Maglev as an opportunity for DC to underground through traffic on New York Avenue

Despite the existence of what are called "metropolitan planning organizations" which were created by the US Department of Transportation in association with local metropolitan areas, to coordinate transportation planning across jurisdictions in a metropolitan area and to some extent between metropolitan areas, this may not really happen if the MPO is relatively weak relative to other transportation agencies, or when borders cross state lines, etc.

Even different agencies within a state or local government may not coordinate very well or have such different agendas that they don't coordinate.

Dis-coordination. Not quite 20 years ago, a colleague Steve Pinkus used the term "dis-coordinated" to refer to how transit "works" in Baltimore, and I've never forgotten his use of that term.

Baltimore's problem is that it has one truncated subway line and one light rail line that mostly follows an old industrial railroad right of way. They have a couple lines, but not a network ("From the files: transit planning in Baltimore County").

For profit transportation firms aren't interested in playing well with others. Besides the example of how hard it is for passenger rail to co-exist with freight railroads, now that for profit entities are more involved in pushing new transportation technologies and modes things are even more complicated, because for profits focused on their mission have zero interest in working with others, unless there are marginal economic benefits to doing so.

Contributing in ways that make the entire transportation system work better is as they would say in the UK, "not in our remit."

I've been meaning to write about this in terms of a couple of examples. In Boston, The Federal Realty paid for a station on the Orange line to serve their development but it turns out that they didn't configure the station to be very accessible from the other side--the side where New Balance isn't, making it hard and expensive to open up that side of the station to other users ("Plans to connect Encore property with Orange Line move closer to reality," Boston Globe). From the article:

The Assembly Station was subsidized by Federal Realty Investment Trust, the main company behind the massive — and massively successful — Assembly Row development. So the station opens inward, next to Partners HealthCare’s new tower, and not to the riverside park on the other side of the tracks.And Brightline/Virgin Trains in South Florida, which I want to write about in another context in terms of promoting railroad passenger services, is expanding stations in a number of places in Dade County, but this then diminishes opportunities for the regional commuter railroad ("Amid Brightline's new flash, whither Tri-Rail?," Palm Beach Post; "Tri-Rail into downtown Miami awaits Brightline's action," Miami Today News).

Government may not work well with for profit competitors either. But governments aren't very good either at integrating the for profits into the transportation planning and operations mix either ("Another example of the need to reconfigure transpo planning and operations at the metropolitan scale: Boston is seizing dockless bike share bikes, which compete with their dock-based system"), at least in Boston.

German style transport associations bring all actors together. What I recommend is that regions create German style transport associations, bringing all the transportation operators and planners together in one body ("The answer is: Create a single multi-state/regional multi-modal transit planning, management, and operations authority association") so that coordination and integration can happen.

Maglev. This brings us to maglev in the Baltimore-Washington corridor.

While Governor Hogan of Maryland isn't particularly supportive of intro-metropolitan area transit, judging by his unwillingness to fund Metrorail in the DC area, grudging agreement to continue the Purple Line light rail project, but cancelling the Baltimore Red Line, and his general interest in promoting road projects, cutting tolls, etc., he is interested in Maglev ("Hogan calls maglev ride 'incredible,' says state will seek $28 million grant to study," Baltimore Sun).

The Northeast Maglev company is aiming to create a Maglev system in the Northeast and they've got Gov. Hogan on board to start with a segment between Baltimore and Washington.

The study for federal approval is underway ("Federal review of Baltimore-Washington high-speed maglev project ‘paused’," Washington Post). Recent media reporting has focused on growing opposition ("Maryland towns gear up to fight proposed high-speed train," WP).

Could a double stack tunnel be used for maglev and freeway through traffic on New York Avenue? But the first thing I thought of when I read the article on the postponement of the federal study, and the mentioning of how the main station for the line in Washington, DC would be in the Mount Vernon area, meaning the line would come through DC under New York Avenue (which connects to the BWI Parkway, where the line would run underneath), was how the initial recommendation in the c. 2006 DC Department of Transportation New York Avenue Corridor Study for the "undergrounding" of how New York Avenue in DC connects I-95 in Maryland to I-395/I-95 in Virginia could be realized through a doublestack tunnel for the maglev trains and the freeway.

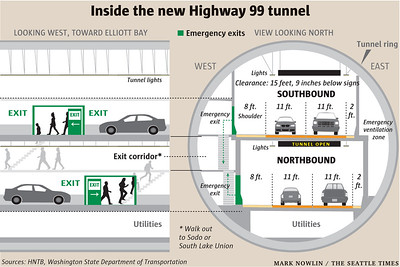

The Highway 99 Tunnel in Seattle is double stacked, with northbound traffic on one level and southbound traffic on the other.

Many years ago, concerning the Silver Line Metrorail in Northern Virginia, advocates proposed a double stack tunnel configuration which could have supported express services.

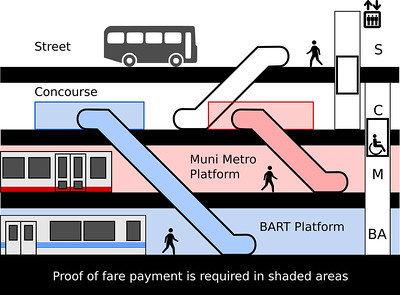

In Downtown San Francisco, the Muni Metro and BART run in a double stack tunnel called the Market Street Subway.

I am not an engineer. I don't know if the requirements for maglev and vibrations make such a double stack tunnel proposal out of reach.

Yes it would be expensive. But it would probably be cheaper to do "two projects in one" rather than either or neither.

Too rarely, big projects position themselves around complementary benefits. But separately, were I running the project, to ward off opposition, I'd be discussing benefits to the existing residents from the project.

While we can tout benefits from being at the forefront of implementing new transportation technologies, that doesn't really add much value to the lives of average citizens.

But tunneling through traffic for New York Avenue in DC, and similarly, using the Maglev project in Maryland as a way to drive forward comparable improvements to the BWI Parkway ("Hogan wants Maryland to take over Baltimore-Washington Parkway," Sun) ought to be seen as big benefits for those respective communities.

But unfortunately, our planning system now doesn't aim to leverage and create such opportunities.

Labels: metropolitan planning organizations, transportation planning, urban design/placemaking

8 Comments:

Why would we want to encourage more high speed traffic along NY Ave? Particularly at such great cost? How does that help us meet city's climate and transportation goals?

I knew I could count on you to respond.

In my writings, I argue there are three types of traffic:

- to/from a place

- within a place

- through a place on the way to somewhere else

A lot of freeway traffic is the third kind.

The NY Corridor study focused on the negative elements of the "through traffic" between Maryland and Virginia and how NY Avenue acts as a connection between I-95/Route 50/BWI Parkway and I-395.

Although NY Avenue also has a significant amount of commuter traffic from Maryland which is equally significant and should be diverted from the surface if at all possible.*

The impact of this traffic on the quality of life and aesthetic conditions along the New York Avenue corridor is pretty negative.

Dave Thomas Circle is but one example. But certainly the area between N. Capitol and the I-395 entrance/exit, even to 6th St. is pretty grim. The area over the railyards. Between the Brentwood Parkway and the Bladensburg Raod, from Bladensburg Road to the State Line.

It's all pretty s****y. That wasn't the word used to describe the conditions in the NY Avenue Corridor Study though.

So can the city really decrease through traffic when it has almost no way to influence it?

Should we not be concerned environmentally, to improve the quality of the environment, air quality, etc., at the surface. Let alone aesthetic (urban design) considerations that can improve the economic development opportunities along the corridor.

... and I didn't even think about underground opportunities for VRE storage, although with bi-directional service by 2030, that goes off the table I suppose.

Plus the high speed traffic wouldn't be along the current NY Ave. It would be under it.

And the above ground part could be redeveloped as a boulevard with a lot less traffic that is "regional" in nature.

It'd have to be tolled. But despite the fee, most people would probably prefer it.

And speaking of AQ, you'd get huge reductions in emissions, particulates etc. at the Bladensburg, Montana Avenue, Florida Avenue, North Capitol, and I-395 intersections. I'd love to see that modeled.

* I've argued in many places that DC should take every opportunity to underground/divert commuter traffic on various routes like North Capitol and Blair Road and New York Avenue especially, but in the case of this and I-695 and DC 295 through traffic too, to improve quality of life on the surface streets, for the abutting neighborhoods.

Some European cities have done this with waterfront roads, downtown roads, etc.

Obviously, although it was not necessarily an easy job, an example is the Big Dig in Boston.

There are examples, here and there of freeway decking.

It might be better to say, New York Avenue functions as an extension of I-95 from Maryland connecting to I-395 and ultimately I-395/I-95 in Virginia.

"So can the city really decrease through traffic when it has almost no way to influence it?"

This assumption (that the city has no influence) is completely wrong. The City has tons of ways to reduce through-traffic. They likely don't want to use them, but they can do it. The solution is obvious - just slow things down, reduce capacity, etc.

In simple terms, if you take space away from traffic and cars, then you'll get less traffic and cars.

What's also clear from the Big Dig and the Seattle tunnel is that they haven't reduced traffic or congestion at all; they've just moved things around at tremendous expense.

If you want a very expensive tunnel to encourage through traffic, that's certainly a choice to make. But again: why are you assuming that is what the city wants?

Why put the high speed traffic underground (at great expense) when you could just eliminate it entirely?

If maglev is going to be built, they'll be building a tunnel. Which is the whole reason for the post. It's a lot cheaper to build a tunnel if someone else is going to be doing it anyway.

2. I don't agree that the city has the ability to divert the traffic.

Sure, I guess you could make it go around the city, via the Beltway and Wilson Bridge. But traffic is like water, it flows to the area of greatest efficiency.

How would you divert the traffic?

Because yes, if it didn't exist, you wouldn't need the tunnel.

Traffic is not like water! Traffic is like a gas - it will expand to occupy whatever volume you give it.

If traffic behaved like water, we wouldn't have the examples of traffic just disappearing when various roads are removed.

Even if you wanted to build the tunnel, I doubt that this project would offer any efficiencies in doing so. The geometric requirements for a maglev moving at 300 mph and those for a roadway are so incredibly different that there's little benefit to combining the tunnel projects.

It's not at all clear that two projects combined would be cheaper. For one, the scale would have to be massive - the Seattle tunnel already used a world-record size TBM and that's just for two lanes in each direction - you'd need that size just for the roadway if you wanted to meaningfully bury NY Ave and that means the Maglev would be a separate, conflicting project.

As for ways to divert the traffic:

1. Tolls

2. Constrain the roads. Design NY Ave not to move cars, but to favor people. This would also make the land next to NY Ave much more useful. Add bus lanes to increase people capacity.

3. Design for lower speeds - work specifically to increase the travel time for through traffic. This would have the benefits of a) dramatically improving conditions along NY Ave while b) discouraging through-traffic from using the route.

This might be one of those cases where I am the one who lacks vision or belief that this could be done.

This column by Gaby Hinsliff in the Guardian, using Oslo as the example, is more visionary, based on the kind of thinking you outline:

https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2020/jan/14/driving-city-clean-air-zones-birmingham

The idea that traffic should just disappear is just a re-labeling of the traditional DC racism of refusing to build any extension from the I-395, with the push to push the traffic burden disproportionately through SE/Anacostia.

The Ron Linton plan for such an extension of geometrically deficient. The proper extension - not seen in any official planning documents - is for an O Street Tunnel; see December 2007 A Trip Within The Beltway at blogspot.

The idea of placing the maglev to Mount Vernon Square is likely significantly more expensive than Union Station, so why is it even being considered?

Post a Comment

<< Home