The house as a haven and refuge, nimbyism, and urban-ness

Adams Morgan Day--a fun festival serving the city, or an abomination, an unreasonable sacrifice provided to the city on the part of Adams-Morgan residents?

I am not quite finished reading Cameron Logan's dissertation on planning in DC, covering the period from 1950-1990, and mostly dealing with the role of historic preservation in the city's planning processes, and how it organized neighborhood stabilization in response to expansion of downtown northward (Dupont Circle) and the U.S. Capitol Complex (Capitol Hill), and how developers and real estate interests learned to respond and reshape the debate in the 1980s, under a particularly hospitable political regime (Marion Barry).

(I will be writing more about it, once I finish it in a couple days.)

One of the interesting things that I am pondering is how for many people involved in the neighborhood preservation movement, there wasn't an interest in creating the kind of urban vitality of mixed use and activities at different times of the day that is discussed in say, Death and Life of the Great American City, the Jane Jacobs classic.

This could have been because of the development of more nucleated families, and a more self-involved household focus, rather than a more externally connected, community-neighborhood involved perspective. Clare Cooper Marcus, in "The House as a Symbol of Self" says that for the most part, people desire a house form that is "separate, unique, private and protected" while Delores Hayden writes in Redesigning the American Dream about the haven strategy, where the house--home--serves as a haven, a refuge, from the exploitation and competition of the mass market and the industrial world.

In the neighborhood preservation movement in DC (as opposed to the preservation movement focused on downtown buildings), for the most part people were focused on saving residential building stock, and perhaps because often preservation was a protective response to encroachment by commercial real estate developments, they were less inclined to be interested in or supportive of retail and other commercial activities.

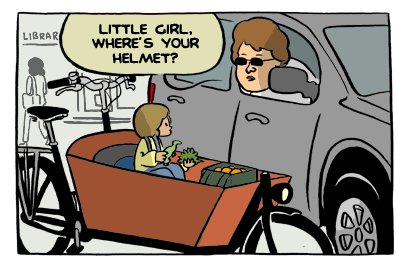

Neighborhood commercial district cartoon, Peter Wallace.

Logan describes some discussions of neighborhood vitality including local retail in a positive light. Interestingly, these perspectives came from people with commercial interests, a real estate business proprietor key to resuscitation of the Capitol Hill neighborhood (Barbara Held), and from the mid-1970s editor of the community newspaper The Intowner, which still serves DC's "mid-city" neighborhoods.

I wonder if there really is a widespread commitment to urban-ness, mixed use, variety of activities, and vitality in the center city? Maybe there isn't?

I ask this question because on the ANC6A listserv, there is a negative thread about the recent National Marathon, which involved, besides running, the closing of a number of streets in Capitol Hill for a goodly part of one day. (Judging by some of the postings when the Marathon happened, one of the problems is inadequate training for the people, including police, working the Marathon, because for the most part when queried, they were unable to provide alternate route information.) One of the respondees wrote (edited):

There is an ever increasing number of races and other such events that burden the Capitol Hill community, often drawing large crowds and buses, and forcing traffic and parking restrictions. David has a point that it's time that other sections of the City share the wealth and/or the burdens.

Granted, I don't live in that area now. But I tend to think of street closures as temporary events that can be dealt with, minor annoyances that can be responded to with "work-arounds," but also part of the "ballet" of civic life and urban vitality.

As a resident in my neighborhood, I give up some things on occasion (I can hear loudspeakers for sporting events at Coolidge High School even though I live three blocks away; the pool is closed on occasion for swim meets; the occasional train whistle on the Metropolitan Branch railroad line; etc.), in favor of serving others, and I expect that "what goes around, comes around" -- that I get things back too, when I go to activities in other neighborhoods, such as Adams-Morgan Day, which can cause hardships for people in that neighborhood on that day, even as people like me reap the benefits.

Given that I have been pondering civic engagement and planning issues for the past few days in the context of Cameron's dissertation, I have been wondering if the idea of what it means to live urbanistically is a construct also, a construct that few residents really have an interest in or support generally, whether or not they face specific development threats from time to time, and utilize preservation policy or other neighborhood or community organizing strategies as a way to respond?

Maybe nimbyism is merely a smaller piece of a much larger problem?

Interestingly, while discussions of diversity talk about the value of different perspectives, research by people like Robert Putnam finds more civic involvement in more homogeneous communities.

I talked with Anwar Saleem of H Street Main Street about doing a session at next year's Main Street conference about the "difficulties" of doing commercial district and community revitalization activities in "hetereogeneous" communities. It's very difficult. That's what people have spent the last ten years learning on H Street. Sadly, the Main Street commercial district revitalization model doesn't adequately prepare volunteers for this reality.

Labels: civic engagement, historic preservation, urban design/placemaking, urban vs. suburban