist friendly, the cost of living is 48% cheaper than London, with affordable property to rent and buy.

As one freelance curator and London-Glasgow migrant told the Times: “It feels like in London you have to be constantly running on this hamster wheel … In Glasgow, there’s more time to be creative.” Creatives getting the chance to be creative? Imagine that.

Together, squatting and dole-ocracy formed twin pillars of creative freedom, producing a vibrant subculture that arguably became the culture. However, in 2012, squatting in residential buildings (even empty, boarded-up ones) was made illegal. And, these days, people are forced off benefits into soul-sapping grunt work: sometimes several jobs just to survive (so much for all the glitzy-sounding guff about “portfolio careers”). Basically, they’re exhausted before anything else can happen.

When swathes of London became unaffordable, they quietly moved out to then unfashionable areas in east London. (Then out further, until they ended up in places like Hastings.) Everywhere they went in London, subsequent generations ended up priced out. The point being, once you start driving out such hardy, adaptable (masochist?) types in droves, you know the situation has become untenable, that the London game is up.

For generations like mine, living in London was an intrinsic part of the dream. Cities need these kinds of people in the mix. Creatives not only thrive in city culture, creatives make city culture thrive. It’s a symbiotic relationship going back centuries.

Now, London seems intent on exhausting, bankrupting and crushing its creative community, driving more and more people out. By doing so, it has finger-clicked awake a generation, broken an important spell. If London isn’t the foremost destination city, then what is it? Just a big dirty patchwork of overpriced boroughs? London has to get back to being more than just the capital – to being the great, sparkly, yellow brick road to the rest of your life.

https://www.cnn.com/travel/arts-district-las-vegas/index.html

Beyond the Las Vegas Strip, art is winning big

3/17/24

Visitors love Las Vegas for the glitz, glam and garishness of the resorts that line the 4.2-mile Las Vegas Strip, but the most exciting neighborhood in the city right now is all about art.

This area, fittingly called the Arts District, has become a haven for local creatives.

It’s a hotbed of culinary excellence, visual spectacle, digital design and immersive theater. It’s home to one of the city’s most popular restaurants, several cult-favorite bars and breweries, one-of-a-kind shopping and a boutique hotel. It’s even got the city’s only indoor half-pipe.

Evolution of a neighborhood

The Arts District was officially created in the late 1990s. Back then, it received the nickname 18b, owing to an 18-block area bounded by Hoover Avenue, Colorado Avenue, Las Vegas Boulevard, Commerce Street and 4th Street. Over time, the neighborhood has grown beyond these boundaries.

El Cortez Hotel & Casino: The El Cortez opened on East Fremont Street in 1941 as downtown Las Vegas’ first major resort and proudly promotes itself as the longest continuously operating casino in Las Vegas.

Today it loosely encompasses about 25 to 30 blocks (depending on whom you ask) south and west of Downtown.

In the beginning, the neighborhood revolved around a destination called The Arts Factory, a circa-1920s building that was repurposed to hold studios for more than 30 artists.

First Friday, a street fair and gallery crawl on the first Friday of every month, started in 2002 and was designed to get people into the area.

Gradually, in the 2010s, the Arts District started growing.

The first inflection point came in 2013 when sisters Christina and Pamela Dylag opened the Velveteen Rabbit, a laid-back cocktail bar on Main Street. Another came in 2016, when Derek Stonebarger opened ReBAR, a dive bar inside an antique store practically across the street.

The modern era began in 2018, when chef and Las Vegas native James Trees opened an Italian restaurant named after his great aunt: Esther’s Kitchen.

That’s when Trees decided to expand.

Instead of adding to the original location’s 58-seat dining room, he bought the circa-1943 Retro Vegas building on the corner of Main Street and California Avenue. The new $6 million digs, which opened March 8, seat 160 in the dining room and 27 at a standalone bar. The new kitchen is twice the size of the original restaurant.

Perhaps most importantly, Trees said that when dinner service ends around 11 p.m. every night, the new location will stay open with a limited menu until 2 a.m., a first for a restaurant in this part of the city.

“The new number of tables and [the new extended] hours aren’t to add more covers, we just want to allow people to actually be able to get a reservation, then come and spend more time and enjoy themselves,” he said.

All about passion

Esther’s Kitchen isn’t the only passion project in the Arts District; over the last few years, dozens of shops and other destinations have put down roots in the neighborhood, too.

Even veteran hospitality personalities are getting in on Arts District action.

Chef Wolfgang Puck is a co-owner of 1228 Main, a bistro that opened in July, and locals line up on weekends for pastries and loaves of freshly baked bread. The English Hotel, which opened in 2022, bears the name of celebrity chef Todd English.

Of course, art is still the main driving force behind everything in the neighborhood.

The Arts Factory remains the geographic and creative center, with artisans ranging from painters to jewelers keeping studios inside. Nearby, the “Greetings from Las Vegas” mural was painted in 2020, and it is now one of the most photographed destinations in the entire city.

Galleries span the gamut from cutting edge NFTs (the JRNY Gallery) to more conventional contemporary art (the Priscilla Fowler Fine Art Gallery). Geller Gallery, set to open on Commerce Street in March, specializes exclusively in imported art.

“Main Street is the new Downtown,” he said. “Las Vegas is small, so there aren’t other places that embrace weird art, creativity, uniqueness and individuality. It’s like we set ourselves up for this [Arts District] revival. I’m glad it’s becoming what it is now.”

Theater is alive and well in the Arts District, too.

The LaMarre Theater is the only free-standing theater in Las Vegas with Black owners and operators, and the Majestic Repertory Theatre continues to generate buzz for immersive performances that make the audience part of the show. The Cockroach Theater (yes, that’s really its name) is the second stage of the Vegas Theatre Company and spotlights emerging thespians.

Nightlife hot spots

The Arts District also has built a reputation for its eclectic nightlife—a scene that is more loungey, vibey and down-to-earth than the thumping and spendy nightclubs on the Strip.

Velveteen Rabbit and ReBAR were pioneers in this space, and subsequent additions such as Jammyland (with a Jamaican motif), Silver Stamp (with a robust beer menu), and Nightmare Café (a horror-themed cross-between TGI Fridays and Spirit Halloween) laid the groundwork for further innovation.

Also this summer, Nevada H&C Distilling, renowned for its Smoke Wagon Bourbon, was expected to open a new facility on the corner of Wyoming Avenue and Industrial Road. The new digs were expected to comprise an expansive production area, as well as a gift shop where visitors can purchase products and check in for tours.

On a longer timeline, the city has green-lighted the construction of more than 3,000 new living units in and around the Arts District — developments that most certainly will change the complexion of the neighborhood once again.

In a city that reinvents itself constantly, it’s good to know the next evolution will be inspired by art.

Not everyone wants to be an arts district

As the Warhol looks to branch out with Pop District, critics say it threatens museum’s mission

https://www.wesa.fm/arts-sports-culture/2023-12-18/warhol-pop-district-critics

Yet this free marketing class wasn’t run by a community college, say, or a local educational nonprofit. Rather, it was offered by The Andy Warhol Museum, as part of an ambitious initiative called The Pop District.

The District, which the museum launched in May 2022, is a $60 million, 10-year plan to remake the museum’s corner of the North Side with public art and a new performance venue. The initiative also includes workforce development programs.

The Warhol, one of the four Carnegie Museums of Pittsburgh, ranks among Pittsburgh’s top cultural institutions. Museum leaders tout the District as a model for cultural nonprofits seeking to improve their communities. Executive director Patrick Moore says the initiative is also a way to create new revenue for an institution that’s been operating in the red.

However, critics — including a number of high-level staffers who all left the museum recently within a year of each other — say the Pop District played a large role in their departure. They say the District threatens the 30-year-old museum’s mission as a keeper of Andy Warhol’s artistic legacy and promoter of cutting-edge art.

The Pop District takes that legacy as a jumping-off point. Named for Warhol’s indelible association with Pop Art, it embraces a four-block area. The Warhol said that the District will eventually create “over $100 million in annual economic activity,” spark $1 million in annual income for “creative talent,” and bring 50,000 or more new visitors to the North Shore each year. There is also a plan to site more public art in the immediate neighborhood.

Components include The Warhol Academy. The Academy encompasses both a Creative Entrepreneur Lab, to teach business skills to adults, and The Warhol Creative, in which young people are paid to learn digital content creation skills and produce materials for clients including the museum itself, Dell Computers and Howmet Aerospace. All the programs prioritize serving people underrepresented in the creative and technical industries, including people of color, LGBTQ+ folks, and women.

For now, the Pop District’s footprint is limited. Pop District logos adorn the storefront windows on a parking garage across the street from the museum. But the Warhol currently activates those spaces only intermittently, with events like youth screen printing workshops. Long-term, the District’s most prominent element might well be the planned $45 million events-and-concert venue, to occupy what’s now a surface parking lot.

Planning for the Pop District began in 2020, about three years after Patrick Moore was hired as executive director. (He replaced Eric Shiner, Sokolowski’s successor.)

Internal dissatisfaction at the museum seemed to crest starting in late 2021. That December, director of exhibitions Keny Marshall quit. He was followed by four other director-level staffers, including director of learning and public engagement Danielle Linzer (January 2022); senior director of external affairs Karen Lautanen (March 2022); chief curator José Carlos Diaz (June 2022), and chief curator Jessica Beck (October 2022).

The Pop District’s classes and workshops are outside the traditional function of an art museum, especially their focus on workforce development.

The Warhol Academy’s 20-week documentary filmmaking and social media fellowships operate as after-school programs four days a week in which students are paid $18 an hour to learn and to produce content.

In June, Citizens Financial Group committed $350,000 to the Pop District, both toward the Warhol Academy and to support the District’s biggest public art project to date, a mural by acclaimed Pittsburgh-based artist Mikael Owunna, installed on the side of a building across from the museum.

Then there’s the concert venue, known for now as the Pop District Entertainment Venue. The four-story building, clad in white, would fill the nearby “Brillo Box” parking lot with a 1,000-capacity concert hall to host touring bands and other acts. A 360-capacity event space would accommodate weddings, corporate gatherings and more for which the museum says there has long been far more demand than it can meet inside its current home.

Some former Warhol Museum staffers questioned whether the Pop District can achieve its lofty goals — in particular, in terms of job creation and new revenue.

“Those outcomes and the achievability of those outcomes, and what’s being done in the institution to try to achieve those outcomes, is directly responsible for why so many of us left,” said one former director.

"Anatomy of the Human," a mural depicting several large faces.

Bill O'Driscoll

/

90.5 WESA

Artist Mikael Owunna (with large scissors) at June's ribbon-cutting for his Pop District mural "Anatomy of the Human."

Moore says the museum can reach those goals — and, in fact, that it must. A big reason is that the Warhol is systemically underfunded. Its endowment — the pot of money nonprofits rely on for investment income and to stabilize their finances over time — is far too small. Moore said in April the Warhol’s endowment is “around $20 million,” but that “it should be closer to $50 million for a museum of this size and this reputation.”

For 2022, the most recent year for which a detailed breakdown is available, major sources of revenue included ticket sales, gift shop receipts and revenue from traveling exhibitions. Less than 40 percent was from gifts and grants.

But those touring exhibitions present a looming challenge. In 2022, according to the museum, they brought in about $850,000, or 13% of total revenue. Packages of Warhol works have traveled around the globe, from Brooklyn and Kentucky to Tokyo and Saudi Arabia. But like all physical objects, artworks suffer wear and damage in transit and on display.

“That’s why every year there’s a greater and greater number of objects that can’t be toured anymore,” Moore said. “Especially the very early work, and the iconic work, because it’s very fragile.”

So the museum anticipates a drop in this steady source of revenue.

Enter the Pop District Entertainment Venue. “The general goal would be to replace income from the touring program,” said Moore.

Warhol Museum associate director Dan Law, whose focus is the Pop District, has stated that one source of bookings for the venue would be touring musical acts that now bypass Pittsburgh.

Another piece of the revenue puzzle is the Warhol Academy. At the moment, the Pop District’s training programs rely heavily on philanthropy. Moore says the plan is to make the initiatives self-sustaining with revenue from clients of the museum’s in-house creative agency.

“That work as a content creation boutique agency basically, would over time hopefully scale so the Pop District could be sustained by that, the workforce elements of it,” he said. “But at the moment, we’re fortunate that we not only have it free for these young people, but they’re getting paid 18 dollars an hour to do the work.”

Good-Bye to All That: Boyle Heights, Hotbed of Gentrification Protests, Sees Galleries Depart

https://www.artnews.com/art-news/market/good-bye-boyle-heights-hotbed-gentrification-protests-sees-galleries-depart-10432/

6/8/18

BOOM Concepts celebrates 10 years as a hub for artists, community in Pittsburgh

https://triblive.com/aande/museums/boom-concepts-celebrates-10-years-as-a-hub-for-artists-community-in-pittsburgh

3/19/24

BOOM Concepts — a museum, artist incubator space, creative hub and community safe space that aims to build success through community and collaboration — celebrates its 10th anniversary this month.

Perry’s first solo show was at BOOM Concepts.

“They broke down how to put on a show, how to talk to people, the ins and outs of art shows, how even to hang art,” Perry said.

BOOM created its own in-house residency program in 2020. It also has a partnership with Radiant Hall Studios, where it hosts four artists. BOOM has a national partnership with Artist Communities Alliance and McKnight Artist Residencies consortium, which allows two to four artists to come to Pittsburgh from across the country to create public art, activist prints and murals. BOOM also partners with the Pittsburgh Cultural Trust and different outdoor markets.

Kinsel hopes that in the next 10 years, BOOM Concepts will be “able to help make some systemic changes in policy or status quo that critically affects artists’ ability to have a real-world career and be based in Pittsburgh,” Kinsel said.

They also have a studio at Kelly Strayhorn Theater’s Alloy Studios, where most of their out-of-town visitors come in to work.

All of the artists get free studio space and a stipend to work on and build on their projects.

“We do professional business development. We surveyed them about their goals and aspirations to see how we could help them out,” Agnew said.

Perry said that without BOOM, there may not be a Black Pittsburgh arts scene.

“They were doing it when it wasn’t trendy. BOOM was underground-ish back then and people just heard about it through the grapevine, and people now know it’s possible because of BOOM. They are the push for Pittsburgh Black art.”

BOOM is gearing up for the “Unblurred Take Over“ on April 5 from 5 p.m. to 8 p.m. They will partner with a few places along Penn Avenue that will host activities and exhibition work.

At Two Frays Brewery, two of their artists will exhibit in the restaurant, and a signature BOOM beer, which is still being crafted, will be on the menu.

“All the funds raised will go toward the bigger goals of our general operations and creating programs and really trying to get a forever home,” Agnew said.

Birmingham UK cutting all arts funding.

4 young artists on Birmingham’s devastating art cuts

https://www.dazeddigital.com/art-photography/article/62208/1/4-young-creatives-birmingham-devastating-art-cuts-100-per-cent-artists-austerity

Birmingham City Council – which effectively went bankrupt last year after a decade of austerity – has recently taken the dramatic step of cutting arts funding by 100 per cent and closing 25 of its 35 libraries. Going into effect next year, the decision is likely to have a significant impact on the city’s most prestigious cultural institutions, including its opera, ballet and symphony orchestra, as well as the Birmingham Repertory Theatre and the Ikon Gallery of Contemporary Art.

While Birmingham has reached a particular crisis point, culture funding across Britain is among the lowest in Europe, and many young artists in the city are already surviving without support from the state. But even among those who are unlikely to be directly affected by the looming cuts (and many will be), there are serious concerns about whether Birmingham’s cultural vitality will survive, whether the next generation of artists will be adequately supported, and whether more and more young people will be drawn towards the greater opportunities afforded in London.

The group developing a Black-oriented arts facility in Bronzeville wants public input

https://www.jsonline.com/story/money/real-estate/commercial/2023/06/27/bronzeville-center-for-the-arts-seeks-public-input-for-development/70360602007/

The nonprofit group developing a Black-oriented arts facility in Milwaukee's Bronzeville neighborhood is seeking public input on the project.

Bronzeville Center for the Arts will host its first public scoping session to gather community input to help determine future programming, exhibits and community space for its arts center.

The center bought the property from the state in 2022 for $1.6 million. The group plans to demolish it and build a 50,000-square-foot facility for exhibitions, education and immersive artistic programming.

Meanwhile, the center's 507 Gallery project is under construction and to be completed this fall. That 4,300-square-foot gallery, workshop and office will be at 507 W. North Ave.

Longstanding nonprofit arts properties CDC goes bankrupt in Toronto.

Artscape goes bankrupt. Organization owned property, was a developer, often in the US. I was critical because I said that the expertise in developing projects didn't stay local.

https://archive.ph/xahMJ

Artscape played a vital role in Toronto’s arts and culture communities. What happens now?

Richard Marsella is proud of the stars who got their start at the Regent Park School of Music — the opera singer, the poet, the jazz musician.

As executive director of the music school, housed in the Daniels Spectrum building in Regent Park, he has also seen how studying the arts benefits those who choose other professions, and how a group of arts organizations, brought together, can become something more than the sum of their parts.

“It’s like the connective tissue in a community,” says Marsella, of the building, which is home to arts and community organizations, art galleries and event spaces, and has become a neighbourhood hub.

https://archive.ph/FWcqp

Artscape formally enters receivership

The bankruptcy process begins as Artscape unveils more details about its restructuring plan, which will create a new affordable-housing non-profit group, called ANPHI Affordable Homes Inc., and a separate non-profit entity called ArtHubs Toronto Inc., which will take over operation of all community cultural hubs previously operated by Toronto Artscape Inc.

Artscape previously revealed that ArtHubs Toronto Inc. would use funding from the city and private donors to take over operations at Artscape’s community hubs, including Artscape Gibraltar Point on the Toronto Islands; its Regent Park community arts centre, Daniels Spectrum; and its Wychwood Barns facility, which hosts events and houses live-work studios and non-profit groups.

It also says new operating models are being developed for Sandbox, a multidisciplinary performance and event space in the city’s Entertainment District, and the community cultural hub at Weston Common. The city says it has exercised its option to buy Sandbox back “for a nominal price,” as part of its original agreement that transferred ownership of the property to Artscape.

=====

Artscape tried to launch a ‘game changer’ for artists. Then it found itself on the brink of collapse

After three decades of providing affordable living and studio space for artists in Toronto, Artscape set out to develop a new co-working and creative project called Launchpad. That’s when it all began to unravel

https://www.theglobeandmail.com/arts/article-artscape-launchpad-daniels-receivership/

11/10/23

Together with The Daniels Corp., a prominent developer that had recently partnered with Artscape on smaller projects, the non-profit announced a plan for something it called Artscape Daniels Launchpad, a new venue that would anchor a complex on Toronto’s waterfront. Artscape was getting into the co-working and incubator game, banking on the same optimism that many tech startups and venture firms had embraced in the 2010s. Financially, logistically and strategically, Launchpad was the most ambitious project Artscape had ever undertaken.

With Launchpad, artists would pay monthly membership fees to access shared spaces and high-cost tools they might need in order to become self-sufficient entrepreneurs, including recording studios and woodworking shops. It was to be a major departure from the non-profit’s many former projects, which had offered living and working space for artists in old, and later brand-new, buildings across Toronto.

The long-gestating project would eventually nab nearly $10-million in federal and provincial funding, and was supported unanimously by Artscape’s board, made up of Toronto developers, financial executives, city councillors, artists and artist-support workers.

“It will be a game changer for artists and designers,” Artscape’s then-chief executive, Tim Jones, said at the time. “A jolt of urban acupuncture that will help bring Toronto’s waterfront to life.”

Launchpad didn’t do any of that. In late August, 2023, suffocating under an unmanageable pile of debt – including $70,000-a-month payments to Toronto-Dominion Bank tied directly to the new facility – the organization revealed that it expected to be placed in receivership. It had fallen victim to its own ambition.

A Globe and Mail analysis, which included an examination of a decade of Artscape’s finances, found that Launchpad was the primary reason for the non-profit’s financial collapse. After Launchpad’s announcement, the cost of the project rose to $31-million, while the non-profit’s debt ballooned, more than doubling from $17.6-million at the end of 2017 to $37.5-million at the end of 2019.

======

Like Artisphere in Arlington. It's a losers game to expect to be revenue positive running an arts facility like this.

This is a great article on the failures.

Comments from the TGM article

- Launchpad was doomed to fail, they leverage way to much and there was funny business around the membership numbers

- before COVID there was about 250 paying member paying an average of $100/month. The rest were free bursaries sponsored by big donors.

- When Tim left and Grace started the latest Managing Director (number 5) came along and drove it even farther off the cliff.

- That 500 members quoted in the article would include free membership and the average price dropped to $30/month.

- The staff on the ground raised issues from the start

- The board should have never said yes to a pipe dream with no business plan. They were a team of yes people for Tim.

- Grace refused to acknowledge the toxic workplace and unrealistic business plan at Launchpad (business model was $1.5 to 2 million short every year)

- The leadership of Launchpad bullied the employees (all women and 80% IBPOC), we told Grace and she gaslighted us said it's not that bad.

- The new/old leadership at Artscape are to blame for this but Tim got a pay out and Grace is close to retirement so no harm no fowl for them, while their employees are let go with no warning or severance.

https://momus.ca/magical-market-thinking-reflecting-on-the-rise-and-fall-of-artscape/

Magical/Market Thinking: Reflecting on the Rise and Fall of Artscape

2/2/24

In discussions about cultural-space affordability, Artscape’s executives state their desire to overturn narratives of “artists as hapless victims of urban development,” preferring to refer to them as “agents of change” within their cities. Artscape’s claims of transformational economic self-sufficiency attracted governments (at all levels). But governments often repeat lofty proclamations about artists’ essential role in our cities while they lack the resources or political will to sufficiently support them. They are eager to embrace visions of cultural vitality without allocating the level of investment needed to achieve them. Their embrace of Artscape’s claims evidences magical thinking: that a “market-light” approach, one that mirrored the commercial real-estate market minus obscene profits, would solve the problem. On the heels of Artscape’s collapse, it’s important to understand how this magical thinking was deeply disconnected from the organizational, policy, and real-estate reality in which we all exist.

This was the enormous challenge that Artscape endeavored to take on: how do you provide affordability to a chronically underfunded sector within a profit-driven real-estate market? With its years of experience developing live-work spaces and its high profile, Artscape presented itself as “uniquely qualified” to tackle this dilemma, and its robust organizational capacity made it seem a safe bet to funders and developers. This outsize focus on capacity led to the consolidation of multiple cultural-infrastructure projects into Artscape. The organization became a behemoth that struggled to serve its artist-tenants and ultimately itself, begging larger philosophical questions: What does it mean for one organization to build up its own administrative and financial capacities on the backs of the cultural community it’s trying to support? Who benefits most from this top-heavy model? Is it the artists and organizations desperately in need of space, or is it Artscape?

Affordable spaces for art

Out of the hostile real-estate environment that has taken root in decades since, a new type of arts organization emerged: the nonprofit cultural-space provider. Unlike a typical market-based commercial landlord, a nonprofit cultural-space provider is mandated to provide secure and affordable space to serve the needs of cultural communities. These nonprofit organizations set out to deliver massive benefits to artists and cultural nonprofits by subsidizing rents, sharing resources, and offering secure long-term tenancies; in this vision, greater community cohesion would flourish among culture workers living and working in proximity. In Canada, Artscape was a progenitor of this new organizational typology.

Founded in 1986 as an initiative of the Toronto Arts Council, Artscape opened its first major project in 1991: Liberty Village at 60 Atlantic Avenue in Toronto, which housed forty-eight artist studios in more than 30,000 square feet. By the end of the 1990s, Artscape operated six different studio buildings around the city. It was, in its own words, based on a “social enterprise model, offering below-market rents that generated enough income for the project to be sustainable,” and to many in Toronto and around the world, it seemed a phenomenal success story. Through the 2000s and on the heels of Richard Florida’s “creative city” frenzy which urged cities to revitalize their centers by attracting the “creative class,” Artscape began to reframe its cultural-development activity as “creative placemaking,” a term it described as “intentionally leveraging art to act as a catalyst for community growth and change.”

By 2017, Artscape’s portfolio included twelve active sites and an increasingly complex organizational structure. The original nonprofit that served as the organization’s main entity grew to include a foundation to manage charitable activities (significantly, private donations), a housing nonprofit, an additional development nonprofit to manage their Daniel Spectrum project, and two separate corporations to handle its condo assets.

Imported vs. local solutions

As an Artscape affiliate, BC Artscape reflected its Toronto counterpart. The business model for the Artscapes, and for many other cultural-space providers, is intended to be one of “cost recovery” in order to keep rental rates as affordable as possible. The provider has a long-term lease with a private landowner or municipality, or (very rarely) owns its own building. The operator then subleases space to artists and cultural organizations at a rental rate necessary to cover the space’s operating costs, which often includes a head-lease rental rate, utilities, security, cleaning, staffing, building maintenance, and, in some cases, management fees. These hard costs and fees add up swiftly, and correspondingly, so do the rental fees needed to “recover” them.

Affordable to who

- most artists don't make much money

- most cultural organizations have small budgets

- hard to pay competitive wages

The Gap

Theoretically, these nonprofit cultural spaces are a way to address this financial quagmire by keeping rental costs low. But here’s the rub: The math does not actually work. In most cases, the total cost of operating these cultural spaces is significantly higher than what its target tenants can afford. At BC Artscape my colleagues and I began to refer to this harsh balance-sheet incongruity simply as “the gap.”

BCA joins with 221A

As an organization, 221A is currently working toward a Cultural Land Trust (CLT) for Vancouver. While still complicated by issues of scale, the CLT makes participatory governance structures, collective ownership of property assets, and equity key parts of its platform. A precedent for this type of organization can be seen in San Francisco’s Community Arts Stabilization Trust (CAST), which functions not only as an operator of nonprofit cultural spaces but also as a financial partner to support cultural organizations toward more self-determined ends. CAST works with its partners to build their financial and organizational capacities until they are able to purchase their own assets (which CAST has held in trust). Land-trust models like these prioritize building capacity across a community over the singular capacity of one organization.

Making Space for Arts and Culture

Vancouver Cultural Infrastructure Plan

https://vancouver.ca/files/cov/making-space-for-arts-and-culture.pdf

2019

https://thelocal.to/hot-docs-canadian-art-institutions/

Toronto’s Arts Institutions Are Crumbling and it’s Always the Same Story

The trouble at Hot Docs, TIFF, Artscape and the AGO are part of a larger failure in a country that doesn’t take art seriously

4/25/24

https://thelocal.to/spring-2024/

https://www.seattletimes.com/entertainment/music/seattles-royal-room-is-being-sold-here-are-the-new-owners-plans

Seattle’s Royal Room is being sold. Here are the new owner’s plans

12/21/24

When pianist and composer Wayne Horvitz opened the Royal Room in 2011 with Seattle venue owners Tia Matthies and Steve Freeborn, the team imagined a venue where musicians would call the shots, a home for “interesting projects” that didn’t necessarily fit the commercial mold. Thirteen years later, with thousands of shows under its belt, the ownership trio is selling its distinguished Columbia City gathering spot to Reese Tanimura, managing director of Northwest Folklife.

Tanimura, herself a musician, had spoken to the founding trio about entering into their partnership before the pandemic. When she reached out more recently to ask about taking over the entire endeavor, Horvitz said, “We were thrilled.”

Tanimura wanted to buy the single-floor, 99-seat venue at 5000 Rainier Ave. S. as part of her continued effort to expand access to Northwest arts, which began during a six-year stint on the Seattle Music Commission and has continued with Folklife. “I’m interested in how the city can provide a full spectrum of arts,” she said. “Art, economically and holistically, is so essential.” Tanimura curated a Womxn & Blues series at the Royal Room earlier this year before deciding to take the next step. She declined to disclose financial terms of the sale. Her ownership will begin in January.

Even after it changes hands, Tanimura says the Royal Room will remain a critical hub for the sort of wide-ranging, jazz-adjacent genres that Horvitz favors. Horvitz based some of his many projects out of the venue, including the 12- to 15- piece Royal Room Collective Music Ensemble and the similarly sized Electric Circus, which veers toward soul and rock. He hopes to maintain these projects and residencies, saying, “Now I’ll just talk to the booker like everybody else.”

The Royal Room will also continue to partner with the South Hudson Music Project, a nonprofit founded by Horvitz in 2016 to curate specialty music events and promote arts education at the venue. The SHMP was formed with sustainability and better staff working conditions in mind, two elements that Tanimura hopes to build out as she melds her values with the venue’s existing framework.

“Venues are an integral part of the creative ecosystem,” she said. “As a musician, it’s a challenging landscape right now. We’re all figuring it out. Anything we can do as artists ourselves to take agency with how we interact with the ecosystem, that’s great. For me, being able to helm a venue is a big responsibility. I feel really akin to artists and cultural workers. It’s a big opportunity to come together and serve the community.”

Five months in, Philadelphia’s TKTS booth promises a hopeful future for the city’s theater community

While some theaters are yet to see a big bump in sales through TKTS, they see the booth as a means to bolster the city's vibrant theater culture

https://www.inquirer.com/arts/tkts-booth-philadelphia-revenue-theater-tickets-20250422.html

"sharing audiences"

Through it, theatergoers can purchase same-day tickets for shows at up to 50% off. Based on recent ticket sales and Visitor Center website traffic, Soukup said the formula has proven to work in Philadelphia.

“They have been doing it for over 51 years in New York, and we’re just grateful to take both the brand and operational knowledge, and apply it to make something really special here in Philadelphia,” she said. “We look forward to it growing and amplifying over time.”

In Philadelphia, TKTS has partnered with 36 nonprofit arts organizations and theater groups, including Arden Theatre Company, 1812 Productions, EgoPo Classic Theater, and InterAct Theatre Company, among others.

Theaters can choose which shows, performances, seats, and ticket types they want to provide at a discount through TKTS.Through it, theatergoers can purchase same-day tickets for shows at up to 50% off. Based on recent ticket sales and Visitor Center website traffic, Soukup said the formula has proven to work in Philadelphia.

“They have been doing it for over 51 years in New York, and we’re just grateful to take both the brand and operational knowledge, and apply it to make something really special here in Philadelphia,” she said. “We look forward to it growing and amplifying over time.”

In Philadelphia, TKTS has partnered with 36 nonprofit arts organizations and theater groups, including Arden Theatre Company, 1812 Productions, EgoPo Classic Theater, and InterAct Theatre Company, among others.

Theaters can choose which shows, performances, seats, and ticket types they want to provide at a discount through TKTS.

Theater planning.

https://www.post-gazette.com/ae/theater-dance/2025/07/27/clo-pittsburgh-financial-crossroads-civic-light-opera/stories/202507230067

Pittsburgh's CLO at a major crossroads as it faces rising costs, increased competition

That mix is what separates the CLO — currently standing at both an existential and a financial crossroads — from the Steel City’s other main producer of Broadway shows, the Pittsburgh Cultural Trust.

While both organizations present a Broadway series at the Benedum Center each year, the CLO produces its own shows and incorporates local talent as a part of its mission. The storied Pittsburgh theater group has helped to kick off the careers of some now-famous actors, including Renée Elise Goldsberry and Zachary Quinto.

The Cultural Trust, which also has decades of Pittsburgh history in its books, presents Broadway touring productions that are created and packaged elsewhere and travel around the country.

One is growing, while the other has been forced to shrink its ambitions.

For some like the Pittsburgh Symphony, overall ticket revenue has actually increased, up about $750,000 this year over last, but even that hasn’t been fast enough to keep pace with costs, which include a 12.6% raise for musicians over three years. Pittsburgh Opera also reported small increases in the number of tickets sold and ticket revenue this past season over the previous season, but according to a spokesperson, “we continue to experience incremental cost increases from year to year, in areas such as personnel, materials and services. These costs do often increase faster than our ticket revenue.”

For others, stagnant or even declining sales in the face of increased costs are leading to reassessments and major adjustments to the business model.

The CLO has cut the number of shows it produces each summer from six to three and has also reduced staff.

... “We have to decide where does the art in our town that's made in our town sit versus touring productions, and what does it mean to be a city of makers versus importing talent?

“They both have a place, sure, but what do you gain as a community to have creatives living in your town that are teaching in high schools and teaching in colleges and helping build a creative economy?”

“One of the things that makes a CLO show special is that we have this mix of Broadway professionals who come in from New York City but also professionals in Pittsburgh and even emerging professionals, people who are just graduating CMU or Point Park or other schools,” Mr. Fleischer said.

“We always audition here first, then look elsewhere to fill the gaps.”

Market saturation

To top everything off, there are licensing challenges.

As the Pittsburgh Cultural Trust, the arts and real estate juggernaut that owns many of the Downtown theaters including the Benedum Center, has increased the number of Broadway touring shows it presents, that can leave fewer “hot” shows available for regional companies to produce.

Rights holders may choose not to release the rights for producing a show in a city or region if a tour is likely to come through for financial and strategic reasons.

So if the trust capitalizes on the success of the movie “Wicked” by presenting a touring version of the musical, that can leave organizations like the CLO out in the cold.

Youth theater

Where are Seattle’s stages for teen artists and leaders?

https://www.seattletimes.com/education-lab/where-are-seattles-stages-for-teens

8/14/25

Seattle has an incredibly rich arts ecosystem, but there are significant artistic and accessibility gaps in theater education. Some schools offer a robust array of performance opportunities; others do not have drama programs. Many students claw for the spotlight in adult-led, pay-to-play productions at youth theaters. Meanwhile, education departments at regional theaters often stick to school performances and the occasional workshop. Sure, these programs offer vital exposure to theater … for schools and families that can afford tickets/tuition. But they do not teach teens to collaborate and express themselves.

High schoolers are eager to create with their peers. It’s exhilarating and, perhaps more importantly, humbling. Imagine the best group project ever and the work is playing pretend. Young artists do not need fancy sets or costumes, but we need stages to tell our stories.

Seattle’s Teen Summer Musical celebrates milestone with ‘The Wiz’

https://www.seattletimes.com/entertainment/theater/seattles-teen-summer-musical-celebrates-milestone-with-the-wiz

Today, the Teen Summer Musical is a 10-week program that includes nine weeks of rehearsal — Monday through Friday, 9 to 5 — capped by a big weekend of performances.