Shareable pogo sticks: an indicator that micromobility has "jumped the shark" | Pedestrian Road Design/Signature Streets

Jumping the shark is a term invented by Hollywood to describe a moment in a tv show that indicates the show is on its downward spiral and soon to be cancelled. There was a Happy Days episode where Fonzie was waterskiing? and he jumped over a shark.

Micromobility is the term coined to describe/re-term "new" and old modes that support transit and are sustainable but "individually operated" including bicycling; dockless shared bicycles; dock-based bicycle sharing; electric bicycles; scooters both stand up and sit down; wheels and hoverboards; skateboards; and now pogo sticks.

-- THE MICRO-MOBILITY REVOLUTION: THE INTRODUCTION AND ADOPTION OF ELECTRIC SCOOTERS IN THE UNITED STATES, Populous

While I rue that to most people, bicycles are toys, the fact is that pogo sticks are toys, and shouldn't be considered a realistic and practical transportation mode.

But that doesn't stop "visionaries" and the sloshing around of capital able to fund them.

AFP photo.

AFP photo.According to Local France ("Dockless pogo sticks could be joining scooters on streets of Paris"), shareable pogo sticks are going to be introduced in Malmo and Stockholm, Sweden later this summer, and the founders are looking to Paris for their first deployment outside of Sweden.

From the article:

Swedish tech start-up Cangaroo has announced that it will be launching a fleet of shared, app-based pogo sticks in Malmo and Stockholm this summer.It seems a misnomer to call this a fleet. Yes, there are a bunch of toys that people can rent. But even grouped together, they don't rise to the level of what we would term "a mode of transportation."

=======

Expanding micromobility options does increase vulnerability in the roadway network

One of my lines is that the point of planning is to "design conflict out" rather than to "design conflict in" to the system. E.g., pedestrians walk about 3 mph, so mixing pedestrians with faster vehicles is problematic.

One of the problems posed by micro-modes with "small points of contact" to the surfaces on which they travel--for example, the wheels of a bicycle are much larger than the wheels of a standup scooter--is that they are much more vulnerable to defects in the quality of the surface, especially when combined with the faster speed of electrically powered modes like scooters and e-bikes, which reduces the time to act when faced with complications.

World Resources Institute argues ("Scooter Use Skyrocketing in Cities, But Are They Safe? A Look at the Evidence") that this means that local government agencies need to upgrade the quality of roadways and sidewalks. For example, they write this in response to a study of e-scooter related injuries in Austin, Texas:

… given that 55% of riders were injured on the road, and 50% of interviewed riders believed that pavement surface conditions led to their injuries, it would be useful to conduct analysis of road design, quality and maintenance. It would be interesting, for example, to analyze the relationship between injury locations and infrastructure for riders, such as bike lanes and other design features. A quick visualization of injuries reported in the study overlaid with the city of Austin’s own database on “high comfort” bike infrastructure is a starting point. Most injuries occurred away from protected infrastructure.While there is no question that cities need more and better micromobility infrastructure, I think it's both unreasonable and unrealistic to expect that roadway and sidewalk pavement quality can be maintained at the level of quality necessary to support "fast" devices with small point of contact "devices" in all situations.

As it is there are plenty of pavement issues when it comes to biking, and bikes are far more versatile at dealing with pavement imperfections.

Yes, pavements should be free of holes and gaps and cracks, but to expect pavements to always be perfect enough for scooters or pogo sticks is a standard of quality/service that is unlikely to be able to be met, let alone maintained.

WRI goes on to make broader points about road design as it relates to modes other than the automobile:

These studies might provide insights on potential scooter design pitfalls or riding at unsafe speeds, which are important safety elements. However, as scooter use grows, city leaders should consider a risk factor external to riders’ control: the way our roads are designed.

Over the last decade, the number of people struck and killed while walking increased by 35%, while vehicle miles traveled grew steadily. Drivers killed more pedestrians in the United States in 2016 and 2017 than any other year since 1990, and, globally, the numbers are also getting worse.This point is reasonable. Roads are primarily designed for cars, even in cities where take up of non-automobile modes is considerable.

I just don't think that positioning this general argument using scooters (or pogo sticks for that matter) will help us make much headway.

I just don't think that positioning this general argument using scooters (or pogo sticks for that matter) will help us make much headway.Similarly, sometimes bicyclists try to make the argument that bicycling should be supported because the "quality roads" movement was initiated by bicyclists, before cars even existed.

But that argument carries little weight with automobilists. It's a waste of time to try to position the argument that way.

Note that I did write about these issues in the entry "Pedestrian fatalities and street design" in March, and separately my "Signature Streets" concept is all about how to position roadway and roadside characteristics for sustainable modes as well as cars, in a manner in which motor vehicle operators are more likely to support the argument.

Signature Streets concept

At the tail end of the development process for the Western County Pedestrian and Bicycle Access Plan, I came up with a concept that I called "Signature Streets" but with less than 10 days to wrap up the project and plan document, I didn't have the time to develop the concept more thoroughly to be able to "sell" it adequately to the advisory committee.

The basic idea was built upon the realization that the set of primary arterials in a community is the foundation of its mobility network and the aesthetic qualities, positive or negative, shape the perceptions of the community.

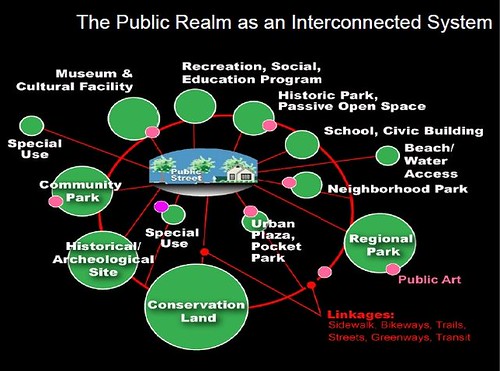

Since 2010, I have extended these concepts expanding outward from transportation and call it the integrated public realm framework (from David Barth) or the network of civic assets (civic assets network), and recommend that we do integrated and comprehensive planning around public assets as an coordinated system of related and inter-connected facilities, sites, and programs.

This argument has been developed across a number of posts, including:

-- Transit, stations, and placemaking: stations as entrypoints into neighborhoods

-- Public buildings as vehicles for community improvement (continued)

-- A clustering approach to the management of civic assets

-- Civic assets and mixed use

-- The Central Library planning process in DC as another example of gaming the capital improvements planning and budgeting process

-- Another take on municipal capital improvement planning

-- Provision of public services and recreation centers

-- Town-City Management: We are all asset managers now

-- An example of using variegated road material treatments in Bothell, Washington

Rockville Pike, Montgomery County, Maryland.

Designs for most arterials do not prioritize aesthetic or place considerations. Note that the "parkway" road type, typical of the 1920s and 1930s is an exception.

The challenge is to balance mobility, commercial, and aesthetic-place priorities in street design, in a land use and transportation planning paradigm that focuses mostly on prioritizing the throughput of automobiles.

Right now I think we can all agree that almost without exception, principal arterials, oriented to facilitating automobile traffic and throughput, are pretty grim places.

Recognizing the privileged position of the automobile, why not acknowledge and address the fact that the road network becomes the primary shaper of a community's identity by enhancing the aesthetic qualities of the road network, and by expanding the mobility qualities of the road network to incorporate sustainable modes.

The key concepts are:

(1) combine complete streets principles and the concept of defining roadway characteristics, roadside characteristics, and desired operating speed of traffic according to land use context as discussed in the Smart Transportation Guidebook

(2) with smart growth ideas focusing on inward investment on existing places rather than growing and expanding ever outward

(3) along with the integrated public realm concepts of David Barth

(4) by designating a subset of a community's road network as foundational or "signature"

(5) and upgrading these streets with systematic special and complete treatment so that sustainable transportation modes (walking, biking, transit, etc.) are integrated into the mobility system (also related is Barth's concept that streets should be treated as linear parks), along with streetscape improvements (it happens that Baltimore County already has an excellent streetscape improvement program, just not a focus on sustainable transportation) so that the streets also are a means for strengthening quality of life and "placemaking" for neighborhoods and districts they serve most directly

This rebuilt section of Virginia Avenue SE includes a cycletrack and new brick sidewalk.

(6) while incorporating branding and identity systems within the transportation network and the broader network of civic assets in part as a marketing tool

(7) with all of these elements in combination to support the case for financing using bonds and winning the vote in favor of the bond referendum, therefore raising the funds to pay for the development and enhancement of the upgraded mobility network and acquisition of the necessary right of way.

Unfortunately, my concept for an integrated signage system for county civic assets and facilities didn't go over too well either. But I attribute that to not having enough time to work through a couple iterations of the concept, to get to a point where people would have become more comfortable with such an approach. Graphic design concept by Tim Hampton.

In most communities (not DC), to expand the right of way, you have to buy the land. That's expensive. The government doesn't want to do it.

But by positioning "Signature Streets" in terms of making the road system better by adding elements that build a more complete mobility network that enhances quality of life and how the county "deserves" a road-mobility system meeting 21st Century needs, and in keeping with the fact that the County is the third largest jurisdiction in the State of Maryland makes this kind of re-thinking achievable.

Looking north along Bothell Way Northeast’s “multiway” boulevard in downtown Bothell. The “multiway” boulevard shows faster traffic and a separated lane used for parking, bicycles and business entrances. Photo: Steve Ringman, Seattle Times. ("Fast lane meets slow lane on Bothell's new 'multiway").

With regard to bond funding, even in bad economic times, parks-related bond initiatives pass overwhelming in most jurisdictions, including Baltimore County. And this idea of making roadways a type of "linear park" increases the likelihood of a successful referendum.

The model that I suggested was based on Seattle's Bridging the Gap initiative which is now called Move Seattle. It used a levy passed by referendum and other funds to implement a variety of mobility and public space improvements, from road repaving to Safe Routes to Schools initiatives.

Another example is the "Metropolitan Area Projects program in Oklahoma City, which funds various high level capital projects, along the lines of what I call transformational projects action plans ("Downtown Edmonton cultural facilities development as an example of "Transformational Projects Action Planning"").

Street sign topper, Portland, Oregon. Wikipedia photo. My idea was to have a "Baltimore County Signature Street" sign topper on street signs for the newly defined Signature Streets sustainable mobility network.

Elected officials and stakeholders need to think much bigger about mobility infrastructure. Elected officials especially need to understand that the mobility system--roads primarily but sidewalks and transit infrastructure too--defines the image and position of the community. They need to take responsibility for managing and shaping that system.

When I wrote a couple of commercial district revitalization framework plans for Brunswick, Georgia and Cambridge, Maryland in 2008 and 2009, I made the point that:

... elected officials need to take their responsibilities as stewards and managers of a community's image very seriously:

Just as the study team believes that “we are all destination managers now,” elected and appointed officials in particular and in association with other community stakeholders serve as a community’s “brand managers”—whether or not they choose to think of their roles in this manner.

That means that decision-making on land use and zoning, business issues, infrastructure development (roads, sewers, water, utilities, transit), technology (broadband Internet, etc.) and quality of place factors (arts, culture, historic preservation and heritage, education, public schools and libraries, urban design, etc.) must be consistent and focused on making the right decisions, the decisions that collectively achieve and support the realization of the community’s desired vision and positioning.

Another way to think about this is in terms of branding. How people perceive and think about a community has to do with its reputation and other qualities. Decisions either add or subtract value from the brand, depending on the results.

Typically, elected officials don't think about the sum total of their decisions and outcomes in this way.

Which is why many decisions made by elected officials end up having negative consequences.

Labels: civic architecture, micromobility, roads, sustainable mobility platform, transportation infrastructure, transportation planning, urban design/placemaking

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home